It is the stuff of legends and fables. Coveted, dreaded, lusted after, loved and longed for, the Kohinoor diamond has ignited great passion, and left behind a legacy of war, death and destruction.

No less than five different nations lay claim to it. Originating in India, the diamond finally passed into the possession of the British in 1849 and is today housed in the Tower of London, part of the British Crown Jewels. It is the subject of numerous books, and yet another — Kohinoor: The Story of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond by authors William Dalrymple and Anita Anand — has hit the stands.

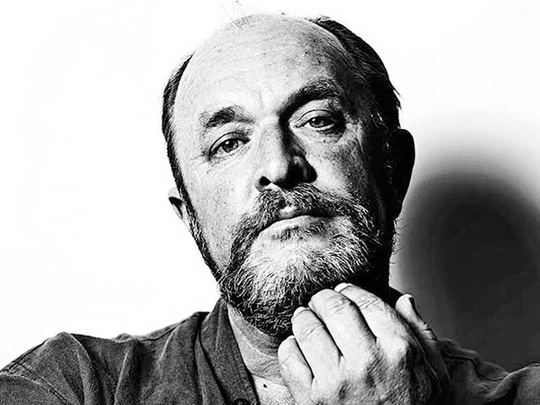

On the sidelines of the 2017 edition of the Tata Steel Kolkata Literary Meet, William Dalrymple spoke about the making of the book and how much of the history associated with the diamond has been nothing but myth.

Excerpts:

Why write about the Kohinoor again?

It was clearly something that contains so much misinformation and clearly ignites so much passion, and so it’s an incredibly important subject. We decided to write it after the ridiculous statement that the Indian Attorney General made last year that [Maharaja] Ranjit Singh had given it to the British freely. It wasn’t Ranjit Singh, and it wasn’t given freely. Ranjit Singh was in fact dead by the time the Kohinoor passed to the British in 1849, as part of the Treaty of Lahore [which marked the end of the second Anglo-Sikh war]. One of the main stipulations of the peace treaty was that the diamond goes to the Queen [of England]. So it wasn’t a gift, and that was what had us persuaded.

What are the myths and what are the facts?

There is elaborate early history given for the Kohinoor in most accounts, all of which is purely fiction. There is no reference to the stone in any certain sense before 1750. So all this stuff — that it was found and discovered in the south, mined by the Kakatiyas, put in the eyes of some idols, taken by the Khiljis, taken by the Lodhis, taken by the Mughals, passed in the turban of [Mughal Emperor] Mohammad Shah Rangila, then the turban swap of Mohammad Shah Rangila with Nader Shah — none of that is at all factual. It’s all myth-making. We know the greatest myth-maker was Earl Theo Metcalfe, a drunken young British magistrate in Delhi.

What were the main sources you used to write the book?

It’s drawn on hundreds of sources — Persian, Afghan, English, records of Duleep Singh’s family. The really exciting [part] was discovering the missing Persian sources, which give 18th century history. The first quote that refers to the Kohinoor is by one of Persian King Nader Shah’s soldiers, Mohammad Marvi, in 1750. It is a very explicit eye witness account — Mohammea Marvi says: “I have seen the Kohinoor. It is attached to the head of the peacock of the Peacock Throne.” That reference is in a Persian chronicle narrating Nader Shah’s invasion of Delhi and the Mughal Empire in 1739.

Discovering the part of the passage which explains how it went to Ahmad Shah Abdali, and then discovering Theo Metcalfe and how the whole myth-making had taken place [was also exciting]. In 1849, the same year that the diamond was passed [over] to the British as part of the Treaty of Lahore, [British Governor General Lord] Dalhousie who signed the treaty asked Theo Metcalfe to find out what he could about the Kohinoor. And by Metcalfe’s own account what he found out was thin on fact. This is more or less the history that is relayed to everyone since that moment. So I think we nailed it. Of course, more stuff may turn up in the future but I think we managed to destroy quite a lot of the myths and build up a whole new factual history with proper sources to them. It’s broken a huge amount of new ground.

What would you say was the most important myth that was busted?

The whole of its legendary early history which gives it a past going back to antiquity and gives it a past right through several dynasties before the Mughals. There is no 100 per cent reliable reference to Kohinoor at any point in time before 1750, by which time it had already left India and was part of Nader Shah’s loot [of Delhi].

We don’t know how it came to the Mughals, we don’t know when it came to the Mughals, we don’t know where it’s from, we don’t know whether it’s mined — we don’t know anything until the 17th century. [Before] the Peacock Throne it seems to have been knocking around for several years, but none of that is known. We proved that its early history was false and established that it was part of the Peacock Throne.

Did your research shine any light on why the Kohinoor is the diamond most spoken about and most written about?

Absolutely. It’s because of the Great Exhibition, which put the Kohinoor on show at London’s Hyde Park in 1851. A third of the population of Britain queued up to see it and it was on the front page of every newspaper. That was the moment when it really went on to become ‘The Diamond’. The Mughals hardly referred to it at all, Nader Shah refers to it glancingly, the Afghan sources refer to it a bit more, and here it becomes the centre of all attraction.

What has been the response to Kohinoor, the book?

Fabulous, it’s doing so amazingly well. Despite the demonetisation and collapse of the book market following it, it’s been fabulous and most of the reviews have been good.

What would it take for the British to return it to India?

I can’t answer on behalf of the British government. I certainly do believe that there should be apologies and education but of course my politics are quite different from that of the current government. I can’t imagine any situation where it would come, which is not to say that it shouldn’t come. At the end, we just give various options... building a museum on the Wagah border where the Pakistanis can see it from one side and the Indians could [see it] from the other. Maybe splitting it up between India, Pakistan, Iran and Afghanistan. There are so many claimants to it. These are all ideas we have mooted but I think realistically it will remain in London.

What is your personal opinion about it?

I’m entirely sympathetic to Indian expectations. It came from India after all but I think it’s important if you are writing a history, everything about this written so far has been polemic without facts. We tried to produce facts without the polemics. So I think it’s important that we close the book establishing the facts and let the reader come to conclusions. If they want to use our facts to prove the case, I would be very pleased.

Since the diamond originated in India by all accounts, and in a part of India that is still within the territory of modern India, does that not give an extra edge to India’s claims to the diamond?

Except for the fact that all over the world there are diamonds which have gone by violence to the victor. The Darya-e-Noor and the great Indian diamond [now known as the Orlov], both of which are larger than the Kohinoor and are in Iran and Russia, originated in India. I think the diamond has produced greed, envy, dissension throughout history and continues to do so.

Who is your favourite character in the book?

Ahmad Shah Abdali because he has this gruesome end with one half of his face eaten up by maggots. Of course, he’s not someone I would want to have dinner with. If I had to choose who to have dinner with, it would probably be Mohammmad Shah Rangila. He clearly was a whole lot of fun: he was a poet, he loved women and was an extremely interesting character.

You have been part of the Indian literary scene for a while now. What do you feel about its growth?

When I first started there was only one publishing house — Penguin India — and it was publishing in small quantities. Now publishing is a major industry here. All major international publishers have divisions. There were no literary festivals when I came here and now there is one every time. There was no nonfiction, no literary nonfiction, being written. It was all novels. Now it is hugely profitable, hugely vibrant, but there isn’t a generation of writers like there was in the 1980s — Amitava Ghosh, Shashi Tharoor, Salman Rushdie — who were a dazzling generation of novelists. Now we have the bookstores, the infrastructure and the sales, but at the moment no major superstars. The major superstars of Indian writing in English are all from outside India [such as] Suketu Mehta and Jhumpa Lahiri.

But these things can change. Ten years ago you had a literary scene in Pakistan — Mohsin Hamid, Daniyal Moinuddin — but now that’s gone completely quiet. So these things come and go. We are not particularly in one of these moments but we have an extremely strong base now to grow out of. And the most important change is now you can support yourself in India as a writer — there are now the economics of it. Earlier it was simply impossible. Vikram Seth was working in the World Bank, someone else was in advertising. You couldn’t imagine making a living out of being a writer but now you can.

Who is your favourite Indian writer?

Very difficult to answer. There are many. Among my generation, probably the greatest writer of nonfiction is Suketu Mehta. Jhumpa is probably the greatest novelist in the diaspora, and probably Arundhati Roy. I have to see if she keeps it up this year.

Are you working on another book right now?

I have a big book coming up on the East Indian Company. Shashi Tharoor, in his book, has drawn a lot from my work. His opening sentence about the loot in India is taken from an article of mine.

Aditi Bhaduri is a freelance journalist based in India.

PULLQUOTE: There is elaborate early history given for the Kohinoor in most accounts, all of which are purely fiction