Gorbachev: His Life and Times

By William Taubman, Norton, 852 pages, $39.95

Near the end of William Taubman’s superb new biography of Mikhail Gorbachev, the author describes the Russian president and his wife, Raisa, vacationing at Foros on the southern tip of the Crimean Peninsula, strolling along the shoreline just days before the failed coup attempt of 1991. As had been their habit for many years, their walks were marked by lively conversation. They debated: Are political leaders shaped more by personality or circumstances? They decided that leaders ride history like a tiger, and that it brings out the best in people. “Situations elevate leaders,” they concluded, according to Taubman, “often turning traits that ordinarily look like weakness into strengths.”

This is the essential question about Gorbachev and the momentous history he made. How did it happen that a peasant son of a remote province in the Soviet Union who arrived at Moscow State University “looking and sounding like a country bumpkin,” who became a regional Communist Party boss, a protege of KGB chief Yuri Andropov, and who “kept bookmark-filled volumes from Lenin’s collected works on his desk” would lead the Soviet Union over the precipice, end the Cold War and vanquish the very Communist ideology he so diligently studied in Lenin’s books?

The answer is woven through the pages of this enlightening biography. Taubman, professor emeritus of political science at Amherst College, and the author of a Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Nikita Khrushchev, devotes a full third of this work to Gorbachev’s early years, and with great skill lays bare the evolution that was so important to his later actions. Taubman shows that as he rose through the ranks, Gorbachev harboured profound doubts about all he saw, culminating, upon taking office in March 1985, in his declaration to Raisa during another stroll: “We just can’t go on living like this.” Gorbachev was a juggernaut, an unseen agent of radical change sneaking up on the calcified Soviet Politburo. But his intent was not to destroy. He thought he could save the Soviet Union and make socialism great again. In Taubman’s hands, the journey is an extraordinary story of one man and history in a tense wrestling match. The man wins by losing.

Gorbachev, from his youth, saw the giant gap between Communist Party slogans and the poor living conditions and repressive environment of everyday life. His freshman classmates at Moscow State University may have sneered at the country bumpkin who wore on his lapel the coveted “Order of the Red Banner of Labor” he earned in five summers of helping his father run a mammoth combine harvester, but Gorbachev also knew, better than they, that Stalin’s collectivization had left the countryside a disaster.

Later, in his first party job, he wrote to his future wife that local bosses were “disgusting” in the way they behaved: arrogant, impudent and conventional. As a regional party boss himself, he was shocked by the sight of a remote village, Gorkaya Balka, or Bitter Hollow, made up of “low, smoke-belching huts, blackened dilapidated fences” and asked, “How is it possible, how can anyone live like that?” Still later, Gorbachev joined a Soviet delegation visiting Czechoslovakia after Soviet troops crushed the Prague Spring in 1968. In Brno, factory workers turned their backs on him, and the lesson he drew was that Moscow’s use of force had solved nothing. Gorbachev began to question the massive over-centralisation of the Soviet system. The doubts spilled over, too, during a visit to Canada in 1983, when Gorbachev threw caution to the wind and, during a break, strolled in an orchard with Alexander Yakovlev, then the Soviet ambassador to Canada, sharing his deepening concerns. Yakovlev would become an architect of Gorbachev’s new thinking.

Gorbachev carried these doubts into power as Soviet general secretary and later president, pioneering earth-shattering reform, yet navigating the politics ever so gingerly, trying not to offend the hard-liners, yearning for still more rapid and radical change, and frustrated that he didn’t really know how to achieve it. Taubman portrays Gorbachev as a visionary determined to “go far,” a leader with “innate optimism and self-confidence, a substantial intellect,” and a strong desire to prove himself, but also a gradualist undermined by his own initial uncertainty and unwillingness to abandon the Soviet system.

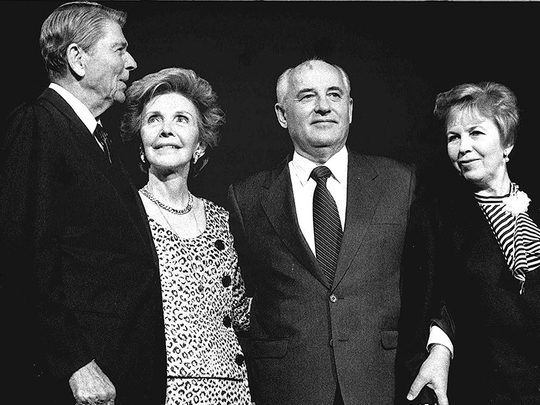

Time and again, Gorbachev’s radical intentions were underestimated. When he told Eastern European leaders in 1985 that he was not going to impose Moscow’s dictates on them — a remark that grew out of his disgust with the Prague Spring and his aversion to the use of force — they simply didn’t get it. Taubman says the Warsaw Pact leaders “went away convinced that he would not abandon them, but rather rescue them from the holes they were digging for themselves.” Gorbachev meant what he said, and four years later, he did not rescue them as the Berlin Wall collapsed and took them with it. Similarly, when Gorbachev proposed in January 1986 liquidating all nuclear weapons by the turn of the century, he was repeating what had been Soviet propaganda for many years, and it was dismissed as just that. But Gorbachev “took it seriously,” Taubman says, and pressed to sweep President Ronald Reagan off his feet at the next summit. In October, he did just that at Reykjavik. Although many at the summit thought it was a failure — myself included — because of the impasse over Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative, Gorbachev realised it was the first step towards braking the nuclear arms race.

At home, Gorbachev opened the stale, closed Soviet system. In 1989, a new legislature, the Congress of People’s Deputies, was chosen in the first relatively free elections since the Bolshevik Revolution. Gorbachev ordered the parliament’s proceedings to be televised, and the nation was transfixed by open debate and criticism. But Gorbachev’s breathtaking changes let loose all kinds of centrifugal forces beyond his control, including a yearning for independence among some Soviet republics. Taubman also shows the debilitating effect of Gorbachev’s rivalry with the brash Boris Yeltsin. In retrospect, Gorbachev did not go far enough. He should have broken with the party, abandoned the old guard, and independently set out to build a social democracy. His unwillingness to do so left him on the deck of a sinking ship.

The core of the rot in the Soviet system was the economy, but Gorbachev mustered only half-measures and could not make the leap to capitalism, backing away from Grigory Yavlinsky’s “500 Days” plan for a transition to market. Taubman does not dwell on it, but one of the most remarkable changes of the Gorbachev era, still recalled today, were the cooperatives, the first private businesses, from which the Yeltsin-era oligarchs got their early taste of profit. (Full disclosure: I shared some research materials with Taubman, and we once attended a conference with Gorbachev in Moscow.)

For all his weaknesses, Gorbachev opened a path to democracy for tens of millions of people, eased a Cold War that locked the globe into confrontation for four decades and shattered Soviet Communism in the land where it was born. In his superb summary, Taubman asserts, “The Soviet Union fell apart when Gorbachev weakened the state in an attempt to strengthen the individual.” Gorbachev’s accomplishments and his struggle are not appreciated today in Russia or the former Soviet republics. But someday, perhaps, a statue will be built to honour a country bumpkin who rose to the moment in history, and shoved totalitarianism into the grave.

–Washington Post

David E. Hoffman is a former Moscow bureau chief for the Washington Post, and author of The Billion Dollar Spy: A True Story of Cold War Espionage and Betrayal.