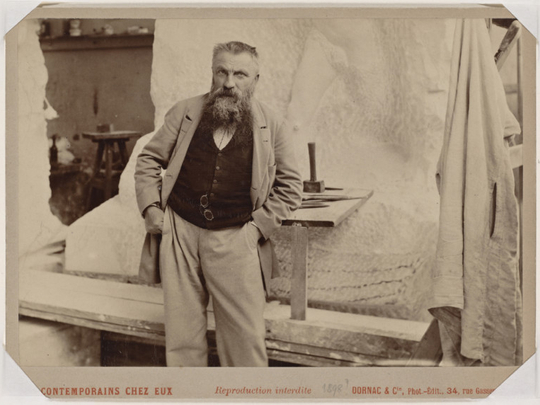

In his later years Auguste Rodin took to drawing nudes with “all the immediacy, force, and warmth of a life that had an almost animal quality”.

His private secretary, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, recalled how thousands of sketches “flew” from his hand, his pencil moving at lightning speed as his models wandered about unposed and natural — dressing, undressing, washing — relaxed enough to forget he was there and allowing him to capture the slightest nuances, the tiniest gestures.

One of sculptor’s favourite locations was the wood panelled rooms of the Hôtel Biron on the Rue de Varenne, in Paris, across the road from Napoleon’s Tomb in Les Invalides. He had been persuaded to rent a room in the summer of 1908 after Rilke had enthused: “My dear great friend, you should see this beautiful building and the room I have occupied since this morning. Its three bay windows open expansively on to an abandoned garden, where trusting rabbits can sometimes be seen leaping through the trellises like figures in an ancient tapestry.”

Now Hôtel Biron — better known as the Musée Rodin — has reopened after three years in a triumphant €16 million (Dh64.3 million) resurrection worthy of Rodin’s works with all their intensity, physicality and unquenchable creativity.

Hôtel Biron is a fine mansion built in 1732 for a wealthy wig maker and financial speculator but by the late 19th century, a group of nuns who ran a school for aristocratic girls in the building were forced to leave. While officialdom dithered over what to do with the building, it was rented out to a number of young artists, such as the painter Henri Matisse, the dancer Isadora Duncan and the poet Jean Cocteau for use as studios or lodgings.

Rodin agreed with Rilke about the beauty of the place and although he had a home and studio in Meudon, just outside Paris, and another studio in Dépôt des Marbres in the city itself he moved in a few weeks later, renting first one, then several rooms on the ground floor.

Gradually he acquired more rooms until in 1911 the authorities threatened the lodgers with eviction. Using his contacts — not to mention his prestige — he donated his collections, possessions and copyrights to the French state in 1916 as long as he could continue using the mansion as his “showroom”. He died in 1917, two years before it opened.

The museum has not undergone full renovation since that time. Today there is space for 600 works spread across 18 rooms as well as an $11 million (Dh40.4 million) restoration of the eight hectare gardens which surround the mansion. The rooms now have a lightness about them which was not there before — glass vitrines on simple bases have replaced a variety of solid plinths, heavy turntables, old-fashioned vitrines. Many of the dark wood panels, etched in gold, have been refurbished and the hard-worn parquet floor replaced.

Now it is possible circulate around the two floors without the way being blocked on the first floor by an office. Visitors had to trail back and start again.

You can get close to the works, walk around them. It’s hard not to touch.

Some of the rooms have been repainted from the white into what is dubbed Biron Gray — a marketing coup for English colour consultants Farrow & Ball who created the subtle shade which is designed to complement the works in bronze and marble.

Already blessed with natural light from the tall windows, the lighting alters automatically in reaction to the changes in light outside while still allowing the slightly weathered mirrors to add their own luminosity. More than 100 sculptures, such as “The Kiss”, have been cleaned for the first time along with 80 plasters and 50 paintings.

The power of Rodin is immediate the moment you step off the Rue De Varenne and into the courtyard.

In one direction, framed by top-shaped conifers is “The Thinker”, the Eiffel Tower and the golden dome of Napoleon’s tomb looming behind and at the other end of the garden, the “Gates of Hell”, the sculptor’s unfinished but mesmerising tumult of troubled souls inspired by Dante’s “Inferno”, the poem of the damned. The Burghers of Calais — six leaders of the city who were prepared to sacrifice themselves to save their countrymen from English invaders in 1347 — present their backs to the street but even from that angle still evoke their sacrificial anguish.

Follow the paths through the fading roses of autumn and chance upon Balzac, a monumental figure, proud, arrogant, draped in the monk’s habit he used to wear when writing. It caused such an outrage when it was unveiled in 1898 that the commission was cancelled and Rodin never saw his monument cast in bronze. The politest criticism was that it was a “heap of plaster”.

As one contemporary wrote “The Hôtel is only truly melancholic when, on misty days, it looks out on to the wilderness of the abandoned garden; it is only sad when it seems to evoke its past, with copses and little temples.”

The wilderness is tamed now but alongside the straight lines of the formal gardens to the rear a parade of linden trees, leaves fading and falling in the autumn, provide shade for statues such as figures who were to reappear in the Burghers of Calais and a monumental, sprawling, Victor Hugo.

Inside, the museum has been laid out in chronological order and in themes such as Public Monuments and Enlargement and Fragmentation, which examines the sculptor’s techniques. The early rooms contain busts which are evidently influenced by Michelangelo after a trip he made to Rome in 1875 but lack the raw physicality that characterise the works that made his reputation.

They also display his painting collection. Some surprisingly nondescript landscapes by the man himself and others, more impressive, by his contemporaries, such as “Le Père Tanguy” by Van Gogh, Edvard Munch’s 1907 painting of “The Thinker”, a Renoir and a Monet.

Hôtel Biron takes us into his world, one in which he worshipped nature, life in its immediacy. As the tour of the museum progresses it is like meeting old friends, so familiar are the likes of “Nu Sans Tête Ni Mains”, one of the figures from the Burghers of Calais, “The Tempest” with the dramatic forward thrust of his head and the staring eyes, the sensuous “Danaïd”, the extraordinary “Age of Bronze”, once again, demonstrating Rodin’s eye for nature. So much so, he was accused of casting it from a live model, a Belgian soldier. “The Walking Man”, “The Three Muses” — so it goes on; the power of “Jean D’Aire”, the passion of “The Kiss”, the gentleness of “The Hand of God”.

Each room expands on his versatility by explaining the secrets of the works’ creation, the genesis of the drama and the physicality of the end products.

One example of the creative process is shown by a maquette of tiny hands on a common or garden brick, which have been transformed by an assistant into graceful marble. This was Rodin the artistic director, having the idea and working with a team in the studio.

The versatility of Rodin’s works is shown with great clarity. Take just one room. The English poet Lady Vita Sackville West is caught in 1914 in dreamy repose (shadowed by a maquette), nearby a ceramic head of Balzac (1899), ugly, forceful, wart and all, and “Iris,The Messenger of the Gods” (1895), a vibrant, explicit, leaping torso in bronze.

Further insight into the provenance of these old friends — and an example of how he found inspiration in many places and things — come with a bizarre collection of vases and bowls that he collected and into which he introduced plaster casts of female figures in poses of varying eroticism.

A reminder of the man as well as artist is suggested in a room dedicated to the works of Camille Claudel, who was Rodin’s model, lover and inspiration for 10 years. The affair with Rodin both made her and destroyed her. Rodin was not prepared to leave the woman with whom he already lived and the unrequited love affected Claudel so profoundly that she threw away much of her work and exiled herself to an asylum, where she lived for 30 years.

When it came to establishing the museum Rodin himself insisted she should be remembered. Three versions of “The Gossips”, one of her best known works, in onyx, bronze and plaster, show the depth of her talent.

The curators are most proud of a room with a selection of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture which Rodin bought in job lots from antique dealers. For years thousands of them have been kept in storage but now 123 of them are displayed on the walls around “The Walking Man”, in a way that not only demonstrates the sculptor’s admiration of classical antiquity, but more, helped his research into how to simplify bodies, and the effect time has on material.

For example, “The Walking Man” which dominates the room was intended to be a bust of St John the Baptist, but Rodin liked the way time had caused a split and cracked the clay. He added the legs and smoothed out the rough surfaces to create the powerful figure.

The studio became a fashionable place to be. The corner room where he would exhibit his work, receive models and friends, has been restored with one or two of his collection, such as a mahogany writing desk and a corner cupboard on which he placed Greek and Chinese vases. A screen, patterned with plants, provided cover for his models where they would disrobe and walk around uninhibitedly while he sketched increasingly explicit images. He admitted: “I have been thinking about women too much ... but what could be more beautiful than thinking about women.” Only a few of these works are on show.

It was here that he encouraged young talent to visit and work with him and here that he began to think of Hôtel Biron as a museum. His legacy is such that the Minister of Culture Fleur Pellerin announced that the renovation was “a moral duty”.

A financial responsibility too. Rodin insisted that the number of moulds of his works should be limited to 12 to help fund the museum and thereby preserve his legacy, and today French regulations have kept to that concept of a “limited edition” though some estimate that there are 20 “The Thinkers” in existence.

It is a legacy that the Musée has preserved beautifully — true to the sculptor’s creative impulse, his power, the glory, even the curiosities of his collections.

In 1886 British novelist Robert Louis Stevenson wrote of Rodin in “The Times of London”: “We came forth into the streets of Paris, silenced, gratified, humbled in the thoughts of our own efforts yet with a fine sense that the age was not entirely utterly decadent and that there were worthy possibilities in art — the public is weary of statues that say nothing. Well, here is a man whose statues live and speak and speak things worth uttering.”

Catherine Chevillot, the director of Musée Rodin, says, “There is nothing to say — just to enjoy, everything is obvious. What is fantastic is to see how his place is universal to everyone. This is so definitely French but at the same time the language that Rodin uses is totally universal. That’s what makes him the great artist that everyone loves today.”

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.