I was 11 when I read my first romance novel. It was Where Eagles Dare, by Alistair MacLean. I was home from school sick with something that kept me snuffling under a snowdrift of rumpled tissues, and had read every book on my shelf. In my older brother’s room, the only novel I could find was this, one of MacLean’s Second World War thrillers.

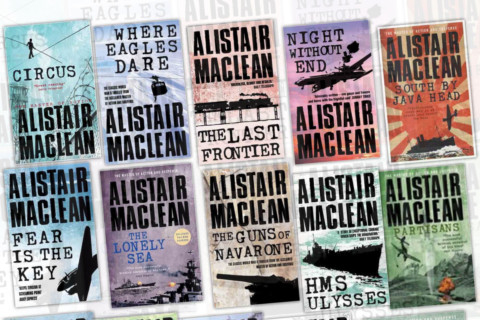

I read his book in an afternoon, transported to Schloss Adler, an impregnable Nazi fortress in the Bavarian Alps where an American general was held captive. As soon as the daring rescue was done, I ransacked my brother’s room and discovered an entire cache of Alistair MacLean. In between bouts of wheezing, I devoured one after the other: South by Java Head, When Eight Bells Toll, The Guns of Navarone, Night Without End, Ice Station Zebra and, my favorite, The Golden Rendezvous.

Years later, I understood that these were in fact romance novels for boys, which means very little romance and lots of danger, complicated weaponry and battle-forged camaraderie. Historical romances are known as “bodice-rippers.” The only silk to be found in an Alistair MacLean novel is on a parachute.

But I had never read a real romance novel — I hadn’t yet discovered Jane Austen or Georgette Heyer. So these action thrillers were the first books I read that filled my head with fantasies of love and courtship. I was like Titania, who under Puck’s spell in A Midsummer Night’s Dream falls in love with the first person she sees. I was so captivated it didn’t matter that the heroine was secondary or that the wooing was perfunctory and mostly took place under gunfire while climbing the cliffs of a Greek island or escaping the Japanese in a lifeboat in the South China Sea.

We lived in Paris and I went to a French all girl’s school where teachers limited our reading to a children’s imprint called La Bibliotheque Rose. I couldn’t share my MacLean fixation with my best friend because she would only read novels on the prescribed pink list.

So mine was a lonely passion, deepened in a way by the solitary communion with bosuns, saboteurs and germ warfare specialists. These heroes were all loners, strong and mostly silent. They didn’t chase women or even miss them. Sometimes, in the middle of a covert operation or a terrorist heist, a beautiful girl would come along and briefly win the hero’s heart, before he had to shove his feelings back in the glove compartment, pick up a marlin spike and 1,000 rounds of ammunition and save the world — while making the occasional wisecrack.

And that is what made The Golden Rendezvous my favorite. It was written in 1962 and set aboard a luxury freighter that is hijacked by pirates smuggling a tactical nuclear weapon. The plot was suspenseful but what I liked best was the sardonic first-person narration by its hero, First Officer John Carter.

“A hand touched my arm,” Carter says. “Captain Bullen again, I thought drearily; it had been at least half an hour since he’d been around last to talk to me about my shortcomings, and then I realised that, whatever the captain’s caprices, wearing Chanel No. 5 wasn’t one of them. This would be Miss Beresford.”

Susan Beresford is of course the love interest: a willowy, auburn-haired heiress whose hauteur and needling humour mask a tender heart. Carter can’t stand her — until he does.

MacLean was Scottish and another thing I intuitively liked was that his heroes were mostly rough-hewed social nobodies formed by the Second World War and not on the playing fields of Eton like James Bond. I didn’t know much about British class snobbery then, but I sided with outsiders.

One of the few MacLean novels I didn’t love was one of his most famous, HMS Ulysses. It was his first and based on his own wartime experiences and it describes the perilous Arctic travails of a British cruiser escorting merchant ships delivering materiel to the Soviet Union. But HMS Ulysses didn’t include a love story, and my attention stumbled over what seemed like endless descriptions of scuppers and fo’c’sles.

Many years later I read another classic about the Arctic convoys: The Cruel Sea, by Nicholas Monsarrat. I was by then old enough to appreciate the brutal cold and endless terror those sailors endured. The Cruel Sea had a pallid romance tucked into a subplot, but that didn’t interest me at all; I just wanted to get back to the men on the ship. I was certain that Monsarrat’s novel was infinitely better than my memory of HMS Ulysses.

Then I recently picked up HMS Ulysses and saw that once again, I was wrong. HMS Ulysses has a different tone than The Cruel Sea, there is more of MacLean’s blend of irreverence and sentimentality, but it is as suspenseful as any of his others and certainly the most moving.

So that course correction reminded me of something I learned when I read Anna Karenina as an adult. When I first speed-read it as a teenager, all I cared about was the heroine’s love affair with Vronsky. Years later, after I had a child of my own, I was mostly consumed by the fact that Anna abandoned her young son for her lover.

Not too long ago, I read it again and discovered that I really didn’t care about Anna or Vronsky or their children. I couldn’t wait to see what happened to Levin’s plans for agricultural reform on his estates.

People don’t outgrow romance, but their taste in romance novels can evolve. I still read a lot of war novels and espionage thrillers. But now I don’t really care if he gets the girl. Now that I am all grown up, the real romance is in seeing how the job gets done.

–New York Times News Service