The life of a teen star used to take place in two acts. In the first, they would reach unfathomable heights of fame as an all-singing, all-grinning puppet for Simon Fuller or Mickey Mouse, living out a highly merchandisable bubblegum dream. In the second, once they had turned 18, they would do something messy with their hair and make new songs in an attempt to be seen as grown up and mature.

The play nearly always ended the same way, with the quest for grown-up acceptance feeling hollow, a lack of acceptance from the “real music” establishment, and often with some kind of public breakdown.

Britney Spears’s transition from a teen pop star was fraught with public breakdowns. Image Credit: AP

Ben from A1, Abs from 5ive, Robbie, Britney, Christina, most of the Spice Girls, the Jonas Brothers, the Olsen sisters, various members of S Club juniors and seniors, Hilary Duff, the cast of “High School Musical”: we have seen the same story play out so many times it feels as if we’re rewatching an old film.

Yet in the past year that scenario has been turned on its head. The most inventive music and interesting stories to emerge in pop music have come from former child stars.

In nightclubs from Peckham to Miami, on the covers of style magazines, in academic thinkpieces, it’s been graduates of the Disney Channel, Nickelodeon and talent-show academies who have been fuelling popular culture.

The narrative has changed, a third act added to the story — the one where the child star strikes out as a groundbreaking “artist” in their own right, with the traditionally “cool” music world doubled-up in praise for them.

It’s more than just stars trying or being told to be mature, or growing with their fanbase — their audience has actually shifted. Before, the only adults at these gigs were parents accompanying their kids; now music fans who left their teens behind long ago are baying for tickets, too.

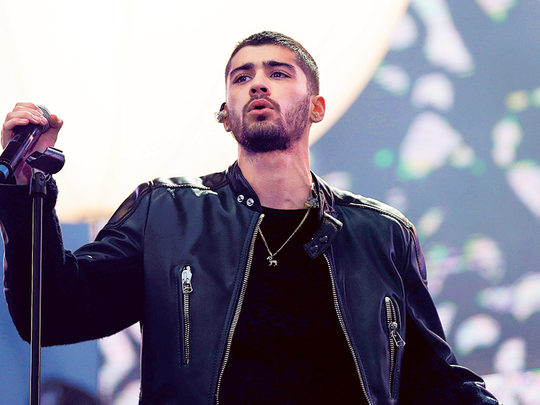

The starkest version of this transformation is happening now, as Zayn Malik, formerly one-fifth of One Direction, released his debut solo album. Not long ago, images of Malik were being emblazoned on to pencil cases as he played out a part in a global tween fantasy. When he dramatically quit 1D last year, however, everything changed.

At first it seemed as if things were heading towards a case of classic post-boyband stress disorder. Malik spent a few months posting embittered tweets (“Remember when you had a life?” he tweeted at former bandmate Louis Tomlinson), dumped his fiancée, Little Mix’s Perrie Edwards, and the tabloids started to run stories about his “meltdown”.

But Malik’s life was not in meltdown. He was holed up in his London mansion to record a solo album (“Mind Of Mine”, which was released on March 25). As opposed to his previous life in 1D, where his every move was masterminded by big teams, Malik wrote all the lyrics to every song himself (which is also presumably why they have titles such as “rEaR vIeW” and “fLoWer”) and recorded half the album with Malay, the architect of Frank Ocean’s edgy R&B sound.

The album’s only featured vocalist is Kehlani, a rising rap and R&B star from California, who herself found fame on “America’s Got Talent” before going it alone and self-releasing a mixtape (it ended up being Grammy nominated). “He’s a genius,” she says, which isn’t exactly the word you might have associated with a manufactured boybander. “He knows exactly what he wants and doesn’t want, and that’s incredibly admirable in an artist. His writing style is very necessary for our generation.”

That “necessary” style is diffuse, a sound that reflects the current trend for pop music that cuts across genre but borrows from Disclosure-style house, R&B and reggae. Its lyrics, meanwhile, incorporate adult themes, unshackled from coy pop insinuation.

That real talk seems to reflect the way that Malik speaks about himself in interviews, too. In a cover story for trendy youth culture magazine the “Fader”, he spoke about being a working-class Muslim from Bradford struggling with his own existence.

He told the interviewer, “I love music and I get tattoos and I make mistakes.” It’s hardly the most rock’n’roll declaration to be made this year, but no parent paying close attention would have saved an issue for their 1D-adoring children. It was a clever, calculated move that certified Malik as a credible pop star in the making.

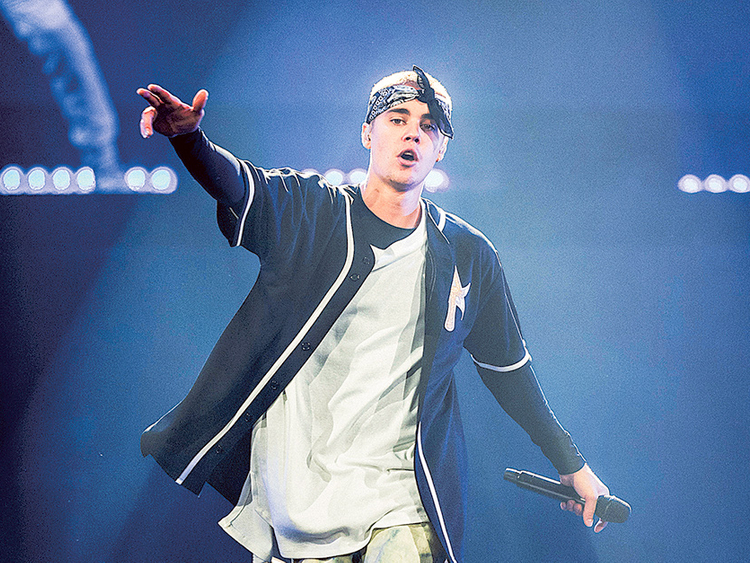

Malik was lucky, in that a blueprint for how to evolve deftly from tween idol to respected star had just been engraved on a gold tablet by Justin Bieber. Bieber’s transformation is probably best summed up by a meme doing the rounds on Instagram.

On one side is the caption “Beliebers 2014” and a photograph of screaming nine-year-old girls in neon pink jumpers, on the other side it says there are “Beliebers 2015” and there is a photo of hard-looking roadmen in puffa jackets and Stone Island on a sofa in a shed.

The gag behind it is that somehow this animated blond twerp went from being a children’s entertainer to the coolest person in music. Now, the same production heads who love buzzy electronic producers such as Hudson Mohawke or Joy Orbison have spent the last six months raving about Bieber’s record “Purpose”. Even Kanye West, not known for doling out superlatives to others, tweeted that “What Do You Mean?” was his favourite track of the year, and Kim Kardashian posted a video on Snapchat of Kanye singing along to it.

“Purpose” was so popular because Bieber did something on it that pop stars almost never do: he didn’t just have hip influences, he struck on a singular new sound. For the album, he worked with EDM producer Skrillex and Grimes collaborator BloodPop to create a digital-tropical lightness of touch, drawing on club culture (cool points!) and Jamaican dancehall’s syncopated rhythms (grinding points!) and with choruses that can bust the charts.

Zane Lowe, who hosts the flagship show on Apple’s radio station Beats 1, is something of a global gatekeeper for what is and isn’t seen as proper music. He would never have played 1D, for example, but he’s been supportive of both Bieber and Malik, interviewing them and premiering their tracks.

“You can dress up pop stardom in a hundred different ways,” he says, of how they’ve gained respect in the music world, “but if an artist wants something more meaningful and lasting, there has to be a willingness to try something different and break up the ‘if it ain’t broke’ philosophy. Justin and Zayn have done that and made smart decisions, working with collaborators who have brought out a different side. They’re evolving as artists.”

For Gabriel Szatan, editor-in-chief at underground music platform Boiler Room, though, their cross-generation popularity comes down to the strength of the songs rather than being recognised as progressive “artists”. It’s all about the nostalgia they conjure from the fans.

“I could over-intellectualise about poptimism storming the gates of techno snobbery,” he says. “But really, bouncing around to [Jack U’s Bieber-featuring hit] ‘Where Are U Now’ with your mates taps directly back into that dumb euphoria of doing the exact same to Rui Da Silva or Chicane as a kid. That’s why Bieber’s clout is growing fast.”

Whether these stars are innovators themselves or just benefiting from working with taste-making producers, brought in by labels to capture a particular sound or style zeitgeist, is a moot point. You can’t imagine Malik or Bieber would have got as far as they have if they’d been left to fend for themselves on GarageBand. But what’s interesting about these stars, over and above technical ability, is their emancipation.

These teen idols were culturally castrated in adolescence, forced to smooth any edges to their personality, so it feels rewarding to hear them make a club banger instead of a faceless bedroom producer you’ve never heard of.

Increasingly, their musical freedom is often coupled with a newfound social liberation: able to say what they want for the first time, former child stars are becoming more and more outspoken on social issues facing young people.

Former Nickelodeon star Ariana Grande is one singer who is using social media to address sexism — as if taking her social media cues from smart stars such as Lorde, she responded to the endless questions asked about who she’s dating with Gloria Steinem quotes.

Then there’s Carly Rae Jepsen, the teen “Canadian Idol” finalist. Her 2015 album “Emotion”, produced by members of Vampire Weekend and Blood Orange, marked her shift from tween Bieber protégé to pop/indie crossover artist — as did her answers in interviews, where she got honest on issues such as feminism.

The teen idol whose transformation embodies all of this best is Miley Cyrus. She started out as a butter-wouldn’t-melt Disney kids’ star, even wearing a purity ring. Then she undid her image bit by bit with every album, until 2013’s “Bangerz”. At first her feminist credentials and cultural appropriation of hip-hop were mercilessly debated.

But the “Bangerz” tour that followed — a high-art exploration of music placed in the incongruous setting of a tween pop concert — silenced the critics and won her a legion of new appreciators. I remember watching this show, including a 50ft dog shooting lasers from its eyes, and a magic mushroom trip recreated with Jim Henson-style monsters, and wondering whether I was at The O2 or MoMA.

Cyrus then spent the next couple of years supporting homeless youth in Los Angeles through her Happy Hippy Foundation and performing with some heroes of counterculture, including Joan Jett and 1960s protest singer Melanie Safka. Further eschewing the traditional pop artist mould, her most recent project, “Miley Cyrus & Her Dead Petz”, was a collaboration with the Flaming Lips and featured vocals from indie weirdos such as Ariel Pink. Her record label deemed it so uncommercial they allowed her to release it for free online. Cyrus was no longer the woman swinging from a wrecking ball but an important cultural disrupter.

Of course, artists maturing their sound as they get older is nothing new, but the traditional route for a pop star to gain respect from the cool crowd was for them to stop making pop music — that’s been true across the decades, from John Lennon to Charlie from Busted.

Yet none of today’s versions, such as Bieber and Malik, are disavowing their pop roots. Rather, they are becoming standard-bearers for the genre that made them, mixing up elements of R&B, electronic dance music and hip-hop to change the sound of pop altogether and helping to create a genre-less future.

Now, that cycle continues, as the child stars of today follow Cyrus, Malik and Biebs’s model. Take Rowan Blanchard, a 14-year-old Nickelodeon star: her life is not that different to how Cyrus’s was at the same age, except that Blanchard is currently on the cover of style mag “Wonderland”.

Her friend, 17-year-old “Hunger Games” actor Amandla Stenberg, is part of folk duo Honeywater: she’s been an active supporter of the Black Lives Matter campaign and posted a series of videos explaining intersectional feminism. She was on the cover of “Teen Vogue” talking about American race relations with intelligence and subtlety, in a way few adult stars ever have.

Completing this new teen set are Willow Smith and Jaden Smith, the children of Will and Jada, who have both talked about their ambitions to deconstruct gender and R&B. Willow’s self-released, self-produced album “Ardipithecus” last December was a stroll through various disconnected genres that underlines just how unpredictable pop music has become.

That’s the most exciting thing about the new teen stars: they’ve hurled the starting point for the next generation wildly leftfield. What happens now? The next big teen pop album could be produced by Oneohtrix Point Never. Grown adults could be pestering the DJ to play “that massive new Halsey tune”. Sophia Grace in concert might become the hottest ticket since Radiohead at the Roundhouse. The field of pop is wide open and everyone is game.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd