One evening in 1964, Warren Beatty was making one of his regular clandestine trips to the Beverly Hills Hotel, a faux-Spanish colonial confection on a quiet stretch of Sunset Boulevard. He was meeting a paramour and wary of press attention: “I was in a state of what I felt was mandatory paranoia,” is how he recalls it. So, on spotting two men in suits loitering close to his suite, he slipped downstairs to raise the alarm. “I was told in confidence that these people were not with the tabloids, but Mr Hughes,” he says. “And I said, ‘I’m in the next suite to Howard Hughes?’ And they said, ‘We don’t know. He’s hired eight of them, and five of the bungalows’.”

By then, Hughes had been haunting the hotel for 20 years. At no little expense, the reclusive 59-year-old aviation tycoon and former owner of RKO Pictures kept a handful of suites booked in his name at all times — so that no one could ever be quite sure if he was there or not. The arrangement also accommodated whoever Hughes happened to bring with him: his then-wife, the actress Jean Peters, his assistants and security detail, and the various aspiring starlets who were said to glide through his bedchamber at night, like sushi on a conveyor belt.

Not only did the set-up put Beatty’s own romantic manoeuvrings in the shade, the then-27-year-old star was struck by the way the mogul’s fortune and obsessions had trapped him in a door-slamming farce of his own devising. As Beatty strolled back to his suite, an idea threw down roots. “I just kept thinking, ‘What a good set-up for a comedy’.”

Spool forward a little over half a century and Beatty, now 80, is in another hotel suite, this time in Claridge’s in London. He’s here to talk about that comedy: called Rules Don’t Apply, it arrived in British cinemas recently, 53 years after he first thought of it.

Beatty wrote, produced and directed the film, as well as playing Hughes, and while it’s the romantic farce he’d initially imagined, it’s also something less easily definable — an elegy for a bygone world of moviemaking that often itself felt movie-made. He greets me with a stiff salute and a just-kidding smile, and is unmistakably the same man whose “tousled charm, innocently puckered brow [and] tentatively parted lips” were swooned over by the critic Kenneth Tynan in a 1975 diary entry.

More tousled, puckered and tentative now, perhaps — but still very much a presence to be reckoned with. Beatty has been off our screens for so long that an entire generation knows him best as the quizzically smiling senior who almost-but-didn’t-quite announce this year’s Academy Award for Best Picture. (On which, more later.)

Before that, he was last seen in 2001 in Town and Country, a romantic comedy only remembered today as a significant box office wreck. The last proper Warren Beatty film — that is, one he directed, produced, starred in and co-wrote — was the madcap political satire Bulworth, way back in 1998.

His absence from the spotlight has been as sustained and absolute as was his one-time command of it. It was Bonnie and Clyde, which he starred in and produced, that in 1967 snuffed out the reign of the studios in a barrage of blood, sex and bullets. After that, Beatty became a kind of one-man studio system — a director, producer, writer and marquee-name star, who just all happened to be the same person. He’s alone in having twice been nominated for Best Actor, Best Director and Best Screenplay Oscars for a Best Picture-nominated film: a feat Orson Welles only managed once and Woody Allen once to date. (It happened in 1979, for his Capra-esque comic fantasy Heaven Can Wait, and in 1982, for his radical political epic Reds.) This, it transpires, is why he’s reluctant to sound off about the envelope mix-up in February that led to La La Land being crowned Best Picture for all of 150 seconds — before the award was passed over to the actual winner, Moonlight.

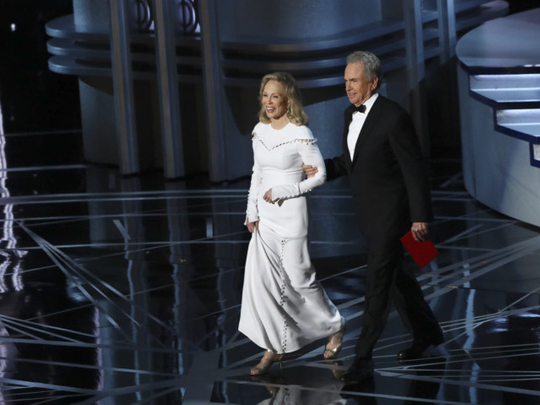

Beatty knew something was up so held back, then looked to his co-presenter and Bonnie and Clyde co-star Faye Dunaway for her view. But she misunderstood and, like a consummate Hollywood pro, smiled and read out what she’d been given. “There is something comical about it,” he winces. “But the academy has always been very kind to me, so I don’t want to pontificate about it. You know, they’ve always supported... Yeah, you’re probably aware of my...” He stops, sensing trouble. “Well, you say it.” Silence. “Your own illustrious filmmaking career?” I venture.

“Oh, yes!” he says sunnily.

Now I know how Faye Dunaway felt. Beatty’s close encounter with Hughes came three years after his big break in Elia Kazan’s Splendour in the Grass — and three years before Bonnie and Clyde made this self-described “pretty boy” and virtuoso networker a Hollywood player in his own right. He signed a contract to make his Howard Hughes film at Warner Bros in the mid-Seventies, but another decade passed before he broke ground on the script with his then-writing partner Bo Goldman — and two more until he felt ready to cast it. “I couldn’t avoid it any longer,” he says — as if the film is a professional final reckoning. For his part, Goldman had always seen Rules Don’t Apply as less of a straight Hughes biopic — in the style of, say, Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator — than a not-so-thinly veiled film a clef.

“Warren Beatty is Howard Hughes,” Goldman said in 2010. “He felt Hughes was the guy who mastered the three Fs — ‘the filmmaking, the flying and the [expletive]’, as Warren called it.” Beatty artfully demurs: “I wouldn’t say I identified with Howard Hughes, but I’m not so sure at that point Howard Hughes identified with Howard Hughes.”

He’d rather claim common ground with the film’s young lovers, chauffeur Frank Forbes (Alden Ehrenreich) and Marla Mabrey (Lily Collins), a small-town beauty queen and aspiring actress on the Hughes payroll. Both arrive in Los Angeles in 1958, one year after Beatty did — and Marla was raised a southern Baptist in Virginia, as was Beatty, along with his elder sister, the actress Shirley MacLaine. “And then, ahh, I came to Hollywood,” he laughs. He thought back then, and still does, that American attitudes to sex “make us the laughing stock of Europe. When I was a teenager, you’d go and see an Italian or French movie and it was ‘Oh my goodness, they’re nude!’”

With Bonnie and Clyde he attempted to bring a new frankness to American cinema — and a new kind of romantic lead for a forthright new age, though his own love life often spun as compelling a fantasy as anything the movies could dream up. Fact and fiction became tangled up. He and Julie Christie were lovers in Shampoo, Heaven Can Wait, Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs Miller — and also, between 1968 and 1973, in real life. For some reason this kept happening to Beatty: other notable co-stars who became romantic partners included Natalie Wood, Vivien Leigh, Goldie Hawn, Diane Keaton, Isabelle Adjani and Madonna. (To say nothing of singers, models and others.) Then came Annette Bening, whom Beatty met on the set of Bugsy in 1991.

Same old Warren, people thought — then they married the following year. (She was 33, he 54.) The couple celebrated their 25th anniversary in March, and have four children in their teens and early 20s. “Four small Eastern European countries,” is how he describes them: “I’m always negotiating.”

Settling down “had been on my mind from a very early age,” he says, “though I waited a long time to do it.”

Why?

Smiling: “I would say that I wasn’t so much afraid of marriage as afraid of divorce.” Then, deeply serious: “I just got very lucky when I met Annette. What else can I say?”

Beatty’s domestication came at just the right moment, coinciding with a rough run at the box office. When the losses from Michael Cimino’s epic western Heaven’s Gate sunk United Artists, Hollywood tightened its budgets and reined in its egos: bad news for Beatty, whose methodical pace and proclivity for tinkering were the stuff of legend, or nightmares. The 1987 Elaine May comedy Ishtar, which Beatty co-starred in and produced, was all but killed off by toxic press when its budget spiralled to a then-unthinkable $51 million. (It was nicknamed “Warren’s Gate” — and, like Cimino’s film, didn’t remotely merit the spite.) Then came Beatty’s adaptation of the noirish comic-strip Dick Tracy (1990): a mild commercial success for Disney, though apparently no money could make up for the demands it put on the studio’s time, resources and sanity.

In a 28-page internal memo that was subsequently leaked, Disney’s then-head of production Jeffrey Katzenberg advised colleagues that the next time Beatty pitched them something, they should, in his words, “allow ourselves to get very excited over what will likely be a spectacular film event, then slap ourselves a few times, throw cold water on our faces and soberly conclude that it’s not a project we should choose to get involved in”.

That’s why Beatty was unflustered by the tepid commercial reception for Rules Don’t Apply in the United States last year, where it made back just $3.6 million of its $25 million budget. “Here’s what I really think about movies,” he says. “We don’t ever know what we’ve done with one for 15 or 20 years. All I can tell you now is that Rules Don’t Apply is exactly the movie I wanted to make. So were Bonnie and Clyde, Shampoo, Bugsy and Bulworth.”

That last one is an intriguing case in point. By the late Nineties, Beatty had grown exasperated by the dominance of “big money” in American politics, so dreamt up a character — a kind of holy fool of Capitol Hill, who rediscovers his conscience during a mental breakdown — who could say everything that a real candidate couldn’t. By some accounts — though not Beatty’s — it was only directing, producing, co-writing and starring in Bulworth that prevented him from running for president himself. He

remembers taking Reds to the White House in 1981, and Ronald Reagan (an old friend, despite their political differences) telling him at the intermission: “You have to realise that nowadays there’s no business but showbusiness.”

Beatty recalls: “He said he didn’t believe anyone could be president today without being an actor.” It’s advice that clearly stayed with him. But when his name was mentioned as a potential Democratic candidate in the New Hampshire primaries before the 2000 presidential election, he didn’t pounce.

“I was flattered that people were kicking my name around,” he says. “But at the time I felt that running in a presidential primary would be a little like running for crucifixion.” Even so — and without campaigning — in the late Nineties he was polling between 10 and 12 per cent of the Democratic vote. Would his playboy past have been an issue? The example of America’s current Commander-in-Chief suggests not, though there’s a plaintive line in Bulworth in which the senator’s aide (Oliver Platt) laments: “If he just chased not quite so much [expletive], he could have gone all the way.”

Not that Beatty buys into that particular legend. A recent hair-curler of a biography by Peter Biskind suggested his conquests over the years numbered an eerily specific 12,775 — a total he dismisses as “what one can only call baloney”. “I’ve had something like 16 books written about me,” he says. “And the amount of what I would call invented memory or just stories that are concocted is quite amazing.”

Hold on a minute, though: aren’t Biskind’s book on Beatty and Beatty’s film about Hughes two sides of the same myth-making coin? Rules Don’t Apply even opens with a title-card quote attributed to Hughes — “Never check an interesting fact” - that could apply to any number of Beatty stories. “Well, Napoleon said that history is a set of lies agreed upon,” he concedes. Does he feel he lost control of his own image? “I don’t know that any of us can control our own image. We are what other people see.” He pauses. “Give me the name of that Scotsman who said ‘O wad some Power the giftie gie us, to see oursels as ithers see us!’

“Robert Burns, I say. “That’s it,” he says. “Nice thought.”

–The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2017