On a bitterly cold December morning in 2009 at the Xishan Detention Centre in Urumqi, western China, 53-year-old Akmal Shaikh was woken up by a team of guards from the high-security prison. After a quick shower and a breakfast of porridge, Shaikh was escorted out to meet a prosecutor, who read out to him a notification in Chinese — he didn't understand a word of it. Afterwards, he was led to a mobile van, placed on a horizontal gurney and strapped up. Then it all happened rather swiftly — a lethal combination of sodium thiopental, pancuronium bromide and potassium chloride injected into his veins took only about a minute to still his heart.

The execution of Shaikh is only one among the estimated 1,700 to 10,000 death sentences carried out in China every year, though there are no official figures. However, it created international headlines and kicked up a major diplomatic spat. Shaikh, a Pakistan-born British businessman from north London, was arrested and jailed in Urumqi after he was caught at the local airport in September 2007 carrying 4 kilograms of heroin in his suitcase. He had travelled from Poland to China, and officials alleged he had brought the drugs from Kyrgyzstan via Tajikistan. His family and non-government organisations fighting the death penalty argued that Shaikh suffered from mental illness and bipolar disorder, which was exploited by drug cartels, who tricked him into transporting heroin in return for a music recording contract. Shaikh himself, however, denied in court that he suffered from any mental illness. Sometime in 2008, China's supreme court upheld the death penalty handed down to Shaikh by lower courts in Urumqi.

When British prime minister Gordon Brown said he was "appalled" at the execution and Foreign Office minister Ivan Lewis said it was "entirely unacceptable" that Shaikh's mental health was not assessed before he was put to death, the Chinese government and public bristled at the "foreign interference", citing "the bitter memory" of China under foreign imperialism harking back to nearly two centuries.

To thousands of Chinese people, it was a reminder of the Opium Wars of the 19th century between the Qing empire and the British and the French, when, as one Chinese commentator put it, "the confiscation of opium and punishment of British drug dealers led to the first war of China in the century, through which the British forced open the gate of China by opium and cannons". China lost the wars and suffered from its "century of humiliation". One internet user from Guangxi summed up the sentiment for many Chinese in his online comments: "History will remember this date for ever. It's a day that Chinese people held their heads up and it's a day to comfort national heroes … who fought against opium smoking."

Whether Chinese history immortalises Shaikh's execution or not, the 170 years since the first cannon was fired in Canton — triggering the beginning of the First Opium War in 1840 — have been an uncomfortable legacy for both Britain and China and find strong resonance in global geopolitics today, says historian Julia Lovell, an award-winning translator and a lecturer on Modern Chinese History and Literature at the University of London, whose book The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams and the Making of China was published last month.

"The story of Britain's drug-dealings in Asia and of the wars it fought for opium is one of striking opportunism and hypocrisy, as politicians, traders and soldiers concealed their fight to protect an illegal narcotics trade beneath the flags of civilisation and progress," Lovell says in an interview with Weekend Review. "I wouldn't argue that there are any direct analogues in the world today. But countries such as Britain and the United States are still choosing to fight wars in the world for reasons that are not clear. While there was a clear moral impetus to Britain's recent intervention in Libya, several commentators have speculated that the decision was driven by economic imperatives."

Rarely mentioned in Chinese history prior to the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989, and glorified as a lesson on national humiliation thereafter, the Opium Wars (1839-1842 and 1856-1860) occupy a powerful position in Chinese discourse.

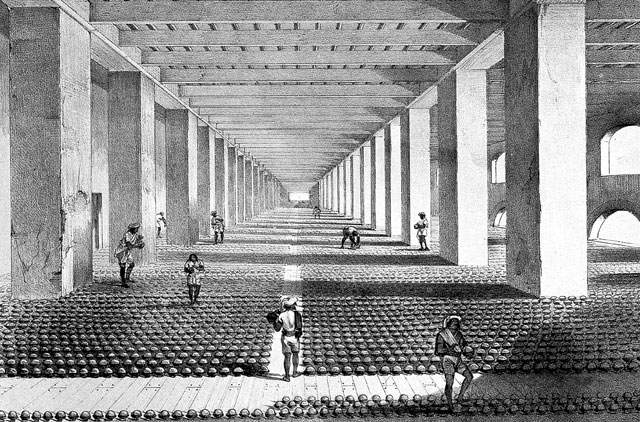

It all started with the British discovering an ingenious trading system to reduce the empire's mounting trade deficit after the conquest of India in the 18th century. By 1790, the deficit had risen to £28 million and swelled much beyond it by 1820, when the British trading community and the government found the perfect solution for the situation: Indian opium. Taking advantage of Chinese fondness for the Indian variety, British merchants bribed Chinese officials to allow entry of chests of opium shipped from British-ruled India, though such imports had long been banned by imperial decree in China. Between 1800 and 1818, the average annual traffic of opium to China was 4,000 chests (with each chest containing about 64 kilograms of opium); by 1831, the number of chests touched 20,000; and by 1840, when the British East India Company had lost its monopoly on the trade and the market was full of private merchants, the sales touched nearly 40,000.

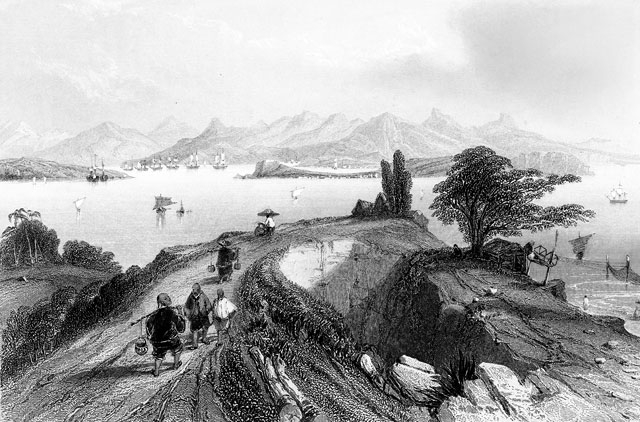

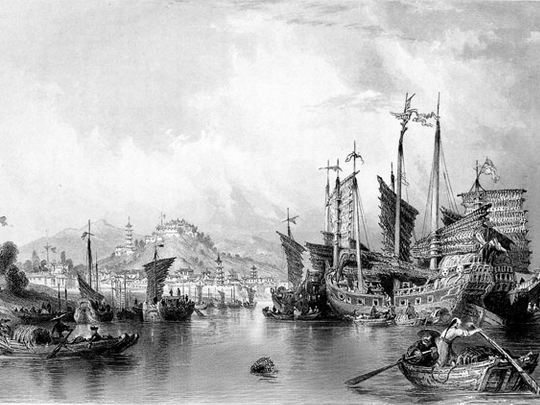

An attempt by the Chinese authorities to control the trade at the port of Canton by destroying large consignments of opium and publicly executing drug merchants resulted in a massive British army from India invading China, running through Canton and seizing the tax barges on the Yangtze. The blow proved disastrous. The Treaty of Nanjing signed in 1842 forced China to pay an indemnity to Britain and open four ports to it, and give up Hong Kong to the Queen. The Second Opium War (1856-1860), led by an Anglo-French coalition, ended in further ignominy for the Chinese: Beijing's famed Old Summer Palace was gutted as a reprisal for the torture of a British mediation team; the treaties signed to conclude the war forced China to open full-scale trading relations with the West, legalise opium trade throughout the country, cede Kowloon and pay a total indemnity of 5 million ounces of silver to the British and the French.

While the wars themselves have been traditionally glossed over as the beginning of a long and sinister plot of foreign aggression (by China) or as enforcing the progress of a moribund empire on the path of modernity (by Britain), Lovell's interpretation of them is far more disturbing for both sides. "This war has long been seen as a collision of clear-cut civilisations — between expansionist, free-trade Britain and xenophobic, isolationist China," she says. "Many still assume that China, since time immemorial, has been an essentially coherent place whose people have always identified with a single, central set of political and cultural ideas. As the country embarked upon its first war with Britain, it was nothing of the sort. It was a fractious, failing empire, scattered with discontent and chancers ready to sell their services to the highest bidder, regardless of his or her ethnicity."

That saga of sheer opportunism raises several uncomfortable questions. For a post-Tiananmen China embarking on a path of reform, aspiring to be a global superpower and aiming to recapture its pre-1890 glory as the world's largest economy by 2015, the Opium Wars have been a critical point of reference in Sino-Western relations. "In Chinese politics, [the Opium Wars] stand for the beginning of a long-term Western plot to harm China. If the West criticises China, the Chinese government can press what you might call the Opium War button: It reminds the Chinese people that the West has always been full of schemes [such as the Opium War] and therefore not to be trusted," Lovell says.

Indeed, China has pressed that button several times — including at least twice in the same year that Shaikh was executed. The first was the Chinese premier Wen Jiabao failing to attend negotiations at the Copenhagen Climate Change Summit, with the West subsequently blaming China for the breakdown of the summit; and the second was the 11-year jail sentence handed to dissident writer Liu Xiaobo, who went on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature the next year.

In a seminal essay published in the Chinese Journal of International Politics that reviews China's position in international society over the past couple of centuries, Barry Buzan,

a professor of International Relations at the London School of Economics, argues that "the rhetorics of ‘harmonious society' and ‘harmonious world' do not remove the worries of outsiders about what a risen China would be like and how it would behave. The choices China makes between the regional and global levels of international society will profoundly shape both the path that peaceful rise takes and the probabilities of its success or failure."

Lovell is even more circumspect of the narrative of Chinese superpower. "Beneath the headlines about China's rise, it's important to remember that the country is a high-wire act: There are probably as many reasons for this complex, diverse country to fall apart as there are for it to hold together. Its government is very concerned about political and social instability; consequently, we're seeing unfold right now one of the most unblinking crackdowns on dissent since the death of Mao," she says.

The crackdown comes hardly as a surprise in a nation where the 150th anniversary of the First Opium War in 1990 was marked as an occasion to "remember our history of humiliation and build a beautiful future", according to a state-sponsored documentary, and where the execution of Shaikh was compared to the "burning of opium stocks in Humen in 1840 during the Opium Wars" by a Chinese academic who observed that "this time, though, ‘gunboat diplomacy' could not work".

Such reactions are part of the uniqueness of China's story, observes Lovell. "I think nationalisms all over the world tend to define themselves negatively — namely, against a common enemy," she says. "What is unique about China is the way in which opinion-makers dwell on ‘national humiliation' [rather than more positive struggles and achievements] as a key experience in the Chinese nation between 1840 and 1945. There are books, museums, monuments and films on the idea. India, for example, which has a deeper experience of colonialism, does not have museums of national humiliation," she says.

But the takeaways from the Opium Wars get far more uncomfortable on the other side of the Pacific. There is the West's association with contraband narcotics trade, to start with — a trade that begins with the dawn of civilisation in Mesopotamia, is introduced to Persia and India by Alexander the Great, is monopolised by the East India Company for the lucrative Chinese market, thanks to its stranglehold over the opium growing districts of Bengal and Bihar, and is used as a barter by European and American merchants with Chinese traders to shore up silver reserves of the West, before being used to set up a global whirlpool of addiction patronised by rock stars and terrorists alike. Popularised by British Romantics such as John Keats and Elizabeth Barret Browning, opium — and heroin, in turn — has sapped the life out of talents ranging from from Janis Joplin to River Phoenix to Kurt Cobain to John Belushi.

"The contraband narcotics trade has thrived through, and contributed to, the political instability that has afflicted countries such as Afghanistan over the past 50 or 60 years," Lovell says. "It's an uncomfortable legacy for the British to be associated with. To be frank, the British are not conscious enough of their opium-trading past in countries such as China and India. This is a history that still has powerful resonances for contemporary global politics. In Britain today, our role in the opium trade and in the Opium Wars is largely forgotten. In our busy imperialist 19th century, the perception perhaps is that the Opium Wars were a sideshow, relative to our exploits in India, say, or Africa," she says.

Cut to a different time, a different stage — Iraq, perhaps, or Libya — and substitute opium with oil, and it is not difficult to see why Lovell says the Opium Wars are more than a mere piece of history in the theatre of global politics and business today. Or consider the "honourable" justification of opium trade and compare it to the unbridled greed and avarice of the banking industry that is blamed for triggering a global recession. "To understand China's troubled relationship with the West today, you have to understand how and why China remembers the Opium Wars, and Britain's role in these conflicts," she says.

As China and the West meander along in an uneasy global partnership — or sometimes the lack of it — Lovell sees hope.

"Although the West's historical crimes against China loom large in Chinese consciousness and although since the 1990s the country has experienced periodic eruptions of anti-Western nationalism, the country is assuredly now more open to international forces, and more globalised and cosmopolitan, than at any point in its past," she says.

More than 170 years after the theatre of the great Opium Wars was abandoned, the essence of the battle continues unabated between different nations and on different stages — as the archetype of an opportunist barter gone wrong. It no longer involves gunboat diplomacy but finds more sophisticated ways of execution — in the hunt for oil by global giants, in businesses scouting new markets for expansion and perhaps in the prison cells of Urumqi, where one Akmal Shaikh spent his last night on Earth.

3,400BC: Opium poppy is cultivated in Mesopotamia. The Sumerians call it Hul Gil, the "joy plant". They will soon pass along the plant to Assyrians, who will pass it on to Babylonians. The habit is then transferred to Egyptians.

1,300BC: In the capital city of Thebes, Egyptians begin cultivation of opium grown in their famous poppy fields.

460BC: "The father of medicine", Hippocrates, dismisses the magical attributes of opium but acknowledges its usefulness as a narcotic and styptic in treating internal diseases and epidemics.

330BC: Alexander the Great introduces opium to the people of Persia and India.

AD400: Opium from Egyptian fields is first introduced to China by Arab traders.

1,200: Ancient Indian medical treatises describe the use of opium for diarrhoea and sexual debility and describe the medical properties of opium.

1500: The Portuguese, while trading along the East China Sea, initiate the smoking of opium. China considers the practice barbaric.

1527: Opium is reintroduced into European medical literature by Paracelsus as laudanum and prescribed as painkillers.

1600s: Residents of Persia and India begin consuming opium mixtures for recreational use. Portuguese merchants carrying cargoes of Indian opium through Macao direct trade flow into China.

1601: Ships chartered by Elizabeth I are instructed to purchase the finest Indian opium and transport it back to England.

1637: Opium becomes the main commodity of British trade with China.

1700: The Dutch export shipments of Indian opium to China and the islands of South East Asia; the Dutch introduce the practice of smoking opium in a tobacco pipe to the Chinese.

1729: Chinese emperor Yung Cheng issues a decree prohibiting the smoking of opium and its domestic sale, except under licence for use as medicine.

1750: The British East India Company assumes control of Bengal and Bihar, the opium-growing districts of India.

1773: The British East India Company assumes monopoly over all the opium produced in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa.

1796: Import of opium into China becomes a contraband trade. Silver is smuggled out to pay for smuggling opium in.

1799: China’s emperor Kia King bans opium completely, making trade and poppy cultivation illegal.

1803: German scientist Friedrich Serturner discovers the active ingredient of opium by dissolving it in acid and then neutralising it with ammonia. The result: morphine.

1819: British poet John Keats and other English Romantics experiment with opium intended for strict recreational use.

1827: E Merck & Company of Darmstadt, Germany, begins commercial manufacturing of morphine.

1830: Jardine-Matheson & Company of London inherit India and its opium from the British East India Company.

March 18, 1839: Lin Zexu, imperial Chinese commissioner in charge of suppressing the opium traffic, orders all foreign traders to surrender their opium. In response, the British send expeditionary warships to the coast of China, beginning the First Opium War.

1842: The Chinese are defeated by the British in the First Opium War. Along with paying a large indemnity, Hong Kong is ceded to the British; the Treaty of Nanjing is signed.

1856: The British and French renew their hostilities against China in the Second Opium War. In the aftermath of the struggle, China is forced to pay another indemnity. The importation of opium is legalised.

1874: English researcher C.R. Wright first synthesises heroin by boiling morphine over a stove.

1878: Britain passes the Opium Act with hopes of reducing opium consumption.

1895: The Bayer Company in Germany begins production of diacetylmorphine and coins the name "heroin". Heroin will not be introduced commercially for another three years.

1903: Heroin addiction rises to alarming rates.

1905: US Congress bans opium.

1906: China and England finally enact a treaty restricting the Sino-Indian opium trade. Several physicians experiment with treatments for heroin addiction.

1909: The first federal drug prohibition is passed in the US outlawing the import of opium.

1910: After 150 years of failed attempts to rid the country of opium, the Chinese are finally successful in convincing the British to dismantle the India-China opium trade.

1923: The US Treasury Department’s Narcotics Division (the first federal drug agency) bans all legal narcotics sales. With the prohibition of legal venues to purchase heroin, addicts are forced to buy from illegal street dealers.

1925: In the wake of the first federal ban on opium, a thriving black market opens up in New York’s Chinatown.

Early 1940s: During the Second World War, opium trade routes are blocked and the flow of opium from India and Iran

(formerly Persia) is cut off. Scared of losing the opium monopoly, the French encourage Hmong farmers to expand opium production.

1950s: To maintain their relationship with Asian warlords in Laos, Thailand and Myanmar, while continuing to fund the struggle against Communism, the US and France supply them with ammunition, arms and air transport for the production and sale of opium. The result: an explosion in the availability and illegal flow of heroin into the US and into the hands of drug dealers and addicts.

1962: Myanmar outlaws opium.

1965-1970: US involvement in Vietnam is blamed for the surge in illegal heroin being smuggled into the US.

1972: Heroin exportation from South East Asia’s Golden Triangle, controlled by Shan warlord Khun Sa becomes a major source of raw opium in the profitable drug trade.

July 1, 1973: US president Nixon creates the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) under the Justice Department to consolidate virtually all federal powers of drug enforcement in a single agency.

1978: The US and Mexican governments find a means to eliminate the source of raw opium — by spraying poppy fields with Agent Orange.

1992: Colombia’s drug lords are said to be introducing a high-grade form of heroin into the US.

1993: The Thai army with support from the DEA launches its operation to destroy thousands of acres of opium poppies from the fields of the Golden Triangle region.

1999: Bumper opium crop of 4,600 tonnes in Afghanistan. United Nations Drug Control Programme estimates about 75 per cent of world’s heroin production is of Afghan origin.

2000: Taliban leader Mullah Omar bans poppy cultivation in Afghanistan.

Autumn 2001: War in Afghanistan; heroin floods the Pakistan market.

October 2002: UN Drug Control and Crime Prevention Agency announces that Afghanistan has regained its position as the world’s largest opium producer.

October 2003: The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the DEA launch a special force to curb surge in internet sales of narcotics from online pharmacies.

September 2004: Singapore announces plans to execute a self-medicating heroin user, Chew Seow Leng. Consumers face a mandatory death sentence if they take more than 15 grams of heroin a day.

May 2006: In Mexico, Congress passes a Bill legalising the private personal use of all drugs, including opium and all opiate-based drugs. Then president Vicente Fox promises to sign the measure but buckles a day later under US government pressure.

September 2006: The UN Office on Drugs and Crime reports that Afghanistan’s harvest in 2006 will be about 6,100 metric tonnes of opium — a world record. This figure amounts to nearly 92 per cent of global opium supply.

-Compiled from agencies