Nick Bashall was born in England and grew up on a farm in Zimbabwe. He returned to the UK to study law at Cambridge, where he was also the heavyweight boxing blue. He also played cricket using his height to great advantage as a right-handed fast bowler. He began his career with a big solicitors’ firm in London, but just before his final law exams he had an accident that left his right arm paralysed and right leg badly injured. He was 26 years old then and the incident changed the course of his life.

Today Bashall is one of the leading portrait painters in England and has been commissioned by members of the British royal family and top brass from the British army. He is also well-known for his portraits of children, and for his live portrait painting performances at music festivals and other events. He has also travelled with the British army as a war artist, documenting its campaigns in Kosovo, Kabul and Iraq.

Bashall has a long association with Dubai. Soon after his accident in 1982, he came to the city to work for a British law firm and to save money to go to art school. He worked here for six years, and also taught art at the Dubai International Art Centre. Since then he has visited Dubai regularly, and exhibited his work at the Majlis Gallery.

He is here again and presented an entertaining live portrait painting performance at the Majlis Gallery last night. He will accept commissions for portraits, and conduct workshops at the Majlis Gallery throughout this month.

Bashall spoke to the Weekend Review about his work and his experiences as a portrait painter. Excerpts:

How did you decide to be an artist and especially a portrait painter after losing the use of your right hand?

I could always draw well but had never thought art could be a career. Sometimes, when I was bored during meetings at the law firm I would draw faces under the table, and I had started going to art school at night. I was returning on my motorbike from a cricket match, where I had taken nine wickets, when the accident happened. When I regained consciousness, I could not feel my right arm and the doctors were talking about amputating it, and I immediately knew that I would never be able to use it again. The first thing I did was to ask for pencil and paper and began sketching the man in the bed opposite me with my left hand. It just happened naturally, and the choice was made for me. Almost losing my life helped me to decide what was important to me.

What brought you to Dubai?

After 10 months in hospital I finished my exams and wanted to get back to work. It was hard for my body to recover in the cold, wet weather of London so I decided to get a job in the Middle East, where I could soak in the sun, swim in the sea and also make money to go to art school. When a friend in Dubai told me about Spanish maestro Joaquin Torrents Llado and his art school in Majorca, I just knew that he was the teacher for me because he was still teaching in the academic tradition that had been abandoned by the modern school of painting across Europe. I trained with him for five years and became a full-time artist in London in 1997.

Why do you paint from life rather than from a photograph?

Copying a photograph would be so boring. When the person is sitting in front of me for a few hours, I am reacting to them instinctively, sensing their personality, and feelings and unconsciously selecting the things that strike me. A portrait is a combination of different moods of the sitter. I try to get under their skin by keeping my mind clear and open to receive, and help them to relax so they can show me their most beautiful side. These paintings last for generations and I want those who see my portraits even generations from now to feel they know the person and can sense their character.

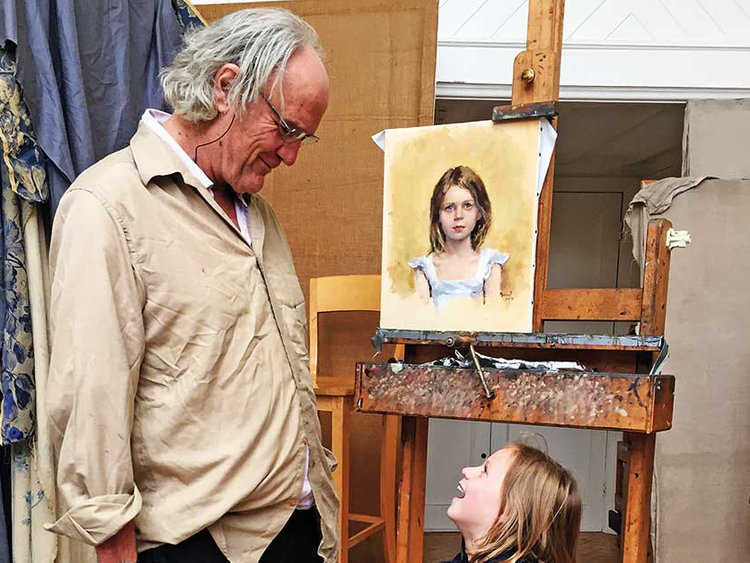

How do you get children to sit for so long?

Children are the best subjects because they do not care how they look and are so transparent. I always paint with a mirror placed behind me, so that my sitters can see the painting develop and feel part of the process. This works well with girls. With boys I have to be strict, but I try to make friends with them by playing games such as cricket with them.

In this age of ‘selfies’ why do people still want to sit for a portrait?

An oil painting lasts longer than a photograph, and there is something special about the fact that it is made by hand, and it is a continuum of an age-old tradition. In England this a strong tradition among the aristocracy and in the armed forces. Also, many parents want to have portraits of their children done, and people do it as birthday or anniversary gifts for spouses.

What is the idea behind doing painting performances in public?

This is my way of rebelling against the fact that today public taste is dictated by dealers, galleries, auction houses and art critics. At music festivals such as Glastonbury I set up a studio in a tent, where my students and I paint festival goers from life, in a party atmosphere complete with DJs. We want to show the art world that painting from life can be entertaining, skillful and good value. I also host such events in my studio.

What is the role of a war artist in our media dominated world today, and what were your experiences as one?

Traditionally the highest form of painting was history painting, which involved recreating famous wars, so having a war artist became a tradition in the army, and continues till today in the British army.

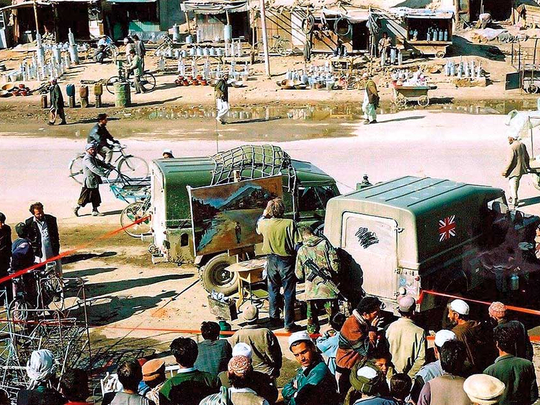

I was first invited to document an important event in London for the Parachute Regiment. Later when the regiment went to Kosovo the commanding officer asked me to come along and record their campaign. During sensitive meetings between the UN forces and the Kosovo Liberation Army, where photographs were not allowed, I stood in a corner and quickly sketched the scene, and later I painted portraits of all the officers of the KLA, which helped to break the ice between them and our forces. In Kabul, I painted in the streets, guarded by soldiers, with hundreds of curious onlookers around me, documenting the badly damaged city, and the gradual return to normalcy as shops opened and people began to come out on the streets. Documenting the British campaign in Basra in 2004 was much more dangerous, but I did go outside to paint scenes of the local souq.

What motivated you to take those risks?

It was an adventure, and this kind of raw painting was a good change from painting in the studio. I met some amazing people and saw some amazing places.

Do you paint a self-portrait every year like Rembrandt?

No, I do self-portraits only to experiment with colours and techniques.

Nick Bashall will be in Dubai until the end of the month. For information regarding commissions and art lessons contact Majlis Gallery at majlisgallery@gmail.com