By Jennifer Egan, Scribner, 438 pages, $28

One definition of a great novel, William Styron said, is that it should “leave you with many experiences, and slightly exhausted at the end. You live several lives while reading it.”

Jennifer Egan’s immensely satisfying fifth novel, Manhattan Beach, the follow-up to A Visit From the Goon Squad (2010), which won a Pulitzer Prize, has a good deal of that kind of life-swamping and life-supplementing effect.

It’s a dreadnought of a Second World War-era historical novel, bristling with armaments yet intimate in tone. It’s an old-fashioned page-turner, tweaked by this witty and sophisticated writer so that you sometimes feel she has retrofitted sleek new engines inside a craft owned for too long by James Jones and Herman Wouk.

This novel has overlapping stories that, like tugboats, nudge one another into harbour. Most fundamentally it tells the story of Anna Kerrigan, a young woman who works during the war at the Brooklyn Naval Yard, where women have been allowed to hold jobs (welders, lathe operators, machinists) that had belonged only to men before many of them went off to fight.

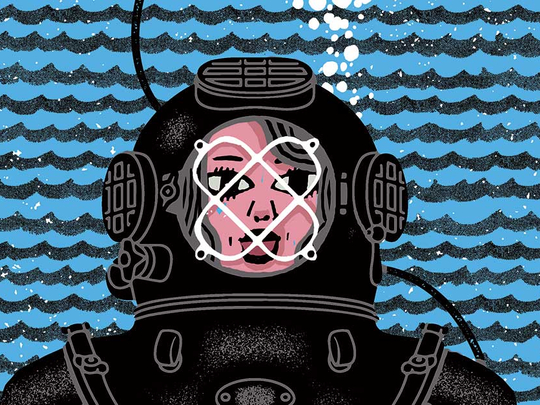

Over the course of Manhattan Beach, Anna becomes one of the military’s first female divers. This novel throws open many other worlds. Anna’s father, Eddie, a union man down on his luck, becomes involved in the wartime financial underworld and disappears.

One of the men Anna’s father mingled with, a complicated gangster and nightclub owner named Dexter Styles, who wants to go legit, moves sideways into Anna’s life. She begins to comprehend who her father was, and what might have led him to vanish.

This ostensibly traditional novel is not, perhaps, the book we expected from Egan. A Visit From the Goon Squad, set in the music world, was a jittery slice of modern urban life. It made your eyes pop out of your skull, as if you were a prawn, or you had done three fresh lines of white powder. It was unafraid of narrative fripperies. One chapter was told in the form of PowerPoint slides.

One reason that earlier novel branded itself upon your mind was that Egan clearly knew so much about how music gets made and sold. Her handle on how things work is just as present in Manhattan Beach. She is masterly at displaying mastery.

How to search for a body underwater, how to facilitate your rescue if lost and drifting at sea, how to run a nightclub, how to bribe a cop, how to care for an invalid - you learn things while reading this novel. Egan’s fiction buzzes with factual crosscurrents, casually deployed.

This is a sea novel, one that is consistently aware of Manhattan as an island. Reading Edna O’Brien’s short stories, there’s nearly always a fire blazing in the background. In Manhattan Beach, nearly every scene is set against a river or an ocean or a tidal pool.

Water here is a place of rebirth and of mortal terror. Early in the novel, as Anna watches the sea, Egan writes: “There was a feeling she had, standing at its edge: an electric mix of attraction and dread. What would be exposed if all that water should suddenly vanish? A landscape of lost objects: sunken ships, hidden treasure, gold and gems and the charm bracelet that had fallen from her wrist into a storm drain.” There are dead bodies down there, too, Anna’s father tells her, in lines that ring like a premonition.

Anna goes to work at the Naval Yard, her eyes always flickering toward the ships in the water outside the factory windows. This novel has a bustling sense of war-work and women’s place in it. Dexter is given a look at this ferment, and he reports:

“Eight hundred girls worked inside Building 4, a structural shop, their last stop. It was hard to separate them from the men - the welders especially, with their thick gloves and face shields. You had to go by stature, and as their group moved from bay to bay, Dexter got better at this. Girls holding blowtorches. Girls cutting metal into pieces; girls building molds of ship parts from wood. A matter-of-factness about even the pretty ones; em>look or don’t look/em>.”

Egan is a generous writer. She doesn’t write dialogue, for example, so much as she writes repartee. Many writers’ books go slack when their characters open their mouths, as if dullness equals verisimilitude. Egan’s minty dialogue snaps you to attention.

Anna reads mystery novels, and this novel itself becomes a kind of noir thriller. Egan is aware of the bad luck and missed opportunities that can drive men and women toward crime.

She’s aware too of the class element that can be involved. Dexter marries into a prominent family, but can’t shake the sense that he’s tainted. He looks at his wife’s father and thinks: “The Berringers were wearing top hats to the opera when Dexter’s people were still copulating behind hay bales in the old land.”

The biggest mystery is Anna herself. The war has shaken society loose, she realizes. If she can be who she wants to be, what form should her life take? The search for answers to that question will lead her across the country, where she will gaze at a different ocean.

If I have a complaint about “Manhattan Beach,” it’s that while Egan is in full command of her gifts, there’s only rarely a sense that she’s pushing herself, or us. This novel is never estranging. It never threatens to overspill its levees, or to rip us far from shore and leave us there for a while.

Egan works a formidable kind of magic, however. This is a big novel that moves with agility. It’s blissfully free of rust and sepia tint. It introduces us to a memorable young woman who is, as Cathy longed to be again in “Wuthering Heights,” “half savage and hardy, and free.”

–New York Times News Service