By Celeste Ng, Random House, 338 pages, $27

Readers of Celeste Ng’s second novel, Little Fires Everywhere, will recognise a few elements from her acclaimed debut, Everything I Never Told You. There are the simmering racial tensions and incendiary family dynamics beneath the surface of a quiet Ohio town. There are the appeal and impossibility of assimilation, the all-consuming force of motherhood and the secret lives of teenagers and their parents, each unknowable to the other.

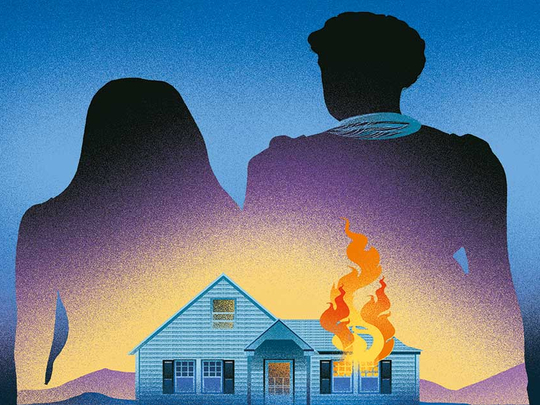

And there’s a familiar frame, too: At each novel’s opening, we know at least part of the tragedy that will befall the characters — the mystery lies in figuring out how they got there. In Little Fires Everywhere, we begin not with a death but a house fire, and new questions: Who set it, and why?

The house belongs to Elena and Bill Richardson, a wealthy white couple who epitomise success in picture-perfect, late-1990s Shaker Heights, and their four teenage children, including girl-next-door Lexie and the troubled prankster Izzy, who is suspected of arson. “The firemen said there were little fires everywhere,” Lexie says. “Multiple points of origin. Possible use of accelerant. Not an accident.” But Izzy isn’t the only one who seems to have fled the scene. Mia Warren and her 15-year-old daughter, Pearl, have also disappeared, vacating the small house they rented from the Richardsons. And so Ng again returns to the past for answers.

It’s Mia and Pearl’s arrival in town 11 months earlier that ignites the story. Mia is an alluring Hester Prynne, a misfit nomad whose scarlet A might stand for Artist. She and Pearl have travelled the country in their VW Rabbit with little more than Mia’s camera, living in dozens of towns before settling in Shaker Heights, where Mia promises her daughter they will stay. Pearl, longing to belong, quickly becomes a fixture in the Richardsons’ home, entangling her mother along with her.

Witnessing these two families as they commingle and clash is an utterly engrossing, often heartbreaking, deeply empathetic experience, not unlike watching a neighbour’s house burn. And the spectacle doesn’t stop with the Richardsons and Warrens. Ng also introduces a custody battle that becomes the centre of the town’s attention — a 1-year-old girl who is wanted by both her Chinese immigrant mother and the white couple who has raised the baby.

It’s this vast and complex network of moral affiliations — and the nuanced omniscient voice that Ng employs to navigate it — that make this novel even more ambitious and accomplished than her debut. If occasionally the story strains beneath this undertaking — if we hear the squeaky creak of a plot twist or if a character is too conveniently introduced — we hardly mind, for our trusty narrator is as powerful and persuasive and delightfully clever as the narrator in a Victorian novel. As soon as we meet our matriarch — “Mrs Richardson stood on the tree lawn, clutching the neck of her pale blue robe closed” — we have the sneaky sense that our well-mannered narrator is speaking from both within and above the order-obsessed neighbourhood.

But as Mrs Richardson — rarely “Elena” — struggles to keep her household in order, the narrator begins to shapeshift, surprising us with the expansion of her powers. Ng doesn’t miss an opportunity to linger over a minor character, even those we meet for only a moment (the neighbour, the doorman, the bailiff) whose voices might otherwise be rendered in parentheses. At the same time, she offers a nuanced and sympathetic portrait of those terrified of losing power. It is a thrillingly democratic use of omniscience, and, for a novel about class, race, family and the dangers of the status quo, brilliantly apt.

Mrs Richardson’s vision of a suburban utopia might strike some as a quaint fantasy, but this is the 1990s, after all. Post-9/11, post-Obama, in the age of Trump and Black Lives Matter, we may know better, but Ng reminds us that 20 years ago, in the age of AltaVista, pagers and Sir Mix-a-Lot, some who voted for another Clinton claimed to have within their sight a post-racial America. “I mean, we’re lucky,” says the blond Lexie, whose boyfriend is black. “No one sees race here.”

The magic of this novel lies in its power to implicate all of its characters — and likely many of its readers — in that innocent delusion. Who set the little fires everywhere? We keep reading to find out, even as we suspect that it could be us with ash on our hands.

–New York Times News Service

Eleanor Henderson is the author of the novels Ten Thousand Saints and The Twelve-Mile Straight, which has just been published.