On the stage, a comedic villain twirls his moustache and scowls with unconvincing menace; a skimpily clad damsel is manacled to a wall — but still manages to flirt with the audience.

The audience in the theatre laughs (a little) or sit wreathed in cigarette smoke, many talking among themselves.

All this in silence. A silence which is shattered by a discordant blast of brass and drums loud enough to drown the tears at an Iranian funeral. For that, in effect, is what this scene is heralding; the black and white images of the acting troupe are replaced by stark bleached-out news photos of the theatre seats, burnt to charred matchsticks by a horrific fire.

The film is barely two minutes long but it relates to one of the most traumatic events in Iran’s recent history — the arson attack on the Cinema Rex in Abadan, southern Iran, in which more than 400 people were killed. It happened on August 19, 1978, and the tragedy, which is considered to have been perpetrated by radical militants, helped to trigger the revolution of 1979 which overthrew the Shah.

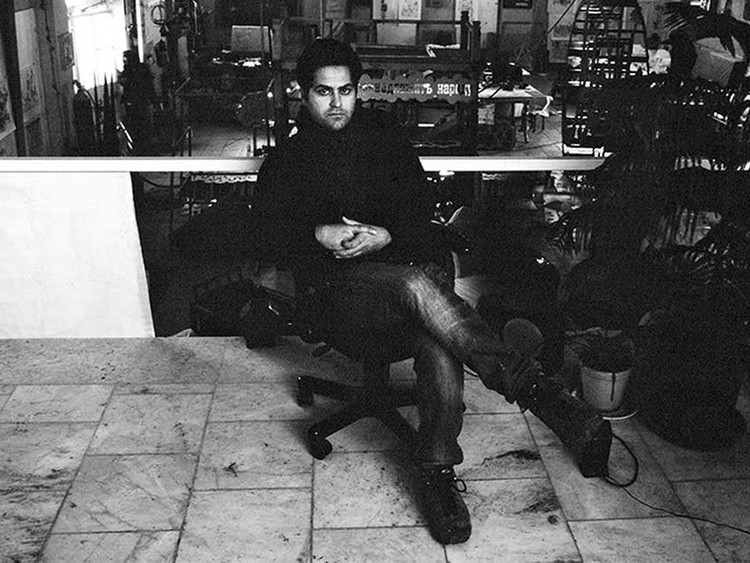

The effect of that terrible crime is examined by one of the country’s most uncompromising artists, Mahmoud Bakhshi, in “The Unity of Time and Place” at the narrative projects gallery in central London.

In the same show on a separate screen, there is an interview with one of Iran’s most radical film directors Masoud Kimiai, who in 1978 made one of the country’s best known films, “The Deers”. It is from that work that the cheerily over-the-top sequence is taken.

The two pieces by Bakhshi are more than a record of a terrible event. They are investigations into a society which has suffered its traumas and asks the question; what is the role of the radical artist in Iran and, indeed, anywhere in the world?

“We face agonising traumas, at any time and in any place,” says the artist. “I wanted to talk to Kimiai about the social and political role of the artist. I also wanted to question my own place. Which side do I take and how far I should go?”

“The Deers” highlights the plight of the poor and uneducated under the Shah’s regime in contrast to the wealth and privilege of the few. The significance of the stage scene is simply because it appears in the film after about 25 minutes — the time when the arsonists locked the doors of the cinema and set fire to it.

The people we see in the film’s theatre come to represent, in Bakhshi’s work, the original audience who seconds later will be swept away by flames.

“To me it was crazy moment,” he says. “The film showing people in the cinema was a mirror image of the real last moment. The people on the screen are actually people from that period and to me it was as if they were the same ones who were killed. That’s that why I projected the pictures of the burnt out seats on the skeleton of the cinema.

The title of the show refers to the connections and the coincidences of time and place which centre on the fire and which led to the transformation of not only Iran but the entire region.

The fire took place on the same day 17 years after the coup d’état of 1953 which had brought the Pahlavi dynasty to power. The coup started in the oil-producing city of Abadan which later became the centre of the Islamic Revolution’s own seizure of power in 1979 and in turn to the demise of the Shah. The following year Iraq invaded Iran and the countries spent the next eight years embroiled in a war which cost as many as one million lives.

“The fact that both of these catastrophes — the fire and the 1953 coup — were both on the same day was a kind of funny comparison,” says Bakhshi. “These are perhaps the two biggest key events in current Iranian history.

“Many art works were made around these subjects but few piece have affected society as much as “The Deers”. Kimiai was one of the most effective artists in Iran with his support for the lower classes and fighting for their rights against the Shah’s regime. In “The Deers” there is a guy who is killing the police, one character says: ‘We have to have to fight this regime, we have to kill.’ Kimiai is supporting anarchy. He was a radical before the revolution, though perhaps less now.”

Bakhshi decided to interview the director, who is now Iran’s head of TV and culture, to try to understand what it is like to be an artist ‘on the edge’.

The camera is held unflinchingly on Kimiai as he talks. He is moist eyed with emotion throughout. Again, there is no sound, instead captions on either side of his face record — and compare — the timeline of events. On one side the last moment of the 1953 coup which ends with 300 deaths and the burning down of the house of the democratically elected prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh; on the other the rising death toll of the cinema fire.

“My last question to him was about the fire,” says Bakhshi. “I tried to persuade him to talk but he was angry and tried to escape the questions. I insisted. He started talking then but he dropped out of view of the camera and asked not to have his answer recorded, which I duly honoured. The result is a kind of visual art. By erasing the voice you can see the emotion, you can see he was suffering. It is like a painting.”

To contrast the silence but dramatise the pain of the victims — and the discomfort of the director — the interview ends with the sound of pounding drums.

“The interview lasted for one hour and I tried to focus on the edge that you have to walk as a social and political artist,” says Bakhshi. “If you go in one direction or join one party you don’t walk on the edge any more. Where is this edge? What is the result, What do you feel?

“Kimiai did not even want to have the Islamic Republic to come into being but he was opposed to the Shah’s regime. As a political artist he had a critical point of view but the question is; how responsible are you as an artist afterwards? How do you feel with the results of your art? That’s the question I am trying to answer too.”

All of Bakhshi’s work relates to Iran and his own experiences in the country but he argues, there is a universal truth about his work — traumatic moments happen in all societies.

“People might say that the work is limited and local and it is true that not even next generation after me have any relation to those days but by presenting these facts from different periods of Iran’s history I try to show that the problems are always the same. Nothing really changes. That’s why I play with this. I find it quite crazy. Abadan is like an ongoing story, the coup and the fire are ongoing traumas. You can compare and apply this example to many places so it’s not just my crazy thoughts about my war, my place, my childhood, this is happening any place, any time. You can see this on Kimiai’s face as the two parts of the story come together in parallel.”

The intensity of the artist’s vision came to prominence in 2009 when he won the Magic of Persia Contemporary Art Prize and held a solo exhibition at London’s Saatchi Gallery.

His works included “Tulips Rise from the Blood of the Nation’s Youth,” in which eight sculptures with four crescents and a sword formed like a tulip, are bathed in a bold red light. He has taken the tulips, the symbol of the revolution which is seen everywhere in Iran on murals and posters commemorating the soldiers killed in the Iraq war and set them on a tinplate pedestal. They can be turned in a parody of the state’s ubiquitous propaganda and in so doing he questions the rhetoric of the regime which glorifies its martyrs but ignores the execution of the thousands who oppose it.

In “Air Pollution in Iran” he took eight shabby flags that had hung on official buildings and been dirtied by by Tehran’s notorious pollution. He says the flags also represent the dirty secret of mass executions of thousands of political prisoners by the government which took place over a few days in 1988 shortly before the end of the Iran-Iraq war.

Bakhshi was affected by the trauma of the war in which a family member died. No wonder his work is so committed, so political.

“I grew up with continual disasters,” says Bakhshi who was born in 1977. “The war started when I was three and ended when I was ten. So for me, everything is political. Iranian art and culture is so much about messages and literature.”

The 2002 work, “Thank You for Coming to Paradise,” is a striking example. He laid sheets of mirror glass on foam and invited people to walk on the surface.The glass was shattered, invoking an image of a paradise lost. He took the fragments and hung them on a wall and in a dramatic, maybe melodramatic, gesture, he kissed them leaving the blood from his lips on the glass.

“I was young,” he says dismissively

He has attempted to make less overtly contentious works. In “Rose Garden” he took a photo of a flower every night for four months. The result is 64 post cards with the name of the flower, date and place of photography. Each of the flowers represents the Islamic Republic’s desire to emphasise the beauty of their heritage - even if the reality is very different.

The postcards divide into eight - there were eight years of the Iraq War, and eight flags in “Air Pollution of Iran” and there are eight chairs in the gallery cinema. So even then, the prettiness of the postcards is not free of pointed symbolism.

Like most artists from the Middle East Bakhshi is faced with wary governments. In his own country, where the visual arts attract a small audience and are less influential than, say, cinema, the censorship is slight but he was banned by the UK government from attending his show in London.

“My visa was rejected two days before. To me it’s fine. Every time I do a show I have to go through a long process so I thought it would have made a good overture to display all the documents I had to fill in when applying for a visa. They would have made a nice opening at the entrance to the gallery.”

He is spared the ban in the Netherlands where has a showing at Art Rotterdam (February 9-12). One the subject of bans, how does he view the apparent hostility to Muslims by US President Trump? He is surprisingly relaxed about it.

“He has the same populist strategy as Ahmadinejad (Iranian politician president from 2005 to 2013) had at the beginning so we are familiar with that kind of behaviour. Though maybe he was not as rude about women.”

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.

The Unity of Time and Place runs at narrative projects in London through March 11.