New Delhi: “Delhi has witnessed seven capitals in as many centuries. Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan established his capital in Delhi in 1639 and named it Shahjahanabad. The magnificence of the Mughal era could not be wiped out from the minds of its denizens even when the British took over the city of Delhi in 1857,” writes Sumanta K Bhomick in Princely Palaces in New Delhi (Niyogi Books), a book that gives an elaborate account of the making of the various palaces of early 20th century Delhi.

Shortly after ensconcing itself, British authorities realised the worth of holding ‘Imperial’ Durbars where the loyal subjects would pay obeisance to the Crown.

As the layout for the new Capital was being worked out, several maharajas expressed the desire to build palaces in Delhi.

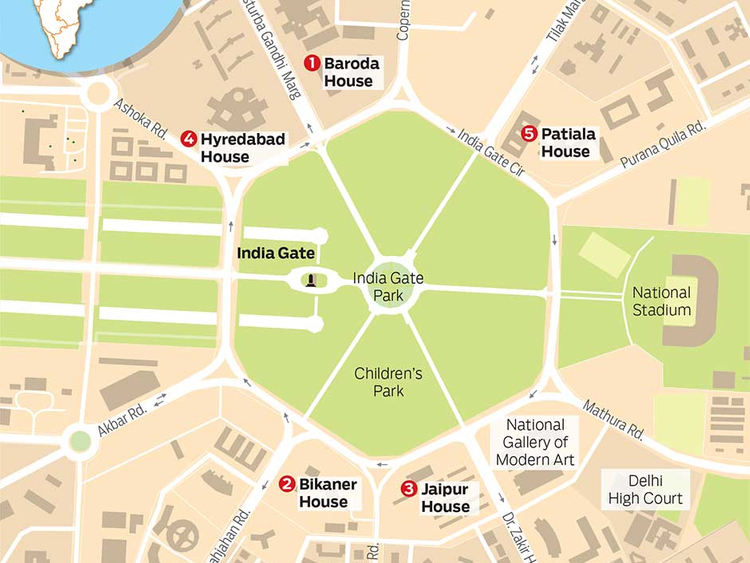

The Viceroy was only too willing and in 1911, the princely states of India were allotted land to build their palaces — largely in Princes’ Park, the area around War memorial India Gate.

Of maharajas and the British Raj, Bhowmick tells several stories - the very first time after four years of extensive research.

Like thousands of people Bhowmick (while working in the Parliament House) passed by the sprawling edifices that were named after the erstwhile princely states. But he did more than just glance at the buildings.

He visited the country’s various historical archives and met some erstwhile royals to gather interesting details of the palaces that have over the years been converted into art centres and government offices, even though their architecture remains the same.

Providing a first hand account of the elite’s social life of the times, he describes how the maharajas would come to New Delhi every year in February for the meeting of the Chambers of Princes, they would arrive in fancy cars with pomp and show, which often led to traffic chaos, how they later built their palaces in the Capital and threw lavish parties in which the crème de la crème sported their finest jewels and foreign-tailored suits.

Taking us on a virtual historic tour, the author narrates the stories behind the royal abodes. For instance: Everyone in the British establishment saw the Maharaja of Bikaner Ganga Singh, with appreciation.

He was regularly invited to luncheons and dinners by the British elites, including Viceroy Lord Irwin and Commander–in-Chief Field Marshal Sir William Birdwood. A war veteran, the maharaja was greatly regarded by the British and other princes for his bravery and uprightness. So, while all other princely palaces in Delhi were requisitioned for war purposes during World War II, the maharaja’s palace was purposely left out.

Another journey takes us to the Nizam of Hyderabad Mir Qamaruddin, who was a combination of power, strength, riches and odd habits. He would dress in wrinkled clothes, wore the same cap for years and would never bathe for days together. Hailed as the richest man in the world by Time magazine, his assets were roughly estimated at about 500 million dollars in gold and another 2,000 million dollars in property and jewels. He had a fleet of 60 enviable cars fitted with gold accessories, but preferred not to drive them for fear of fuel cost. Though a committed miser, he was a generous donor for the right causes.

The coffee table book, filled with old photographs, letters and maps, focuses on the seven main palaces (known as ‘house’) of the states and touches on the others scattered around the city.

BARODA HOUSE

(Present occupant - Northern Railways Headquarters)

Sir Edwin Lutyen conceptualized it on a train journey. While the steam engine trundled on its long way, the architect tried his best to draw a diagram of the proposed Baroda Palace at Delhi. A simpler building, it was constructed in bungalow style that suited the Western tastes and preference for oriental opulence of Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III. The palace exuded an atmosphere of British affluence: its furnishings were Anglo-Saxon and plumbing American. The cook and bandmaster were French, the stable master Irish and the valet and maids English. While the table linen was woven to order in Belfast, the dinner service was fashioned in Bond Street. The maharaja hired Britons to run his army and police force, his hospitals and colleges.

Lutyens was assisted by one of the major contractors of Delhi, Sobha Singh, for the construction of Baroda House. Having started in 1921, its construction took over 15 years. A Victorian look was imparted to the entire façade by adding innumerable arches to the verandah, which gently melted into the roof and was supported by smooth, rounded, elegant pillars. Each room has a fireplace of brick and mortar, lined up with marble that reminds us of the remnants of the British Raj. Sadly, the fireplaces are now being used for keeping files.

BIKANER HOUSE

(Present occupant – Rajasthan state government offices)

The land was duly inspected by Maharaja Ganga Singh during the Conference of Princes in Delhi and Seth Lachman Das, who had already completed the Parliament House building, won the contract for building Bikaner House by quoting the lowest tender. An agreement was signed between the government of Bikaner and the contractor for the construction of the palace, along with staff quarters, outhouses, compound wall and pathways. The maharajah had an elaborate list of requirements, which he forwarded to the architect for strict adherence. The architectural style of the palace did not reflect the aspects of Rajput tradition, but the rooms had been designed to conform to the strict segregation of public, private and women’s wings.

The general design and the façade were greatly western. The maharaja knew it well that the palace would be chiefly used for short stays in Delhi and for entertaining his British guests and fellow princes, the latter group also being imbued with western cultural traditions. Whenever invited for dinner, the viceroy and other dignitaries would arrive at the main porch and head straight to the dining hall after crossing the drawing room. The total expenditure incurred for the construction, including land price, architects fee, electrical and sanitary fittings, furniture, air-conditioners and gardens was estimated to be Rs.12,39,202.

JAIPUR HOUSE

(Present occupant – National Gallery of Modern Art)

Larger than those of other palaces, the saucer-shaped dome of Jaipur House is visible from a distance. The circular drum, on which the dome sits prominently, is decorated with Mughal patterns and plain red bands. No special demand was made regarding the architecture, yet chhatris and other decorative elements on the roof and jharokhas had been incorporated to highlight the age-old Rajput style designs. The lobby and the lounge have witnessed many social functions in the past. The front gate pillars of Jaipur House bore the carved marble replica of the Ashokan capital long before it was adopted as the national symbol in 1950.

The maharaja invited Sir Edwin Lutyen’s son Robert Lutyens, a famous interior designer in London, for decking up the Jaipur House. The palace became famous for holding gatherings in the 1940s and 1950s. Nowhere in Princes’ Park would one find any princely palace like Jaipur House that boasts of works of art by renowned artists and sculptors that are showcased in the open. It also preserves the works of modern painters and sculptors in its appreciable surroundings and has become synonymous with Indian modern art; more so as elaborate exhibitions and installations attract the art lovers and children to its majestic halls.

HYDERABAD HOUSE

(Present occupant – Prime minister’s guesthouse for foreign dignitaries)

Once belonging to Mir Qamaruddin, the first Nizam of Hyderabad, who was hailed as the richest man in the world, the Hyderabad House is one of the earliest constructed palaces that still retain the old-world charm. Though he led a spartan lifestyle in Hyderabad, the Nizam took the initiative to decorate his palace in Delhi with exquisite furniture made of rosewood and walnut. His visits to Delhi presented a great occasion for celebration and he hogged the limelight whenever he went to meet the Viceroy or the times when the princes’ paid return visits. The palace gate was manned by guards in blue tunics touched with gold and in headdresses boldly marked with yellow ocher of Hyderabad.

Out of a total of 38 rooms in the palace, 12 rooms and banquet halls are presently used by the ministry of external affairs as venue for the prime minister to hold receptions for the visiting foreign dignitaries. A 100-foot-long wall-to-wall hand-woven Persian carpet, seven original chandeliers with crystals, original clock and barometer still adorn the banquet hall. At least 60 people can have their meals together seated at the 77-foot-long dining table covered with a single 30-metre-long table cover. It takes 10 people and a crane to carry the carpet to the ground floor to be washed once a year.

PATIALA HOUSE

(Present occupant – Patiala House Courts)

Although the boundary wall of Patiala House was built in 1933, the construction of the building began in 1938 by Maharaja of Patiala Yadavindra Singh, son of Maharaja Bhupinder Singh. The palace is remarkable for its conglomeration of chhatris, a long, continuous chhajja and protruding balconies, but bereft of the dome that dominated all other palaces. It was temporarily placed in a state of emergency at the disposal of the government, free of rent, at the beginning of the Second World War in 1939. During the period, the maharaja was allowed just a corner under the staircase on the ground floor and the entire first floor for his residence, leaving the rest of the building for War Office use.

Again, after Independence, New Delhi faced a great crisis of accommodation and many people took shelter in Patiala House. The maharaja had reserved for himself only the first floor, but was hard pressed by the government to part with more. He wrote letters to the Government of India expressing his inability to allow usage of more space, but later agreed to the proposal. The royal family vacated the palace by 1963 and Delhi High Court temporarily occupied it. In 1978, the district courts were shifted to Patiala House and the building is now home to 32 courts and chambers of the lawyers.

TRAVANCORE HOUSE

(Present occupant – Kerala state government offices)

It was built by Maharaja Sree Padmanabhadasa Sree Chithira Tirumal at a total cost of Rs.400,000. The main gate of the palace still bears the royal crest of two elephants and a conch right on the top, as they were placed hundred years ago. Wealth and fame had never guided the daily lives of the Travancore royal family. They exuded simplicity in their demeanour, both public and private. Everything in this royal house was done in a subdued manner. The bedrooms in this palace were done artistically in different shades and were referred to as – Grey room, Yellow room, Red room and Buff room.

Many guests including the Raja of Cochin and the Nawab of Bhopal used to occupy Travancore House during their visits to New Delhi, as they did not have their own palaces in the Capital. Unlike the princes and chiefs of other princely states, who congregated at Delhi on every occasion, the maharaja of Travancore was far removed from the social revelry. He ate only vegetarian food cooked in the palace kitchen in an orthodox style - sitting on the floor, which was not considered a deserving practice in the glitzy cocktail parties thrown by the princes in Delhi. In 1938, Travancore royals stopped being a part of the regular celebratory processions.

DARBHANGA HOUSE

(Present occupant – Government of India offices)

Maharaja Kameshwar Singh built the beautiful white double-storey building, in 1928. It was known to be the favourite destination for the social elite in pre-Independence Delhi. Proving to be the confluence of the best of the East and the West, it embraced the finest etiquette and traditions of India and Britain and had the most lavish spreads of food and drinks from both the worlds. The last in the line of Darbhanga zamindars, Singh was educated in the Western system and was a perfect mix of traditional and western values. He was the youngest delegate to the Round Table Conference held in 1931 in London.

The maharaja would grant audience to his guests from the palace’s hall, which led from the portico of the main building. He was very attentive to the minute details of the interiors. He was served tea on an entirely moulded glass table that was talked about even among members of royal families. He also owned a tea table topped with a huge, single jade stone. The maharaja’s association with the leading businessmen, politicians, bureaucrats and royal families brought him to the centre stage of a throbbing social life in the Capital and the lavish parties at Darbhanga House attracted a bevy of handsome, beautiful and powerful people.