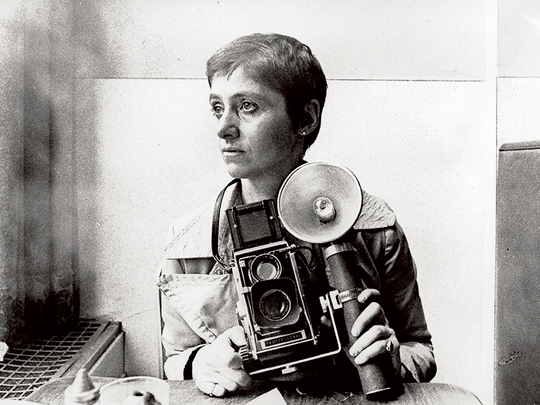

Diane Arbus: Portrait of a Photographer

By Arthur Lubow, Ecco, 752 pages, $35

The poet Paul Valéry wrote that anyone preparing to venture into the interior of the psyche had better go armed. It’s a warning to be heeded by the biographer, especially when his subject is as difficult as the photographer Diane Arbus (1923-71).

Arthur Lubow, a journalist, confronted a figure heaped in myth, an artist-suicide whose work cannot be disentangled from the tragedy of her depression and death. In his 700-page investigation, he laboured in the moonlight penumbra of those other fatal female luminaries: Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton and Francesca Woodman.

Lubow never mentions this “tradition”, but it forms the climate of critical and, above all, popular perception of the work. Likewise the sensational appeal of the subject matter: the sideshow characters, sword swallowers, dwarves, cross-dressers, nudists, giants and — most problematic — people with severe intellectual development disorders. “Freaks” Arbus herself called them, and Lubow frequently repeats the term. The nervous-making frisson these photographs set off when they first began to appear in 1960 can still be felt. Vampire or artist, exploiter or truth teller, genius or purveyor of spectacles that play to the cheap seats: the biographer is forced to take a stand on Arbus, even today.

Lubow went armed. The book is based on substantial interviews with Arbus’s friends, lovers and others, and on documents that hadn’t been available until now. It revisits issues and incidents reported (to much consternation) in Patricia Bosworth’s 1984 biography. It fleshes out — gives truly carnal context to — the biographical timeline published in “Revelations”, the book accompanying the landmark exhibition of Arbus’s work in 2003. That book provided extensive quotations from Arbus’s diaries and letters, as well as a kind of inventory of holy relics, from pages of a high school autobiography to contact sheets to the lugubrious pictures she ripped from tabloids and pinned up next to her bed. It seemed to sanctify her as an artist-saint at the same time that, for all its biographical paraphernalia, it revealed less about the person than met the eye.

But it had one thing Lubow did not: the cooperation of the artist’s estate. None of the more than 150 photographs Lubow mentions are reproduced in the biography. The estate would not grant him permission to use them. This writer — and others — have encountered the same roadblock. The estate’s permission depends on its review of any text to be printed, and it has asked writers to revise offending passages. Since the estate is controlled by Arbus’s two daughters, Doon and Amy, we can imagine that there would be sensitivities about attempts to connect the life with the work and to pry deeply into the life.

Pry he has. Lubow charts every up and down of Arbus’s private and emotional life during what was, after all, a fairly brief creative career, less than 20 years. Symbolically, Lubow begins with the moment Arbus decided to end her successful photographic partnership with her husband, Allan Arbus. She couldn’t take shooting fashion anymore. Then he flashes back and commences the long story of her fraught life. The reader has a right to ask whether, given the length of the book and its comparatively superficial engagement with the many issues raised by Arbus’s life and photographs, so detailed a biography is a big hammer for a small nail. Yet chopped up into 85 short chapters, with breathy titles such as “Freak Show” and “I Think We Should Tell You, We’re Men”, the book reads more like a novel — salacious, mysterious (another favourite word of hers) and harrowing.

In this “novel”, rumours that have circulated for years are confirmed, and the reader is left to draw some disturbing conclusions. According to Lubow, Arbus maintained a sexual relation with her brother, the poet Howard Nemerov, that began in childhood and was renewed, once again, just before her suicide. Her emotional and financial dependence on Allan lasted throughout her life, to the point when he was about to make their decade-long separation final via divorce. And her intense relationship with the artist and art director Marvin Israel was apparently clouded at the end by the possibility that he was sleeping with her older daughter, Doon.

Amplifying the novelistic air of mystery are the last pages of her journal, which were neatly cut out and never found after her death. Lubow locates the source of all this emotional turmoil in the Arbus family romance, a story of American social climbing: her father was a Jewish businessman who ran a successful New York department store. He was reserved and judgmental. Her mother was pretentious, insecure and depressive. Diane — pronounced Dee-AHN, as her mother insisted, to set her daughter apart — was “creative” and misunderstood. Her family seems to have bequeathed the artist an enduring sense of unreality, the deep suspicion that she somehow did not exist.

All this is delivered in a formulaic prose that is generally as compelling as a textbook. This reader longed, on the one hand, for more passion and, on the other, for more depth, a diversion of the narrative headway to explore the philosophical connection between eye and body, between seeing and being. An approach that risked turning off a few readers might have taken us closer to the heart of the photographic paradox that Arbus so intensely lived, a relation with reality of approach and avoidance, inventory and alienation, mediated always by that heavy talisman she wore around her neck.

Instead, Lubow relies on Arbus’s famous formulation that a photograph is “a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know.” She was, as the story goes, in search of secrets. He also presents her work in the familiar terms of “expressive” photography, which projects a personal vision instead of documenting reality. It’s a defensive approach against the charges of voyeurism and exploitation levelled most stridently by Susan Sontag and still echoing. Lubow’s sometimes forced symbolic readings of the photographs seem marshalled primarily to strengthen the defence.

Yet the narrative gives us something more important than anything it lacks: the embodied voice of Arbus herself. Many of her quotations are taken from the texts in “Revelations”. They include letters, writings, even captions she wrote for her magazine assignments. Staged by Lubow, however, they emerge out of her ongoing argument with reality, pursued through sex, photographs and words. Arbus is possibly the closest thing America has to Kafka, a profound ironist who simply did not see the world in conventional terms and was — when you strip away the nice-making, the wheedling for money or support and the expressions of garden-variety depression — incapable of saying anything uncompelling.

She once presented a copy of Kafka’s “In the Penal Colony”, which features a monstrous tattooing torture machine, to the tattooed Jack Dracula, one of her sideshow subjects. Her prose is a strange amalgam of silver-spoon educational advantage (although she never attended college) and a diffident vernacular suspicious of fine language. It is the Kafka of the cage that went seeking a bird, in his tiny parable. The biography lives in Arbus’s gnomic utterances, so disarming to friend and foe alike.

One is worth quoting to stand for many. In a postcard to Marvin Israel she wrote: “We stand on a precipice, then before a chasm, and as we wait it becomes higher, wider, deeper, but I am crazy enough to think it doesn’t matter which way we leap because when we leap we will have learned to fly. Is that blasphemy or faith?”

–New York Times News Service

Lyle Rexer’s next book, “The Critical Eye: Fifteen Pictures to Understand Photography”, will be published in 2017.