San Francisco: Maura Sparks is sitting on stage with a small, blue cartoon robot on her lap. This is the first prototype of Smarty, she explains, a voice-controlled digital assistant Sparks hopes to attract funding for and launch in late 2017. New gadgets are launched every day in San Francisco, but this personal assistant has a twist: it is the first intended purely for children.

“The best way to describe it is Amazon Echo for kids,” explains Sparks, the co-founder of Siliconic Home. Addressing the audience at a recent conference in San Francisco on digital technology for children, she said Smarty is designed for kids aged between five and 12.

It will answer their questions, remind them when homework assignments are due, wake them in the morning, control their bedroom lighting, and stream music and audio books. Parents can monitor the child’s activity through a web-accessible dashboard.

“It is something a child can use from the moment they wake up to the moment they go to bed,” Sparks says.

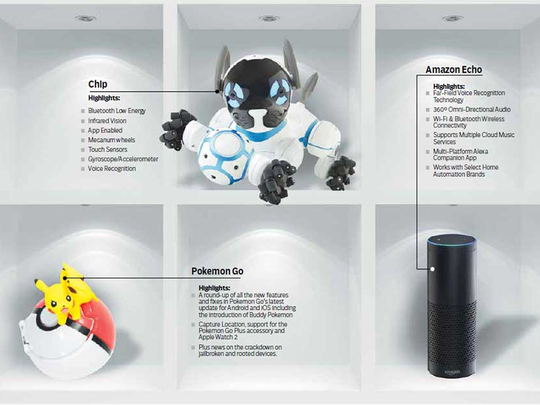

Annual smart-toy sales worldwide are expected to grow from about $2.8 billion (Dh9.2 billion) in 2015 to $11.3 billion by 2020, according to UK-based analyst firms Juniper Research. Digital toys and internet-connected devices for children, such as Smarty, are a rapidly growing part of that, along with intelligent building blocks, smart racing cars and drones, robots that teach kids how to code, and even a smart rubber duck aimed at the very young. There is now a $200 trainable robot dog called Chip on the market, a $200 SuperSuit for laser tag that will begin seeking crowdfunding later this month, and ROXs, a $129 system to entice kids to run around the back garden that will launch soon.

“The industry is getting away from just the screen,” says Tonda Bunge Sellers, who organises the Digital Kids event. “The app is going to the background and the toy is where you interact.”

Swapping screens for toys

Smart toys are gaining in popularity, partly because of a concern about kids spending too much time looking at screens, she says.

“The physical is making it make more sense to the parent,” Bunge Sellers says.

“Last year the connected toy was an outlier, this year it is a trend, and by next year synching your phone or tablet to a toy will be as common as putting double A batteries in,” says Warren Buckleitner, editor of the Children’s Technology Review website. He welcomes the crossover between toys and screens, saying that when the technology becomes less visible, play comes to the fore.

“We can begin talking about the quality of play and child development and not just whether screens are good or bad,” he says.

But while physical toys certainly have appeal, swapping screens for connected toys doesn’t necessarily mean better experiences for children. Stuart Brown, an expert on play and founder of the not-for-profit National Institute for Play based in Carmel Valley, California, says that kids need real, authentic play — activity done for no purpose other than its own sake and where the outcome is secondary to the experience.

Pure play with a side effect of learning is key to creating balanced people in life, he argues. And authentic play experiences with technology are possible if the technology is designed properly, he says.

Mark Schlichting is a children’s design specialist, CEO of NoodleWorks Interactive and author of the forthcoming book Understanding Kids, Play and Interactive Design: How to Create Games Children Love.

The hit screen-based games Minecraft and Pokemon Go show that technology can enable pure play, he argues, engaging kids using classic, hard-wired ‘play patterns’.

Minecraft appeals to the builder-creator instinct, while Pokemon Go appeals to children’s collector spirit — and both involve social play.

Criticism

These play patterns help to keep children engaged beyond the initial novelty of a device or game. But Schlichting warns that most connected toys aren’t there yet, and that “we are only at the beginning” of designing them for authentic play.

Schlichting reminds parents of the importance of choosing age-appropriate toys that match the age and stage of children (too hard is frustrating, too easy is boring) and put them in control; he says young minds open up when empowered. Kids want to know what it is, what it can do and what they can do with it, he says, and also like surprises and unexpected connections.

Others worry that some digital worlds are too controlling and don’t encourage a child to use his imagination — one of the criticisms levelled at the Mattel conversant connected doll, Hello Barbie, released last year.

“I find some connected toys very upsetting,” says Dorothy Singer, a Yale University psychologist who studies imaginative play. She explains how if a child is given a stuffed animal he or she can use their imagination to talk to it, give it a name and use a voice for it. If the toy already comes with a voice and personality there is less room for a child to be creative and make up the story themselves.

“It takes away the child’s contribution,” Singer says.

Both Schlichting and Brown would like to see parents less concentrated on making their kids digital diets too full of overtly educational content.

“For children play is serious learning; it is the real work of childhood,” says Schlichting.

Sparks thinks that Smarty can navigate all these challenges, improve kids lives and optimistically predicts she could sell two million units annually in the US at $99 per unit.

Privacy

She is already preparing for concerns about privacy and data usage when Smarty does see the light of day. Most connected toys are able to send the manufacturer data on how kids are using them, but Sparks says the information Smarty gathers will be stored anonymously and never offered to a third party.

The National Institute for Play’s director of development, Kristen Cozad, likes the concept of smart toys. Programmed to provide what is asked of it, “the experiences are driven by the child, not the toy”. But others worry about a machine interposing between parent and child.

“We’ve been worried about parents handing off the iPhone or iPad ... are we going to do the same thing with this?” asks Chip Donohue, director of the Technology in Early Childhood Center at the Erikson Institute in Chicago. Just like adults when Siri first appeared, it won’t be long before kids are trying to trick Smarty, says Schlichting.

In the name of keeping up with kiddie humour, it had better do something impressive when asked to make a fart sound, he says.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd