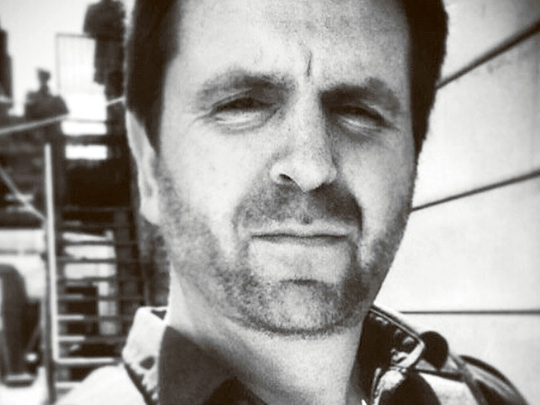

In his 20-year career as a journalist, Iain Overton has worked in more than 80 countries. From troubled hotspots such as Iraq, Somalia and Colombia to places such as Brazil and Turkey — this is a man who has seen the world.

So when Overton decided to write his first book, covering the contentious topic of guns, it was perhaps not a surprise that he wanted it to be “international”. Specifically, he didn’t want to cover only one country that tends to dominate the debate on guns: “I didn’t want it to be America, America, America!” he tells Weekend Review. “Because most people — when they talk of gun control and guns — immediately talk of America.”

I met Overton inside a busy café in London. Sitting at a table next to the window, there is a clear view of the street outside. Pedestrians walk by enjoying the cool summer breeze. The barista occasionally comes to collect empty cups and clean the tables as I listen to Overton.

“I have seen guns outside America causing untold harm and yet very little is spoken about it,” he says. “People don’t write about inter-country smuggling between Burundi and Congo. They don’t talk about Liberian guns in the hands of child soldiers. They don’t talk about the proliferation of American guns coming south of the border into Central America and Mexico. And really my book is an attempt to globalise the debate around guns, to place America within that debate.”

The fact is the United States does not hold a monopoly over gun crime. “The worst massacre in the world happened in Norway. The second worst massacre happened in South Korea, not America.”

Overton’s book investigates gun culture in 25 countries. As director of policy and investigations at Action on Armed Violence (AOAV), a charity that works to reduce harm and rebuild the lives affected by armed violence, he is in a unique position to write on the issue. Part of Overton’s work involves travelling to different countries that have been affected by violence. “I am off to Lebanon in a couple of weeks to look at the legacy of the Israeli bombing of Beirut,” he says. “I probably will be going to Ukraine to look at the use of explosive weapons there.”

“Gun Baby Gun” was born out of Overton’s quest to answer the question of why violence perpetuated by certain weapons gets more attention than others. He says: “If somebody is beheaded with a knife people go ‘oh my god’. Somebody who is blown up by a suicide bomber, they say, ‘this is how they die’. But the weapon doesn’t become an issue. And that intrigued me.”

Overton began to dig around and remembered some of his own personal encounters. “I have been held at gunpoint a number of times,” he says.

He worked on the book throughout 2014. A lot of writing was done while commuting on the Underground. “It is strange. I often work in places that are very noisy because it makes me focus,” he says. “If it is very quiet, I sort of end up daydreaming.” Some of the book is a retelling of Overton’s past journalistic investigations. But he also travelled to countries such as Ukraine and Turkey specifically for the book.

One of the places he visited was Israel. “The most militarised nation on Earth,” he says. At the airport in Tel Aviv, Overton remembers being questioned for five hours. “I had previously been to Pakistan to interview a man who used a gun for self-protection,” he says. “They wanted to know why I was in Pakistan, why I had been to Nigeria, why I had been to this country and that country. I think they were trying to work out what I was, if I was a troublemaker or not. I guess as a journalist you have to be a troublemaker.”

For visitors to Israel, such interrogation is nothing new. “I think that is fairly typical actually,” he says. “If it’s a journalist, or anyone with Arabic heritage, visiting, they are interrogated. Unless you are writing for certain American newspapers, you are going to be interrogated.”

He tried to get an interview with the Israeli army but was refused. However he did manage to interview a female sniper who had been a trainer to the army. “One of the problems of the entire debate is that the Palestinians are very open and friendly and wanting to give you an interview,” he says. “But the Israeli army rarely gives you an interview. I think it is very difficult to get a really balanced view because you are not allowed to speak to anyone on the Israeli side. So then the immediate response you get from Israelis or American Jewish communities is that you are somehow being anti-Semitic for commenting on the levels of violence. This is nothing about religion. It is purely about human rights.”

He crossed over into Palestine where he met a boy aged about 16 at a hospital. The boy had been shot by an Israeli sniper for hurling stones, but it was not in the news. “It struck me how intriguing that was. In Europe, if a young boy is shot by another soldier, it will be front-page news. If this happened in America, everyone would know about it. We have very dislocated priorities on death.”

In Israel, he feels, there is an “overstated aggressive response” to anything considered a threat. “I think you should be justifiably angry that a 16-year-old was shot. I did say in the book that it is impossible to know all the angles of the story. But the Israeli sniper wouldn’t give me an interview.” He feels that in many ways, Israel has adopted at least some of the approaches to guns and national safety that the US has.

While the impact of the US gun policy is much debated, less widely discussed is its impact on foreign policy. “They think that by taking lots of guns to Iraq or Afghanistan, they would win the war, win democracy, win freedom. But when they sent the guns to Iraq and Afghanistan, [they] obviously [did not account for] corruption in these countries and incompetency of the Americans. I mean a huge number of guns just went missing.”

In 2014, it was reported that 43 per cent of the 747,000 weapons given to the Afghan military by the US Defence Department could not be accounted for. Similarly in Iraq, the Pentagon lost track of 190,000 rifles and pistols given to Iraqi forces.

“Many of those guns have ended up fuelling terrorism in the region. People look for M16s in places such as Iraq and Afghanistan but the truth is the Americans also equipped Afghan and Iraqi forces with AK-47s. So we will never know what the origin of Isis’s [Daesh, the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant] guns are for instance. Or Al Qaida’s.”

The negative impact of US gun policy is also felt by neighbouring countries. When Bill Clinton was the president, he issued a 10-year ban on the sale of semi-automatics. “Over those 10 years, the number of homicides using that type of weaponry in Mexico sort of hit a plateau,” says Overton. “However, the ban was later lifted in states such as Arizona, but not in California. South of the border of Texas in Arizona, there was a rise in murders, which wasn’t the case in south of California.”

There appears to be a direct correlation between looser American gun laws and a rise in Mexican deaths. “There is only one gun shop in Mexico. There are more federally licensed gun dealers in the US than there are McDonald’s [restaurants].”

Overton was the founding editor and former head of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism. Among other projects, he worked with Julian Assange on the famous Iraq war leaks.

“Wikileaks is a good example of the hidden use of guns,” he says. “For instance, there was a huge number of civilians shot by trigger-happy American soldiers at checkpoints in Iraq. We found human rights abuses by American guns, by soldiers. It really struck me that once you start a conflict, soldiers basically have a government-sanctioned right to murder people and there is very little accountability.”

I ask Overton if there was anything that particularly shocked him while working on the book. He mentions the issue of guns and suicide. “There are around 10,000 homicides in the US every year,” he says. “There are around 20,000 suicides involving guns every year. Gun homicides versus gun suicides.”

As compared to taking pills to kill oneself, the probability of using a gun is a lot higher. “They did some surveys and quite a significant minority of people had only thought about taking their life five minute before. There is a moment of despair, a moment of crisis turns into a lethal moment.”

Overton has directed documentaries for the BBC, ITN and Al Jazeera. His work has won a Peabody Award, two Amnesty Awards and a Bafta Scotland. Since the book came out, Overton has been flooded with calls from journalists. He is also increasingly being asked to speak at literary festivals about gun violence.

Part of the appeal of the book is that a lot of writing out there on guns is academic while Overton’s style makes it more accessible to a general readership. And the book’s title too plays on words. “In some ways it was meant to be slightly ironic. I mean there is ‘Run Baby Run’ and there is ‘Gone Baby Gone’,” he says.

Philip Alpers, founding director of Gunpolicy.org and a leading voice on armed violence reduction, has described “Gun Baby Gun” as the “best” book written on the global overview of guns and their effects. The book has also been praised by award-winning journalist Jon Snow as a “brilliantly researched journey”.

However, not all feedback has been encouraging. “I have been called everything under the sun on Twitter by American gun advocates. But my point really is it is not a book about America. It is kind of self-centred for every American to think the moment you talk about guns you are talking about them.”

One of the challenges that remain is there’s big money behind the US gun lobby. “The very point of it is that the gun lobby is funded by a highly profitable industry,” he says. “There is no highly profitable industry that underpins the gun control lobby, nobody is making money out of gun control. Lots of people make money out of the sale of guns.”

Syed Hamad Ali is a writer based in London.