It is about 9.30 on a balmy night in Kolkata. I am standing under a busy flyover. There are people sitting, chatting or reading newspapers. And here and there are small groups of men, squatting on the metal railings, huddled over chessboards.

This flyover space is an informal chess club of sorts. Men come here in the evening after work, play a few rounds, oblivious to the constant, heavy traffic and noise. It would be unusual to find women among these groups — it’s not the done thing, probably because these are late evening sessions, and most women have to hurry back home to cook.

This is also because women generally prefer not to (or are not supposed to) hang around at public spaces this late. One of the diktats issued by the city police after the infamous Kolkata gang rape incident (subsequently known as the Park Street rape) was to place a curfew as a safety measure — don’t be out late, dress decently, thus reiterating the misconception that the onus of protecting oneself from assault or harassment lies solely on the woman.

However, this night under the flyover is different. A group of about 20 women and a few young men are singing, laughing, playing Ludo. They attract curious glances from the traditional inhabitants of this space as well as passersby. As the evening progresses, more women arrive. Of them is handing out visiting cards — “I am starting a self-defence class for women,” she says. “Do come.”

Quite a few of them are college students, some are older. A couple of them enter into a conversation with the chess players.

“Shouldn’t you be going home? It’s getting late, avoid any trouble,” a man tells them.

“When are you going home,” a girl asks.

“Oh, later. But that’s different,” the man answers, laughing.

“Well, we want to be here, we want to be seen. You can’t expect women to be caged up at home for their ‘safety’,” a young girl argues.

The man shrugs and says, “You are right, but what can be done? It is for your own good that I am saying this.”

And the argument continues.

It is 11pm, and the men have gone. The group of women is still around. They write slogans on the now empty road — “Raat aamar, shohor aamar” (The night is mine, the city is mine).

This is one of the many interventions and campaigns by Kolkata’s Take Back The Night, a diverse group of citizens who aim to make city spaces safer for women, and other vulnerable groups. The group has held several meet-ups and interventions such as boarding public transport buses at night and talking to passengers and drivers about the issue.

TBTN gatherings are one of the several citizen-centric campaigns that have emerged in the recent past in India to combat patriarchal notions of safety, women in public spaces and incidents of harassment and abuse. In a scenario in which the state has done very little (in fact, many politicians and government officials say the most regressive things about women with impunity), this makes sense.

One of the earliest campaigns by women to reclaim space was Why Loiter?, an online and offline movement across Indian cities that reiterated the importance of women’s need to visibly “loiter about” in public spaces. It calls upon women to “make a statement ... to be in public space without purpose”.

Then there is Bengaluru-based Blank Noise which has implemented several interactive awareness-raising campaigns about women’s experience on the street. For instance, the “I Never Asked For It” campaign asked women to submit photos of the clothing they were wearing when they were harassed. The aim was to demolish the notion that only certain kinds of dresses invite harassment, The photos were sometimes accompanied by the story of what happened during the incident.

Another project, Meet to Sleep, asked women to meet up and sleep in parks, something men do frequently in India. Their FB page was inundated with photos by women in supine positions with quotes such as “Meeting to sleep reinforced for me the bliss of being oblivious in using public spaces. Being in a group helped me let my guard down and enjoy that beautiful afternoon without worrying about the integrity of my personal space, and the absence of that fear helped me see how it’s up to me to place my trust in the environment and use it without constraint — most of my apprehensions stemmed from being brought up thinking being very cautious will help prevent some supposedly inevitable injury. I have subsequently napped by myself in the park and it was great!”

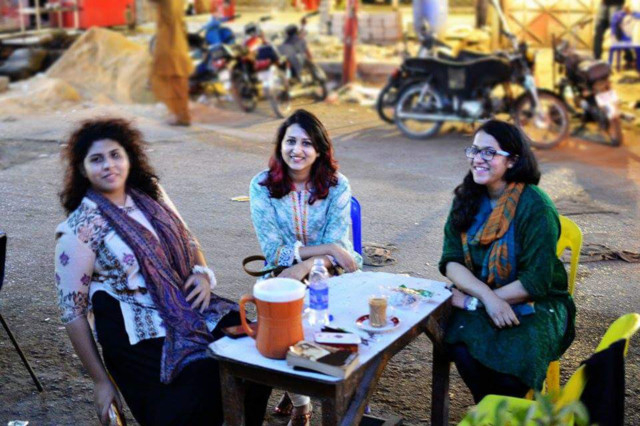

Across the border, in Pakistan, women are claiming dhabas (roadside eateries) via a unique hashtag, #girlsatdhabas. The Tumblr blog Girls at Dhabas has been trending on social media, and coming as it does from a largely conservative country such as Pakistan, it has become a much-talked about topic. The blog features pictures of women hanging out, drinking chai (tea), eating, reading and just generally chilling at dhabas.

Dhabas are known as male-dominated spaces. “They represent a break of sorts from the daily grind without having to necessarily buy the experience. It is similar to how people might sit at streetside coffee shops or public spaces to hang out, have a cup of coffee or chat,” says Sadia Khatri, one of the founders of Girls At Dhabas.

It all began with the girls venturing out in city spaces, when Khatri started documenting dhabas through photos on her blog. She did not think that her hashtag, #girlsatdhabas, added to photos posted on Facebook from her trip to local tea shops would mean anything. But the photos struck a chord and led to discussions about women at dhabas and how they are a rarity.

The group set up a Tumblr page to see if other women would contribute. A Facebook page followed soon after. The posts sparked national and international conversations about women’s freedom to move around as they please. Girls at Dhabas wasn’t necessarily a preconceived idea and its growth has been organic. The hashtag found resonance after Khatri started documenting photos at dhabas. It has now come to symbolise a lot more in terms of the conversation around reimagining public spaces for women in Pakistan.

The photographs are an eye-opener — from jeans-clad women sitting on a charpoy surrounded by men at a truck stop somewhere on Karachi’s outskirts to women in salwar kameez seated around plastic tables with chai cups, smiling to the camera, some riding on rickshaws, motorcycles or cycling. A spin off #GirlsPlayingStreetCricket has women playing the game on streets. Many images are accompanied with messages.

The project’s received attention all over the world. “A few months ago, some postgrad students in another part of the world e-mailed us. They were doing a project on urban spaces in Karachi and wanted some perspective on how to view street norms from the context of gender. We had some fantastic conversations over the past few months, and their project conversely has given us new food for thought,” says Khatri.

The women at Girls At Dhabas come from varying socioeconomic backgrounds across Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad. They manage the page, plan events and co-ordinate with various groups to raise some noise about women’s participation in public spaces. They put in time and as when they can — and work across fields. Some of them are working full-time, some are in undergrad or grad school, one is a journalist, one filmmaker, one is a teacher, several work with NGOs and research collectives, and one is a graphic designer.

The group says they have found a lot of strength through movements in India such as Why Loiter?, Blank Noise and Feminism in India.

“It’s reassuring to know that this work isn’t being done in isolation. Particularly, it’s encouraging to know that there is a history and context to gender dynamics in public spaces in South Asia that many folks are trying to battle against across fields,” says Khatri.

Since starting the group, they have connected with feminists, rights workers, NGOs, anthropologists, designers, businesswomen and social workers. “It is honestly incredible and a relief to know that there is a bigger support group and resource base than we realised, that so much more can be done when we do it together,” says Khatri.

Even in terms of situating themselves as a group, the book “Why Loiter? Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets” turned out to be an essential resource. “Natasha [Ansari] and I talk about this often ... Shilpa [Phadke], Sameera [Khan] and Shilpa [Ranade] had taken all of our thoughts and frustrations and articulated them with logic, reason and relevance,” says Khatri. “I think we understood a lot of our own work personally better, too. And it certainly brought up new questions. The intersection of class and gender is something that often comes up in our conversations and interactions with people [both online and offline], and the book is a fantastic study of class and gender dynamics in Mumbai, so there are entire chapters we can draw from.”

Soon after the hashtag got a lot of attention, Why Loiter? had reached out to them. The groups have stayed in touch, trying to implement cross-border collaborations to get the tea shacks of India connect to the dhabas of Pakistan. Last December, Girls at Dhabas hosted #WhyLoiter on the same days as organised in India. “Why Loiter? has also made us think about the process of spreading something such as this. We are definitely taking a lot of cues from them,” says Khatri.

Audience-wise, Khatri says men are probably the biggest critics of #girlsatdhabas. “There is the popular argument based on religion, where we are told our narrative doesn’t fit into the one Islam has prescribed for women. Then there is the quick dismissal by elite, progressive, ‘secular’ men who feel threatened and can’t figure out why women want to sit at a dhaba and have a chai, why it is even an issue.”

She admits that they have a long way to go before any of those mindsets can be eradicated or addressed. “We are trying to ‘educate’ by example and personal stories, since a series of online and offline arguments have convinced us that getting into a ‘debate’ gets the conversation nowhere,” says Khatri.

Anuradha Sengupta is a writer based in Mumbai.