Dr Christopher de Hamel has achieved an unmatchable feat. His recently released book, “Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts”, places him in the category of the finest writers (with his irresistible wit and enthusiasm) as he takes readers on a journey around 12 of the most precious medieval texts. Spectacularly illustrated, the book includes the world’s greatest collections spanning 1,000 years from the late sixth to the 16th centuries.

Author of numerous books, he challenges in the introduction: “Try to have the ‘Book of Kells’ removed from its glass case in Dublin so that you can turn the pages. It won’t happen. The majority of the greatest medieval manuscripts are now almost never on public exhibition at all, even in darkened display cases, and if they are, you can see only a single opening.”

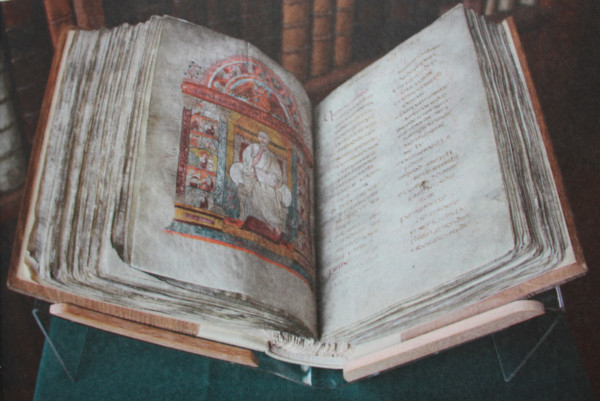

Having chosen a representative range of various medieval books, Chapter One begins with “The Gospels of Saint Augustine” (late sixth century) housed at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. “The Gospels of Saint Augustine is not brought out easily for casual readers. It is immensely fragile and vulnerable and for many people it still has a sacred and spiritual significance.” For the book’s owner, Archbishop Parker, who was appointed Master of Corpus Christi College in 1544, it would have had a primary value in his search for the foundation of Christianity in England in 597.

Considered the earliest surviving book known to have been in medieval England, when it arrived in England, it was probably initially a very practical book, not yet venerable enough to have become a relic, the writer notes.

“Its manuscript is stored in a burglar-alarmed and air-conditioned vault, where it is shelved horizontally in a stout fitted oak box, made in 1993 at the expense of an architect and old member of the college, Roger Mears, whose name is recorded on a leather label.”

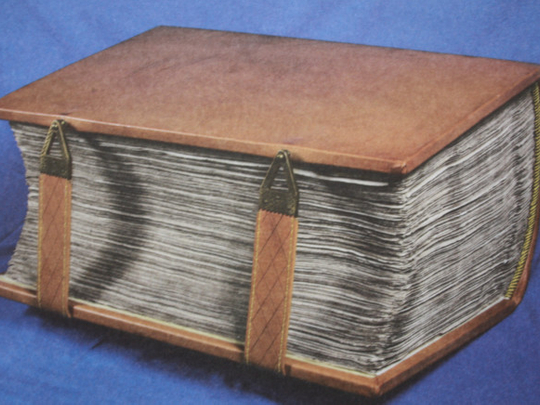

About “The Codex Amiatinus” (circa 700), Florence, Biblioteca Laurenziana, Dr de Hamel writes: “My first inquiry about seeing the book itself was met with refusal, that deep all-encompassing sigh of infinite regret which only the Italians have perfected: it is too fragile to be moved, I was informed, and it is too precious to be handled. In Italy, however, the word ‘no’ is not necessarily a negative. It is merely a preliminary stage of discussion.”

Understandably, the author did find his way, as he provides a very vivid glimpse of the place where he studied the book. “You approach the library through a gateway in the southwest corner of the Piazza di San Lorenzo, the square in front of the unfinished brick façade of the church. There are Italian and European flags over the entrance, and banners for whatever exhibition is currently on view.

“The steps lead up past faded frescoes on to the upper level above the eastern range of the cloister. The first door is the public entrance into the staircase to the library room built by Michelangelo and still with its ranks of sloping book presses. The second door, beside a terracotta pot, takes you into the library office.”

About the more than 2,000-page book, he writes, “It is not so much tall, for many late-medieval choir books are of larger dimensions, but it is almost unimaginably thick. The manuscript is bound in very modern plain tan-coloured calfskin over wood with leather straps dangling from the lower board stitched with yellow thread and fitted with modern brass clasps which reach up to metal pins set in the edge of the upper cover. It looks, frankly, like a huge and expensive Italian leather suitcase.”

The “Book of Kells” (late eighth century), Trinity College, Dublin, has reportedly been stolen twice. It takes its name from the town which once owned it and from which it had been stolen in 1007). It is a manuscript of the four Gospels — Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

Dr de Hamel calls it “the most famous book in the world”. It “risks being mobbed, like a pop star or a head of state. The security arrangements around it are necessarily as complex as presidential protection undertaken by the secret services of a great nation,” he writes.

About “The Morgan Beatus” (mid-10th century), Morgan Library and Museum, New York, he writes: “The standard rules sent out several days in advance to people who apply to use manuscripts ... include an instruction which I have not encountered elsewhere: ‘Please refrain from wearing coloured fingernail polish, since it might leave marks on the rare material that you are handling.’

“It is an intriguing if unusual rule. Frivolous glitter and cultural consciousness go hand-in-hand in the wonderful modern Babylon, which is New York. I had written to the Library for permission to see their 10th-century illustrated manuscript about the end of the world foretold in the Apocalypse. Morgan [M 644, as it is] is famous for its large and graphic scenes of tumult and ruin, and the expected judgment and destruction of civilisation. As I walked up Madison Avenue, amid that relentless noise of the city, the fury of yellow taxis and howls of police cars, the clangour of construction, the bursts of satanic steam from underground heating vents, and all the strident frenzy of commerce, I could call to mind so many apocalyptic disaster movies set among these soaring towers. It all seems imaginable here.”

In the chapter on the “Copenhagen Psalter” (third quarter of the 12th century) Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen, he writes: “If manuscripts were accompanied by music, the ‘Copenhagen Psalter’ would have trumpets and a church organ. Every page of the manuscript shimmers with burnished gold and splendid ornament. The script is calligraphically magnificent. The volume opens the 12 pages of an exquisite calendar of saints’ days written in multiple colours, and then, before the start of the first psalm, there is a sequence of 16 full-page pictures, which are truly breathtaking and are the glory of this manuscript.

“The calendar reveals an unmistakable flavour of its English ancestry. It is written in black ink, but significant feasts are singled out gaily in red, blue or green. Although not illustrated, it is certainly festive in every sense.”

The original 13th century manuscript of the “Carmina Burana”, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, “was discovered uncatalogued among the books in the library there after the suppression of the monastery in 1803 during the Napoleonic reforms. It contains about 350 poems and songs, many of them unique, of which only about 20 pieces or extracts were eventually set to modern music by Orif. Most are in Latin, but the volume has scraps in various European languages and important pieces in Middle High German, which are among the oldest surviving vernacular songs. The manuscript of ‘Carmina Burana’ is by far the finest and most extensive surviving anthology of medieval lyrical verse and song, and it is one of the national treasures of Germany.”

Dr de Hamel is associated with Corpus Christi College and is Fellow Librarian of the Parker Library, one of the most important small collections of early manuscripts in Britain. He has doctorates from Oxford and Cambridge and honorary doctorates from St John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota, and Otago University, New Zealand. He is a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and a member of the Comite International de Paleographie. He spoke to Weekend Review about “Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts”. Excerpts:

“Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts” has been described as “the best chance to see the world’s most beautiful manuscripts”.

One of the difficulties in seeing the greatest illuminated manuscripts in the world is that the originals are exceedingly valuable, fragile and vulnerable, and it is not easy to get to handle them. Libraries and museums are obliged to be very selective in allowing access. Most people know them only through reproductions or facsimiles. At best, manuscripts are exhibited in glass cases, where only two pages can be seen at once. The idea of this book is to describe, as vividly as possible, what it is actually like to hold a precious manuscript in your hands and to turn its pages, and to experience first-hand some of the most beautiful and important books in the world.

What was the thought behind this unique book?

The idea is to take the readers behind library doors that are not easily accessible to many. Many of the world’s great works of art, including the Sistine Chapel and the Taj Mahal, are generally accessible to anyone with the money or leisure to visit them; but illuminated manuscripts are different. They are not easy to see, unless you are a professional with specialist permission. This book describes what it is actually to do so, and how different the many libraries are.

So, you can safely claim to have catalogued more medieval manuscripts than anyone alive, and probably more than anyone has ever done?

I used to work for Sotheby’s, the auction house, cataloguing manuscripts for sale. We would be seeing many hundreds of unknown manuscripts a year. I suppose it probably is true that — because of that job (full-time or part-time for 40 years), I was able to see tens of thousands of illuminated manuscripts. I am now responsible for an important library of medieval manuscripts at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.

Probably the most famous manuscript, which came through my hands at Sotheby’s, was the 12th-century “Gospel Book of Henry the Lion”, which was sold in 1983 for £8,140,000 — then about three times more than any Old Master painting. But there have been others, including the then-unknown “Spinola Book of Hours”, which is the subject of Chapter 12 in my book. It was found by me in Munich in 1975 and sold in 1976.

Do you have any secret method with which you pursue discovering these remarkable manuscripts?

Absolutely not. “Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts” mentions how discoveries are made. As one turns the pages of a medieval manuscript and looks at it carefully, one will start to notice things, which no one has seen before — marks of how the book was made, how it has been altered, who have owned it and so on. It is really a matter of looking, really looking. It is very exciting, and anyone can do it, if they have access to an original manuscript.

What languages were the 12 works (included in the book) originally written in and on what?

Most European medieval manuscripts are written in Latin, which was the most universal language of literacy. One of the 12 books described here is in Middle English (Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales”); one includes some texts in German (the “Carmina Burana”) and another has some prayers in French. All the manuscripts described are written on parchment and decorated or illuminated with colours and often with gold.

How many years of perseverance resulted in this collection?

The book took me about three years to write, from start to finish, but it draws on a lifetime of seeing and thinking about manuscripts. I saw my first medieval manuscript in 1963. Since 1972, I have worked full-time on manuscripts, and described many of those experiences in the book.

Were there any manuscripts that you wished to include in the book, but could not pursue due to certain reasons?

I love all manuscripts. I don’t mind whether they are beautiful and famous or scruffy and cheap. Each one has its story to tell, and its place in history — just as every individual does and not only celebrities. No one really knows how many western medieval manuscripts still exist throughout the world. They could probably be several millions. I could have included any of them profitably. The selection chosen was almost random, but it was intended to give as wide a range as possible of texts, dates and places where the books now survive. There are manuscripts described here in Cambridge, Florence, Dublin, Leiden, New York, Copenhagen, Munich, Paris, Aberystwyth, St Petersburg and Los Angeles; but we could have had London, the Vatican, Vienna, The Hague, Berlin, Venice, Jerusalem, Cape Town, Edinburgh, Brussels, Chicago and many others.

What are the kinds of topics that you would encourage medieval scholars to explore?

Students, or anyone, looking at any medieval manuscript, can explore many questions. For instance, where was a manuscript made? When? How? By whom? Why? What was it copied from? Who paid for it? What did it cost? Where did the materials come from? How many people were involved? Who were the artists? What mistakes occur in it and what innovations? How was it read? Who could read it? Where has it been? How can we tell? Who has owned it since? When was it bound? Why was it kept? Was it sold, looted, borrowed? What did it sell for? How did it reach the collection where it is now?

It may be a fabulous and famous volume; but it may also be an inexpensive medieval manuscript you own yourself, for, despite the glamour of the manuscripts described in my book, original examples still come to the market and can still be acquired by almost anyone. I welcome everyone to the joy and fascination of examining medieval manuscripts.

Nilima Pathak is a journalist based in New Delhi.