Cicadas, every Japanese schoolchild knows, lie underground for years before rising to the earth’s surface in summer. They climb up the nearest tree, where they cast off their shells and start their short second lives. During their few days among us, they mate, fly and cry. They cry until their bodies are found on the ground, twitching in their last moments, or on their backs with their legs pointing upward.

Chieko Ito hated the din they made. They had just started shrieking, as they always did in early summer, and the noise would keep getting louder in the weeks to come, invading her third-floor apartment, making any kind of silence impossible. As one species of cicadas quieted down, another’s distinct cry would take over. Then, as the insects peaked in numbers, showers of dead and dying cicadas would rain down on her enormous housing complex, stopping only with the end of summer itself.

It was the afternoon of her 91st birthday, and unusually hot, part of a heat wave that had community leaders worried. Elderly volunteers had been winding through the labyrinth of footpaths, distributing leaflets on the dangers of heatstroke to the many hundreds of residents like Ito who lived alone in 171 nearly identical white buildings. With no families or visitors to speak of, many older tenants spent weeks or months cocooned in their small apartments, offering little hint of their existence to the world outside their doors. And each year, some of them died without anyone knowing, only to be discovered after their neighbours caught the smell.

The first time it happened, or at least the first time it drew national attention, the corpse of a 69-year-old man living near Ito had been lying on the floor for three years, without anyone noticing his absence. His monthly rent and utilities had been withdrawn automatically from his bank account. Finally, after his savings were depleted in 2000, the authorities came to the apartment and found his skeleton near the kitchen, its flesh picked clean by maggots and beetles, just a few feet from his next-door neighbours.

The huge government apartment complex where Ito has lived for nearly 60 years — one of the biggest in Japan, a monument to the nation’s postwar baby boom and aspirations for a modern, US way of life — suddenly became known for something else entirely: the “lonely deaths” of the world’s most rapidly ageing society.

Summer was the most dangerous season for these deaths, and Ito wasn’t taking any chances. Birthday or not, she knew that no one would call, drop a note or stop by to check on her. Born in the last year of the reign of Emperor Taisho, she never expected to live this long. One by one, family and friends had vanished or grown feeble. Ghosts, of the living and dead, now dwelled all around her in the scores of uniform buildings she and her husband had rushed to in 1960, when all of Japan seemed young.

She had been lonely every day for the past quarter of a century, she said, ever since her daughter and husband had died of cancer, three months apart. Ito still had a stepdaughter, but they had grown apart over the decades, exchanging New Year’s cards or occasional greetings on holidays.

So Ito asked a neighbour in the opposite building for a favour. Could she, once a day, look across the greenery separating their apartments and gaze up at Ito’s window?

Every evening around 6pm, before retiring for the night, Ito closed the paper screen in the window. Then in the morning, after her alarm woke her at 5.40am, she slid the screen back open.

“If it’s closed,” Ito told her neighbour, “it means I’ve died.”

Ito felt reassured when the neighbour agreed, so she began sending the woman gifts of pears every summer to occasionally glance her way.

If her neighbour happened to notice the paper screen in daylight, the woman could promptly alert the authorities. Everything else had been thought out and taken care of in advance. On her 90th birthday, Ito had filled out an “ending note” that organised her final affairs. The notes, which have become popular in Japan, help ensure a clean, orderly death. Ito had also given away the tablets from the family’s Buddhist altar — the miniature headstones considered so precious that many Japanese would scoop them up before running out of a house on fire.

So many things in her apartment now reminded her of the dead. There were the paperbacks, hundreds of them jammed onto shelves, that her dying husband had told her to throw away after reading. The finely carved chest of drawers, which her daughter had carted away after getting married, sat there, too, returned decades ago when the young woman died. Tucked inside a cabinet were the books that Ito had written herself, including a dry but exhaustive two-volume book about her life in the housing complex and a 224-page autobiography, all finished in a final burst of activity.

The heat soon started taking its toll. By midsummer, two bodies were discovered in the complex — victims, it seemed, of the early heat wave. The first death occurred in Ito’s section, where a woman detected the smell from the apartment below. Initially, she thought somebody had gotten a delivery of dried fish called kusaya. Then the stench intensified, especially on the balcony where she hung her laundry. None of the dead man’s neighbours knew him, although he had lived there for years. He was 67.

The second man’s body was found two days later. Again, the smell had become so intense that it had kept his next-door neighbour awake for three nights. The man was elderly, had lived there for years, and chatted about the cherry blossoms with his neighbours, but they didn’t know his name. The inside of his apartment, visible through a small ventilation window, was covered in trash. Green bottle flies hovered around the vent.

The building management tried to contain the smell, taping over every crevice — the edges of the men’s front doors, their letter flaps, even the locks. It was futile. The stench seeped out, filling hallways, stairways and homes.

Ito kept busy, trying not to think about it. She took long walks outside the complex, which stretches across a Tokyo suburb for more than a mile, spreading out in the shape of a giant fan. She kept track of her steps on her cellphone, spent an hour every morning writing Buddhist sutras to her daughter and husband, and helped keep local forests clean with a volunteer group.

Every month, she attended the lunches that residents organised to keep the isolation at bay and reduce the risk of lonely deaths. At the gatherings, she had settled into a routine, always sitting at a table across from a man with wobbly legs and a big appetite, Yoshikazu Kinoshita. The two could hardly have been more different — her days were organised to the minute; he got out of bed only when he felt like it. But their conversations, which some might have dismissed as small talk, had acquired deep meaning.

“That’s the way I manage,” she said of her activities.

She spoke rapidly, in long sentences, with an unusual directness for someone of her generation. Even in uncomfortable moments, she never sought refuge in the vagueness of the Japanese language. For the rare occasions that words failed her, she kept voluminous proof of the life she had lived, cataloged exhaustively by year and subject. The photo books in her apartment were filled with black-and-white images of young families like hers. And bound in yellow covers, with titles in Ito’s elegant calligraphy, were the books she had written, including the two-volume collection on her life in the housing complex: Tokiwadaira.

In the 1960s, the Japanese government built huge housing developments outside Tokyo and other cities, each holding thousands of young “salarymen” entrusted with rebuilding Japan’s postwar economy. The complexes — sprawling collections of buildings called danchi — introduced Japan to a Western structure of life centred on the nuclear family, breaking from the traditional multigenerational homes. The new apartments, seen as essential to Japan’s rebirth, had strict requirements. The monthly wages of tenants in Tokiwadaira had to be at least 5.5 times the rent, ensuring that only the most successful people got in.

Ito’s husband, Eizo, worked at a top advertising agency. But competition to enter one of the danchi was so fierce that the couple had given up after 13 tries. Then a relative secretly submitted an application in their name for a place still under construction, on farmland an hour east of Tokyo.

The Itos arrived in mid-December 1960, on the first day that tenants were allowed in. It was a clear day, full of promise, with Mount Fuji visible in the distance from their third-floor balcony. Her 4-year-old stepdaughter, Ito wrote in her autobiography, was “so happy that she ran around the apartment, drawing a complaint from their second-floor neighbour.”

After Ito gave birth to a daughter a couple of years later, everything was settled. Her husband rode the packed train six days a week to Tokyo. She taught at a nursery school inside the complex, in charge of the Tulip Group. The danchi’s population of children swelled, just as it did all over Japan. In a few years, there were so many children that they collectively became known as Japan’s Second Baby Boom generation.

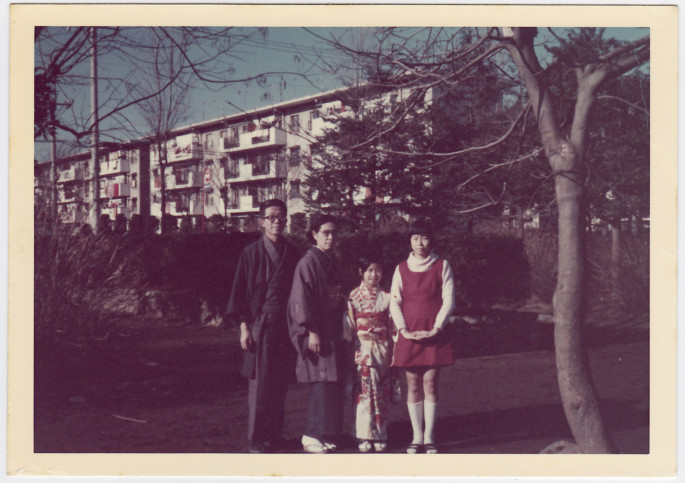

Every New Year, the family put on their kimonos for photos. They also took part in the annual sports days, a ritual of Japanese life in which children and parents compete in races and other events. In the summer, Ito took her daughters to one of the danchi’s wading pools. In her photos, the pool is always full of water, always full of young mothers in modest one-piece bathing suits, always full of children.

Ito used to stand at her window, the one with the paper screen, and look down at the playground and sandboxes below. The children of the nearby buildings played there together, their shouts loudest during the summer. Now, no one played there. The children had mostly vanished, their jubilant cries replaced by the frequent annoying sirens of ambulances.

In her book, Ito broke her life in the danchi into two distinct parts. The first begins with her wedding and ends 32 years later with the deaths of her husband and daughter.

She gave the impression that her life — her true life — had ended with theirs, especially her daughter, of whom she often spoke in the present tense. Sometimes she would tell a joke or show a flash of anger at the mention of her daughter’s death. More often, she stared straight ahead.

Part two — subtitled “My Second Life” — focuses on friends, trips and goings on around the housing complex. Old friendships are renewed and new ones are made, although Ito outlives them all.

As the weeks passed and the cicadas’ incessant cries became the backdrop to every conversation, Ito ultimately concluded that she had started writing to break the solitude, so she wouldn’t forget. “Even the unhappy events,” she said. “Otherwise, everything is lost forever.”

One of Ito’s closest friends moved in after becoming a widow. They ran into each other at the local supermarket’s frozen foods section, so glad for the company that neither complained about the cold. “After that we became inseparable — that’s just the way I am,” Ito said.

Years passed. The woman died, as did other friends, inside and outside the danchi. Her sister developed dementia. A brother became homebound. Even a younger brother now had trouble walking.

“I’ve been lonely for 25 years,” she said. “They’re the ones to blame for dying. I’m angry.”

At the monthly lunch for tenants who live alone, Ito, a light eater, got into the habit of giving her tablemate, Kinoshita, half of her meal before she started. After learning that he liked reading, she lent him a few books. He began lending her some, and included some chocolate.

Once, he asked her to come to his place to retrieve a book.

“That’s when I found out that his place was full of garbage.”

Kinoshita was 83. His legs had grown weak. He used a “silver chair” that he rolled in front of him to steady himself. He left his apartment perhaps once a week.

After Ito saw the state of his apartment, she alerted community leaders. Men who lived alone in the danchi, weakened by age and infirmity in apartments like that, were the most vulnerable. She learned that volunteers were already keeping an eye on him.

His company, I Love Industry, which worked as a subcontractor on underground construction projects — the “tail of a mouse,” he said — had ridden the country’s construction boom from the 1960s through the 1990s until public works contracts dried up.

Yet he had also enjoyed a moment of glory, one that he clung to the way Ito clung to the Tokiwadaira in her books. During the construction of the Channel Tunnel, he had supplied a major contractor, Kawasaki Heavy Industries, with equipment — a reel for a hose — to help bore under the Strait of Dover.

From his foray in Europe, he had brought back a habit of sprinkling some French words into his speech, on top of the broken English he had picked up decades earlier from a college friend.

“All over Paris, I kept hearing, Merci madame,” he said. “I couldn’t wait to go back to Tokyo and say, Merci madame.”

His friendship with “Madame Ito” gave him energy, although she was the one who did most of the talking. “She’s very assertive, to the point where I can’t get a word in,” he said.

As it had for decades, Tokiwadaira held its Bon dance during the last weekend of August. The late summer evenings were already noticeably cooler.

A few days beforehand, Ito got a phone call from her lunch companion, Kinoshita. After being cooped up in his apartment for what seemed like years, he couldn’t wait to go to the dance and checked with Madame Ito to make sure of the date. She had stopped going decades ago, after her children grew up. When the danchi swelled with children, the dance was held in a large park, not in the small plaza where it was now taking place.

People began gathering after sunset. They danced in circles around a stage in the middle of the plaza, illuminated by hanging red and white lanterns.

Kinoshita slowly pushed his silver chair through the crowd, resting on a bench under an elm tree. When introduced to someone new, he simply said, “The only thing I have left is the Eurotunnel.”

It was getting dark. Crickets were singing, the harbingers of autumn in Japan. Deeper into the danchi, toward Ito’s apartment, the door of the dead man was still taped over, the smell refusing to disappear. Deeper still, past the deserted pool and the playground where her daughter used to play, Ito’s window was visible, faintly, in the night.

The paper screen was closed, waiting for her to slide it back open in the morning.

–New York Times News Service