Technology has become an essential part of the contemporary world. It has entered our daily lives in the form of communication and tracking devices, as well as systems such as those that enable electronic financial transactions. Our dependence on technology, coupled with our limited understanding of how it works, leads to a variety of anxieties and fears. The latest exhibition by The Art Gallery at NYU Abu Dhabi, “Invisible Threads: Technology and its Discontents” explores the “invisible threads” that bind us to modern technology, and contemplates our everyday interactions with technology, and the tensions emerging thence.

The show features 16 works by 15 artists from around the world, ranging from a computer programmed to paint like humans, to masks of human faces generated from DNA found on chewing gum; and from sculptures made from USB chargers to a working satellite that will be launched into space after the show closes. The artworks include new commissioned works by Monira Al Qadiri, Wafaa Bilal and Evan Roth, as well as key historic works by Ai Weiwei, Jamie Allen, Aram Bartholl, Taysir Batniji, Liu Bolin, Jonah Brucker-Cohen, Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Michael Joaquin Grey, Phillip Stearns, Siebren Versteeg, Addie Wagenknecht and Kenny Wong that have been borrowed from the artists, private collections and international art institutions.

The show is curated by Bana Kattan, assistant curator at NYU Abu Dhabi Art Gallery, and Professor Scott Fitzgerald, programme head of Interactive Media at NYU Abu Dhabi.

“Our gallery aims to address topics that are both globally significant and locally relevant, such as our increasingly dependent relationships with technology, a subject that affects us all. This exhibition explores the intersection between art and technology, but it is essentially about the emotions and feelings associated with our use of technology. Every piece we have included speaks about technology from a different perspective, and looks at the different ways in which it impacts humanity and our society,” she says.

Fitzgerald, who regularly runs workshops on using technology in the arts, is the first guest curator to be invited by the gallery as part of an initiative to involve scholars and specialists from across the academic spectrum in curating major exhibitions. “This has been a unique opportunity for me, especially as an extension of my academic work. The issues we are trying to address in the show are important as we try and situate ourselves in a new technological era,” he says.

The artists have found diverse and innovative ways to explore the theme. American artist Grey has created an exact 1:1-scale replica of the Russian satellite Sputnik. Placed at the entrance to the gallery, this reminder of the first manmade satellite that launched us into the information age is an apt starting point for the show, and a powerful metaphor for its theme.

Iraqi-American artist Bilal’s commissioned work is also a satellite, but a functional one, called Thumbsat. It is inspired by a rumour that the Iraqi space programme had planned to launch into space replicas of a sculpture of former Iraqi president Saddam Hussain. For this project, the artist has created a brass model of that sculpture, as well as a tiny 3D-printed replica of it that he has fixed on to his satellite, with a camera pointed at it. He plans to launch the satellite into space after the show closes, and viewers can log on to a website to follow its path until it re-enters the Earth’s atmosphere and is destroyed. The work draws parallels between the possibilities and pitfalls of technologies and political ideologies.

Chinese artist Liu and Wagenknecht, an American based in Austria, have both used materials associated with technology to create their artworks. Liu’s “Angels”, features hundreds of USB cables draped over sculptures of winged cherubs, as a manifestation of how the cables that carry data and power to our devices bind us, even as they lift us up. By stamping his name on the cables, the artist seeks to remind viewers that these tools are made by us, and our dependence on them is of our own making.

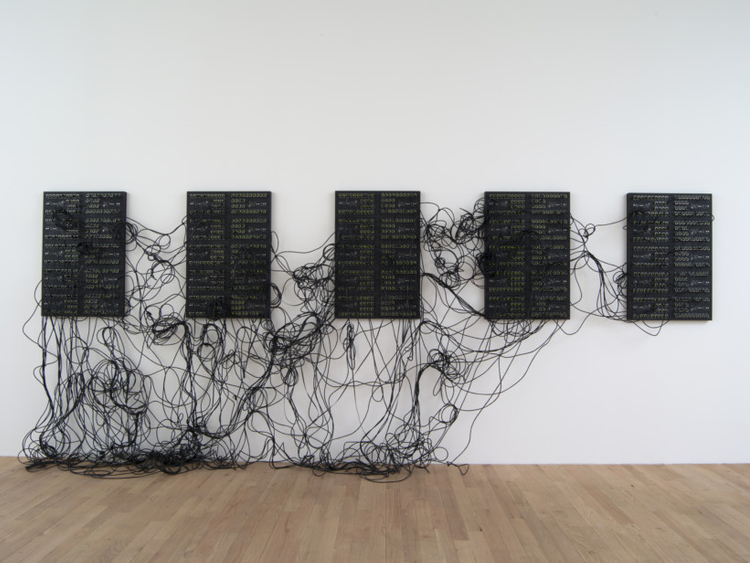

Wagenknecht’s “XXXX.XXX” attempts to expose a part of our daily use of technology that we cannot normally see. Her sculpture, made up of circuit boards and a network of cables, reveals network traffic via blinking lights, offering a moment in time where we can see the piece registering the Wi-Fi data travelling through the air, from one inbox to another. While the piece reveals the movement of information, it also exemplifies the “black box” effect of making information systems difficult to track and comprehend.

Hong Kong-based Kenny Wong’s interactive artwork, “Squint”, also taps into our fears of the unseen side of technology and the idea of technology that we have created being used in a way it was not intended to be used, and even against us. The piece is a wall of mirrors that attempts to reflect the light from the gallery into the viewer’s eye. The mirrors rotate in response to the position of viewers, creating a situation where the work sees them, and puts them in the spotlight, but as the light bounces off the mirrors it intentionally obscures itself from being seen.

Brucker-Cohen has used an unusual way to draw attention to the fact that as we increasingly dwell in the virtual world, we are losing touch with the natural and built environment around us. The American artist’s piece, “Alerting Infrastructure!” is a large hammer drill mounted on the gallery wall, which gets activated every time an online visitor enters the gallery’s website. By translating every online “hit” into physical damage to the gallery wall, the work literally connects the virtual world to the physical one.

Bartholl’s “Unknown Gamer” also highlights how technology makes us unaware of our surroundings through a series of images of people so engrossed in playing games on their phones that they were oblivious of being photographed by the German artist during his daily commute in Berlin. In an ironic gesture, he is also displaying the images to the public on a series of smartphones.

Evan Roth’s site-specific commissioned piece, “Scroll”, is a giant fingerprint swiping across the gallery wall in a gesture akin to the swiping of a touch screen. The Paris-based American artist’s work highlights the innately human way that we interact with digital devices. The fingerprint, which has been lifted off his own phone, plays on our fears of being exposed by technology. By scaling it up to a monumental size, Roth reminds us of the huge impact that even the most banal gestures have in today’s world, and that we leave behind traces of our identity in every interaction we have with technology.

Dewey-Roth has taken this idea and the fear associated with it further in “Stranger Visions” featuring an eerie collection of lifelike computer-generated 3D portraits, that could be anyone of us. She extracted DNA from items such as chewing gum, hair and cigarette butts that she found in public spaces, and used it to create renderings of what the people who left them might look like in the form of 3D printed masks. The work raises questions about the potential reach of this technology for identification, highlighting the fact that any trace we leave behind could possibly be a self-portrait.

Batniji’s “Pixels” is a series of portraits done by hand. They are based on images of blindfolded men taken from surveillance cameras, and the artist has used pencil on paper to make them look like low resolution pixelated digital images. The Palestinian artist sees this work as a 21st century portrait of Palestine, alluding to the idea that although technology provides us immediate information, it has distanced, desensitised and disconnected people from crises.

Famous Chinese artist and activist Ai’s contribution to the show is a digital print on wallpaper titled “The Animal That Looks like a Llama but is Really an Alpaca”. The print features golden representations of the Twitter icon intertwined with handcuffs and surveillance cameras as a warning about the double-edged sword of our “performances” on social media that expose details of our lives to friends and strangers.

One of the most interesting mixes of technology and art in the show is American artist Siebern Versteeg’s “Like”, which illustrates ways in which we teach technology to mimic ourselves and program it to relate to us. The artist has written an algorithm that allows the computer to make a painting. So, on one side of a screen is an image of the computer creating a painting in a very human-like way, and on the other side of the screen, the computer does a Google image search of its own painting to find the most similar image from its human-generated database. While writing the program the artist has taken into consideration details such as the viscosity of the paint and the ripples on the canvas when the paint is applied, and that the computer does not ever repeat the same painting. But he has then relinquished control to the machine to make the painting, and to Google to find the matching images, alluding to artificial intelligence systems, our illusory control of technology and the anxieties this evokes.

Kuwaiti artist Al Qadiri looks at the technology of oil exploration through her commissioned works that are scaled down replicas of oil drill bits made from plastic, an oil derivative. She has painted the sculptures with the iridescent colours that are shared by oil and pearls, thus linking the pearl diving-based economy of the past to the region’s current oil-driven economy. But there is also a layer of the future in these works as the artist imagines a scenario when the oil has run out, and the drill bits are exhibited in museums as relics from the past.

The show is complimented by a public programme comprising free talks, events and workshops for all ages. The next workshop, LittleBits will be held on December 12 from 4 to 6pm. It invites children aged eight and above and their families to learn how to use LittleBits, which are small, open source, modular electronics components that snap together with magnets to form larger circuits, to create electronics and artworks that light up, beep, spin and turn.

Jyoti Kalsi is an arts-enthusiast based in Dubai.

“Invisible Threads: Technology and its Discontents” will run at The Art Gallery at NYU Abu Dhabi until December 31. The gallery is located at the main entrance to NYUAD’s Saadiyat campus, and is open to the public from Monday to Saturday, noon to 8pm. For more information and to register for events, visit www.nyuad-artgallery.org