Luis Vazquez/©Gulf News

Vaddey Ratner calls each of the three parts of her tenaciously melodic second novel a movement. And indeed this story of an orphaned Cambodian refugee’s return to her homeland does have a symphony’s elevating effect on emotion. Ratner stirs feeling — sorrow, sympathy, pleasure — through language so ethereal in the face of dislocation and loss that its beauty can only be described as stubborn.

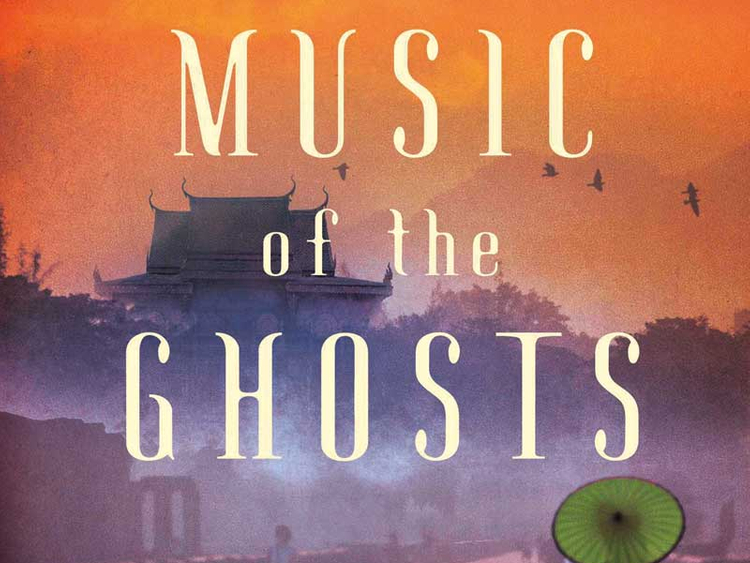

Music Of The Ghosts |

By Vaddey Ratner, Touchstone, 324 pages, $26 |

Music of the Ghosts is an aesthetic gesture akin to the plaintive playing Ratner’s protagonist, Suteera, hears in the novel’s third movement while walking through a forest near Angkor’s ancient temples. In a remote clearing, she finds an unlikely ensemble, the victims of land mines: a blind man, a fisherman, an amputee, a former Khmer Rouge insurgent and a former government soldier, rivals in another life now joined in making otherworldly music. The three-stringed instrument whose lament transfixes Suteera has only one string that still works. Both the musicians and their instruments are broken, disfigured, yet still they create beguiling art.

They also provoke an unsettling memory. Once before, in that very region, Suteera had heard the quiver of a string plucked in the wild. Then she and her aunt were fleeing Cambodia through an abandoned rice field sown with corpses and mines. Everyone else in her family was dead — except for her father, whose fate she did not know. Just before a mine exploded, claiming most of their escaping party, they heard a faint cry, resembling the sound of a lute. A little later, Suteera thought she heard it again. But when she told their captor turned saviour, the Khmer Rouge soldier who guided them across the Thai border, he dismissed it as hallucination. “Out here,” he proclaimed, “there’s only music of the ghosts.”

Such echoes haunt Suteera’s journey when she travels from her new home in Minneapolis to the Buddhist temple where her father had been raised by monks. Ostensibly there to scatter her aunt’s ashes, she has been lured by a letter from a guilt-stricken man who calls himself the Old Musician and claims that he met her father in one of Pol Pot’s prisons. He also claims to have three classical instruments owned by her father and intended for her. Suteera returns half-hoping to find her soldier saviour as well as her father, half-thinking the musician might in fact be her father. As the novel shifts between past and present, from her perspective to that of the Old Musician, another set of instruments emerges as symbolic: electric cords with exposed wires, metal clamps, pliers, a rope, all hung on the wall of the prison. One set of instruments is the dark twin, the reverberation, of the other.

Ratner’s book is full of doubles: two musicians; two sets of lovers; two father-daughter pairs; two orphaned girls; two poor, gifted boys with patrons. There are even two moons, seen when the Old Musician, making his way to an insurgent camp, comes upon a mosque and sees the carved crescent of its minaret in the aureole of an actual full moon: “He’d journeyed into a landscape ... where a self could exist both as a fragmented sliver and as a complete whole, not contradictions but inverted reflections of the same truth.” In that landscape, the author — a survivor of the Khmer Rouge regime who fled Cambodia not knowing her father’s fate — finds her doppelganger in her main character.

The novel’s ultimate inverted reflections are art and war, a pairing made explicit by a flashback involving the Old Musician, seen as a student at the school in postindependence Phnom Penh where the young Pol Pot taught French literature. As his students argue over the legitimacy of learning in the language of their ex-colonizer, the future dictator recites a line from Rimbaud’s “Guerre”: “I contemplate a war of justice or force, of unforeseen logic. It’s as simple as a musical phrase.”

Here, as in her debut novel about Cambodia’s genocide, In the Shadow of the Banyan, Ratner forges many musical phrases from conflict. The Mekong River is “a long, sinuous shroud, boats and sampans swaying on its surface like ornaments tentatively fastened to a tapestry.” Army tarps hung from branches are like “the wings of giant bats at rest.” The tips of rocket-propelled grenades are “half plunged into the earth like banana flower heads pitched from a great height by some immortal strength.”

“Art from war,” says the man who gives the Old Musician the pick he uses to pluck his instrument. It was made from a bullet casing by a woman who lost half her face in an acid attack. A wind chime given to Suteera at the novel’s close has been recycled from a gun. Music of the Ghosts has itself been fashioned by a writer scarred by war, a writer whose ability to discern the poetic even in brutal landscapes and histories may be the gift that helped her reassemble the fragments of a self and a life after such shattering suffering.

–New York Times News Service

Gaiutra Bahadur is the author of Coolie Woman.