Alia Ali’s parents belong to places whose borders have been redrawn. Her father was born in South Yemen, and her mother is from a town in Yugoslavia that is now in Bosnia. The Yemeni-Bosnian-American artist has lived in seven countries, speaks five languages and currently lives between New Orleans and Marrakesh. She knows what it feels like to be an outsider and what it means to create an identity that encompasses different cultures. That is why she is interested in exploring the politics and poetics of notions of identity, physical and mental borders, inclusion and exclusion, and the dualities of human existence.

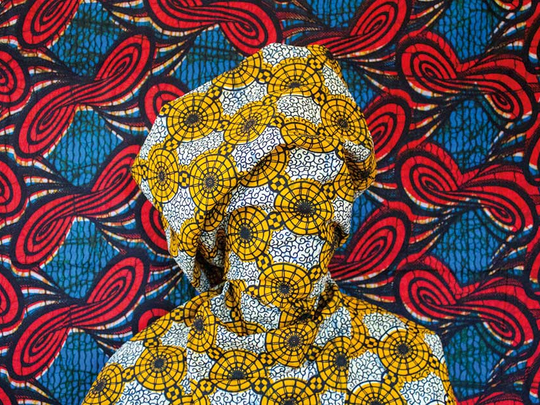

At first glance, the artworks in her latest exhibition, Borderlands, are photographs of textiles from different countries, highlighting every detail of the colours, patterns, textures and folds of the handwoven fabrics. But a closer look reveals that hidden beneath the folds in each photograph is a human figure. Each image is thus a portrait — not of a person but of a culture, representing the barriers that divide or unite people.

“The term borderland refers to the crossroads where nations and cultures collide, and interact. Borders imposed by human beings are like imprints of power and scars of violence that have an impact on the geography and the identity of those living in the porous zones around them. These borderlands are unsettled and unsettling, but also interesting to explore. I want to draw attention to these demarcated zones as transient physical spaces in the context of contemporary geo-politics,” Ali says.

The artist is known for using textiles in her work and has travelled across the globe to document traditional handwoven fabrics and the artisanal processes by which they are created. For this project, she visited 11 different regions that are known for their textiles tradition such as Oaxaca, Mexico; Bokhara, Uzbekistan; Yogyakarta, Indonesia; Sapa, Vietnam; Kyoto, Japan; Udaipur, India and Nairobi, Kenya. The unseen people in her ‘portraits’ are the craftsmen and women she met and spent time with during her travels; and she has draped the fabrics over them in ways that are typical of their culture.

“I call these people ‘–cludes’, and have left it to viewers to decide if they are ‘includes’ or ‘excludes’. These people are wrapped in layers of fabric that shield them from interacting with anything beyond the material. They are ‘undocumented’ characters, identifiable only by their symbolic connection to the fabrics which in these images are actually alienating them from the world. I want to raise questions about whether these ‘–cludes’ are hiding intentionally or being hidden; about those who have the power to decide who is included and the excludes who remain suppressed; about the fears, insecurities, misconceptions and selfish motives that dictate our notions of belonging; and about the fabricated barriers in society that prevent the incorporation of others. The idea is to make viewers think about the ways we include and exclude others in our daily lives by categorising people as good or evil, familiar or unfamiliar, threatening or safe, alien or native,” Ali says.

Alongside the artworks, the artist is displaying textiles from her collection which include Ikkat weaves from Uzbekistan, handlooms from India, colourful printed Mexican and Japanese fabrics and Indonesian batiks, and she wants to invite visitors to touch them, to observe the similarities and differences between them, and to feel the cross cultural currents they embody.

“I use textiles in my work because they are an integral part of our daily life so everyone can relate to the images and understand what they convey. Also, there are many rich cultures such as Yemen and Mexico, which have become associated with negative images. I want to tell their story through their incredible textile and craft heritage, while also creating an archive of these cultures. In my images, the fabric is personified as a carrier of history, and of personal and collective stories but it also represents the borders that separate us. However, just like the textiles we create, manmade borders are also fragile and can disintegrate over time and need to be cared for with compassion, sensitivity and a proper comprehension of what they signify,” Ali says.

Jyoti Kalsi is an arts-enthusiast based in Dubai.

Borderlands will run at Gulf Photo Plus, Alserkal Avenue, Al Quoz until April 22