Ramachandra Babu/©Gulf News

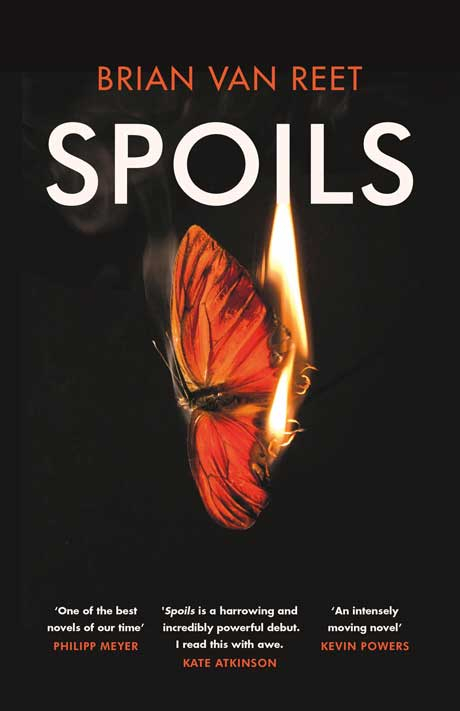

Spoils |

By Brian Van Reet, Jonathan Cape, 272 pages, £12.99 |

Brian Van Reet’s assured debut novel begins with one of the best opening chapters I’ve read for ages. The setting is Iraq, 2003, and we’re in a Humvee with three US soldiers as they come under attack. Van Reet makes the moment extraordinarily fresh through the vigour of his writing and his constant turn towards unexpected and intense detail. The scene takes place at night, in pouring rain; the muggy interior of the Humvee is “hot and slimy as a locker room”; and our protagonist, Specialist Wigheard, underslept and wired on diet caffeine, is a woman.

The strengths of this excellent book are all on show in these tight 15 pages: the vivid observation, the nuance of its characters, the deep familiarity with the processes of waging war. In 19-year-old Cassandra Wigheard, from the poor white underbelly of America, the book has a heroine who is both vulnerable and gung-ho, resentful of the protectiveness her commanding officer shows towards her and highly attuned to his weaknesses. She worries that the family photograph he has taped to the dashboard of the stuffy military truck – “continually reminding him of the stakes” – will weaken his courage.

Van Reet, a decorated former soldier who served as a tank crewman in Iraq, clearly knows this world. The contents of the ready-to-eat meals, the struggle to keep weapons free of sand, the needle-sharp pain of shrapnel wounds, the messy business of maintaining discipline over a horny army of near-adolescents – all are evoked with an exactness and rough poetry.

When Wigheard and her two comrades-in-arms are captured by an Islamist militia – becoming the spoils of the title – their predicament is described with the same beady eye. And though Wigheard suffers the nightmare of captivity in a lightless cell and the impending prospect of execution, her relationships with her captors are still drawn with nuance and dark wit. Alongside terrible cruelty, there is tenderness, and an almost comic revulsion when she gets her period. “Later I bring the insanitary pad,” says one worried guard.

Van Reet doesn’t flinch from skewering the invasion’s cruelty and ineptitude, but his ambition goes beyond presenting us with only the US experience. The story gives us three perspectives on the unfolding action: Wigheard’s, told in the third person, deals with the progressively mounting horrors of her captivity. This alternates with the first-person accounts of a tank crewman called Sleed who participates in efforts to rescue the captured soldiers, and that of Abu Al Hool, one of the leaders of the organisation that is holding them.

Al Hool is a middle-aged Egyptian who began his career with the Afghan insurgents fighting the Soviet army in Afghanistan. From a background of relative affluence – he recalls family holidays to Europe – he is increasingly troubled by the direction of the militia he’s part of. Led by the implacable Dr Walid, they are morphing into a proto-Islamic State, with the same appalling machinery of filmed executions. Al Hool’s storyline allows Van Reet to broaden the book’s scope, to humanise the Islamists, and reflect on the origins of their movement.

It feels intellectually responsible for Van Reet to push beyond the world he knows to give us a larger perspective on the war, but Al Hool is an empathic stretch for the author and there is more obvious contrivance about this section of the book. The plot requires a change of heart in him that never entirely convinces, and the self-consciously literary register in which he speaks sometimes seems to belong in a different novel. “I am only of middling ruthlessness,” he says at one point. “The oubliette is named for good reason and represents one of the prime truths of confinement,” he declares elsewhere, sounding like an Egyptian Severus Snape.

It is especially noticeable because the novel’s other voices are so convincingly natural. Sleed, the other first-person narrator, shares his experiences of tank warfare with a disarming plainness. An M1 Abrams, he says, “drives like an old Cadillac, one of those big boats from the 70s”; but he cautions against trying to cross a ditch in one. “The tank is so long, it’ll pitch down the slope if the sides are steep enough and get stuck in the bottom like a lawn dart.” Sleed is inessential to the plot, but his sections grip for other reasons. His comrades’ search for spoils of the material kind leads to a night-time foray into one of Saddam’s bombed-out palaces. This passage, like many of the book’s best moments, is rendered so clearly I felt as though I were watching it on a virtual reality headset. Elsewhere, as he muses on the difficulty of telling the story of the war fairly, Sleed seems to speak for the author as he channels the commonsense poetry of Huckleberry Finn. “There’s a certain way of doing it where the good guys become bad and the bad good, and there’s another way that I wish I could do where there are no categories.”

By coincidence, I read Spoils at the same time as the new translation of Boys in Zinc, Svetlana Alexievich’s oral history of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan – the conflict that first blooded the fictional Al Hool. Both accounts have a similar compelling energy, one that is generated by the painstakingly observed detail of lives lived in exceptional circumstances. Both bear eye-widening witness to valour, horror, violence, cruelty and absurdity. It is eerie and somewhat disheartening to find so many parallels between them. It may not be news that war is hell, but our chronic forgetfulness of the fact makes Spoils feel not only rewarding but necessary.

– Guardian News & Media Ltd

Marcel Theroux’s Strange Bodies is published by Faber.