Obsession. Oxford English Dictionary definition; an idea or thought that continually preoccupies or intrudes on a person’s mind.

The Barbican Art Gallery in London has assembled a fabulous gallimaufry of an exhibition to illustrate just what has intruded on the minds of 14 artists in “Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector”. It opens the door into a junk shop of seemingly random knick knacks; rows of cookie jars, skulls, African masks, a 2-metre cobra and nostalgic sepia photographs. And elephants.

Take British pop artist Peter Blake. He became obsessed with collecting elephants during the 1960s when he was “over-collecting and collecting slightly madly”. He attempted to “put a safety valve on myself” by visiting the junk shops of London’s Portobello Road and buying a miniature elephant instead of “something crazy”. It satisfied his lust to buy that day but it did mean he collected every miniature elephant he saw.

Now his herd of elephants made of wood, bronze, tin and plastic, some with stripes, some green, blue or red, crowd on to the shelves of the exhibition.

The show, which is on until May 25, will appeal to anyone who has ever collected anything — Barbie dolls, stamps, coins, football brochures — and intrigue those who are searching for clues as to what makes an artist tick. To help them in that search, examples of the artists’ work are placed alongside their collection.

As the show’s curator, Lydia Yee, explains: “Some of the artists have collected for their own pleasure and some for inspiration. Some of the influences are subtle, some obvious. We have been given an intimate access to the lives and the psychology of artists and share in their wonder and appreciation of life .

“What they have in common is that they are endlessly curious. Many started collecting when young, as most children do — after all it is one of the most creative periods of our lives when we are able to construct things out of the objects that surround us and make our own worlds — but artists often take their obsession into adulthood. What distinguishes them from normal people, the private collector or a museum is that they can take their collections and make something out them.”

The result is a glorious mix of nostalgia, eccentricity, kitsch and downright weirdness but what unites them, whether it is the whimsy of Peter Blake, the deathly fascinations of Damien Hirst or the grotesque thrift shop art of Jim Shaw is their constant preoccupation with stuff, the bits and pieces of other people’s lives and, occasionally,works of a genuinely refined nature.

As Blake in an interview with curator Yee explains: “My grandmother was a mad, sort of crazy collector. She collected aluminium meat-mincing machines, which have a little handle on and you turn it. She probably had ten of those, and she never minced meat. And she collected cocktail cabinets. So in (her) tiny little house she stored four or five really elaborate cocktail cabinets.

“Very, very elaborate. And again, she never drank cocktails.”

Blake, whose 1965 collage “Kamikaze” illustrates the connection he makes between artefacts and art, bought his first pieces at a local junkyard when he was a 13-year-old art student and became the proud owner of a papier-mâché Victorian tea tray, an outsider art painting of the Queen Mary and a complete set of leather-bound Shakespeare.

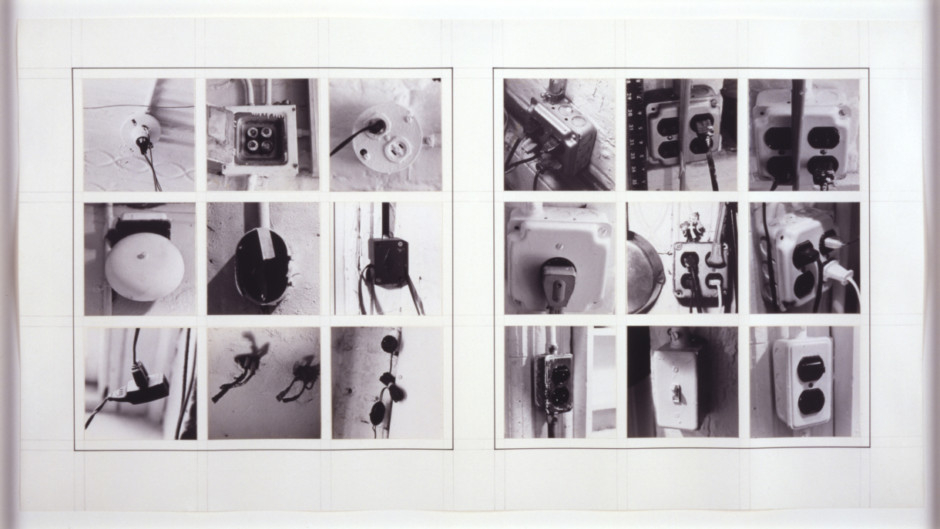

Just as it is possible to look at Blake’s collection and see how it influences — or maybe reflects — his style, the array of old sepia photographs and nostalgic picture postcards could only have been brought together by photographer Martin Parr.

He has accumulated black and white photos from the beginning of the last century of car crashes, hailstones shown beside eggs to prove how big they were, photomontages that recorded contemporary catastrophes with dramatic headlines superimposed on the accident scene. The adverts for such as Sau-Sea Shrimp cocktail, stylised scenes of holidaymakers having fun in the holiday resorts of the 1950s — Just my Cup of Tea, Bognor Regis -— and fabulously dull pictures of Britain’s early motorway service stations, capture the ordinary and allows the passing of time to imbue them with interest — not unlike his own image from 2005, entitled “Venice, Italy”, which snaps a tourist, camera to eye, bombarded by pigeons.

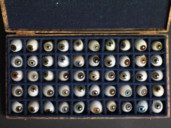

There’s an equally obvious connection between the objects and the art with Damien Hirst’s “Murderme” collection. Alongside “Last Kingdom”, (2102) his glittering glass and steel frame of butterflies, spiders and glossy beetles, is a freakish stuffed lamb with seven legs and two bodies which was actually born in a farm in Wales in 1912, a stuffed lion, 19th century anatomical models including a gruesome procedure involving pliers to remove nasal polyps and of course, rows of skulls.

Hirst, who is opening a museum in Vauxhall, south London, this year to house his collection, writes: “I think of a collection as being like a map of a person’s life, like the flotsam and jetsam washed up on the beach of somebody’s existence. A collection is deeply personal, and says so much about who the collector is, and what they believe in or are afraid of, but I think it also inevitably ends up speaking of many fundamental and universal truths.”

Similarly the shelves of cookie jars in the form of a sleeping elephant or a panda, an old Dutch woman or Red Riding Hood, could only belong to Andy Warhol. They share the same distinctive, now iconic, pop imagery of the Brillo Soap Pads Box from 1964, that accompany the display but as Steven M.L. Aronson, writer and friend of the artist observed of his mania for collecting he turned his homes into: “Clutter City. He’d saved everything, every piece of junk mail, every empty box and tin can.”

When Warhol died there were 10,000 lots put on sale in an auction that lasted ten days.

Warhol did not keep his collection in tidy rows like the cookie jars at the Barbican, instead he crammed them into every available space and, invariably, kept them tucked away behind closed doors where no stranger and few friends could stray.

Aronson describes the scene in his home-cum-artists’ factory on New York’s East 33rd Street: “He would hardly be able to open the door to the ground-floor room he called his office. Inside, desk and chairs were piled perilously high, a jacket Stephen Sprouse had given him, a scarf from Halston (both fashion designers in the 1970s and 1980s), perfume, samples from “Interview” advertisers, a painting of himself by a fan, a dessert plate pilfered from the Ritz in Madrid, walking sticks from London, a hundred pairs of sunglasses bought en masse at some nondescript flea market, and all his innumerable little teas and chocolates. The phone would ring, from somewhere under the rubble, and Andy wouldn’t be able to get at it. A world-class mess was in his successive Factories.”

In Aronson’s view Warhol was not the kind of collector obsessed with filling in gaps and making complete collections. He writes: “On the contrary — while not undiscriminating, he was essentially nondiscriminatory: interested in anything and everything. Pop is, after all, an equaliser — a Brillo box has the same value as, say, a totem pole.”

American Pae White also keeps her inspiration tucked away. Stowed away in crates she has 3,500 bed sheets, towels, dresses and tablecloths created by US designer Vera Neumann (1907–1993), whose designs were seen on Marilyn Monroe and Grace Kelly and took inspiration from artists such as Kenneth Noland, Frank Stella and Robert Mangold.

The textiles have been liberated from their crates and hang from the ceiling in a floaty splash of colours but they don’t appear to have much in common with “Cloud Clusters” (2005), tangles of coloured wire which form a delicate network of asymmetric cubic shapes which hang from the gallery ceiling.

She explains. “Every one of these scarves, tea towels, whatever, opened my eyes to a world of colour and adventure. Everyone tells a story, however mundane — where Vera went, what she saw, what amused her — and they all have designs which are clever and different.”

One of the biggest surprises is the collection belonging to Hanne Darboven (1941–2009). Much of the German’s work is minimal, to say the least, with rows of ascending and descending numbers, U-shapes, grids, line-notations and boxes reduced to U-shaped undulating lines in identical frames.

But what have we here? Of all the collections in the exhibition this is the most extravagant — a far remove from the calm, apparent order and subtlety of her art.

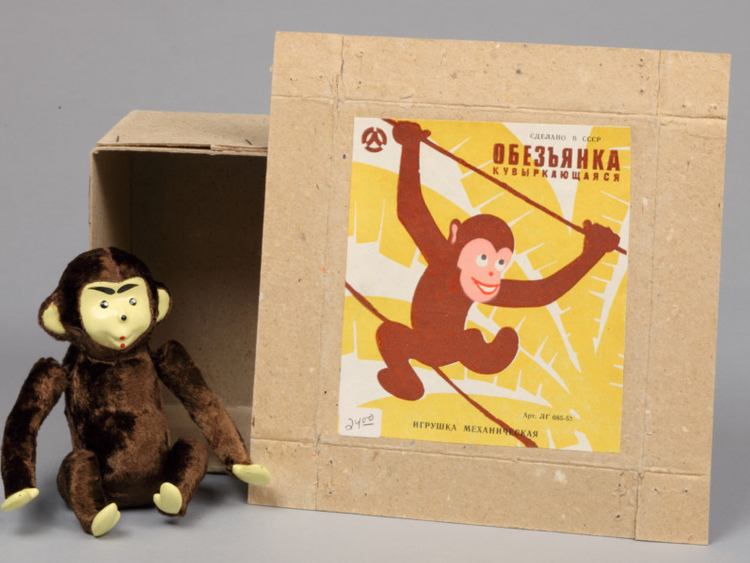

Almost all the rooms of the building complex that makes up Darboven’s family’s home in the countryside of Hamburg-Harburg, were filled with enough stuff to supply the biggest car boot sale; a Charlie Chaplin cut-out, a bronze goat, a life-sized horse, a toilet with bright blue plastic seat, an angel flying alongside a model of a World War One biplane, a huge plastic cobra and a tremendous clutter of everyday objects such as tea cups, candle holders and watches.

But as sculptor Jörg Plickart explains: “She used the collection to inspire a specific change in direction. She integrated the artefacts with her work and you can see that in the photographs displayed here from Mitarbeierter and Freunder which capture a party at her home with her friends and family and in her show “Children of this World” (1990-1996) in which she integrated 4,000 drawings, 200 dogs and 24 crazy dolls. This was another level of her work but it was still part of the same concept.”

There is no such integration with Howard Hodgkin, whose own paintings with their dramatic splashes of colour owe little to the brilliantly decorated, precise, figurative works of Indian artists in the 16th to 18th centuries which are his passion.

Hodgkin is adamant that the paintings and his own work are unrelated — as can be seen from his own “In the Studio of Jamini Roy” (1976–79) which was painted after a visit to the studio of the Bengali artist.

He was first introduced to Indian painting as a schoolboy by his art master, and was immediately attracted by its straightforwardness and “the frankness of it”. He suggests that the elephant is to Indian painting what the nude is to Western art: a central motif through which the evolution of art can be read. A gorgeous example by an unknown artist from the late 17th century, “Rao Bhao Singh Riding an Elephant”, Rajasthani, in gouache with gold and silver on paper, makes his point.

He recalls his early collecting days: “ I bought one bad picture and then another bad picture. Gradually I accumulated a lot of bad pictures. When I had accumulated quite a few, I began to realise that a collection was not just a lot of things, not one damn thing after another, like a collection of stamps or cigarette cards. It was something else. I didn’t know quite what, but that was the first stirring that maybe there was more to it than this.”

Unlike some of the others who accumulate one thing after another out of curiosity or in the hope of inspiration, Hodgkin seems to have been on a long quest for perfection.

“What I’m trying to convey is that collecting is very, very hard work. And strangely unrewarding, because if one has to — as several times in my life I have had to — break off a certain section of one’s collection as if it were a piece of peanut brittle and exchange it for one, perhaps quite small picture, it doesn’t necessarily make you like the new picture very much. You have to get used to it. In the end, you really have to forgive it, before you forgive yourself.

“That takes me to the next thing, which is the awful autonomy of the collection. It’s like Frankenstein’s monster. It’s like having something that you can’t ever lock up in the cupboard, because it’s always coming out again.”

The obsessive nature of the collector is common to all, whether they are drawn to the quirky or the kitsch, the vernacular or the finely crafted. Japanese-born Hiroshi Sugimoto, who recreates historical scenes in wax such as “Benjamin Franklin” (1999), opened a gallery in New York specialising in Japanese art and Martin Wong (1946-1999) accumulated an uproarious array of plastic hamburgers Disney characters, little Chinese Buddhas and porcelain princesses.

Dr Lakra, a Mexican tattoo artist, visited flea markets to fill his studio with images from discarded scrapbooks and record covers while Sol Lewitt often swapped his artworks with friends such as Hanne Darboven and became interested in Japanese woodblock prints. Edmund de Waal whose cool, poised, works such as “From The Collection of a Private Man” (2011) reflect his collection of netsuke, tiny hand carved objects left to him by a great uncle and immortalised in his book “The Hare with the Amber Eyes”.

The French artist Arman (1928-2005), who was fascinated by tools, clocks, jewellery or oddities such as Second World War gas masks which he framed in a wooden box to create “Home Sweet Home”, (1960) was bewitched by African masks.

For sheer oddness, few compete with the thrift store paintings of American surrealist Jim Shaw. He rummaged around the charity stores and garage sales of his native Michigan when he was a young man in the 1960s and 1970s and developed a fascination for paintings that were badly executed, cheap and invariably grotesque.

Who would want a painting of a pink mountain lion, a smiling cat, or a man with a fox nestling on his head? Well, Shaw does — he relishes their very oddness, their sheer unlike-ability and, above all, their weirdness.

As far as he was concerned, the weirder the better. He explains: “And that’s why there’s so many surrealist paintings in there. There aren’t that many abstractions, because it’s quite hard to find an abstraction that’s interesting but, you know, amateur. I’ve found some, but they’re not loaded with the same psychosexual subtext that a painting of a little kid is, or a broken heart over a Dalíesque landscape.

He found collecting was “always a sort of archaeological or paleontological dig”, which prompts curator Lee to ask him: “So in some ways you’re like an anthropologist digging up the layers of this history?”

He replied: “That’s the way I like to romanticise it. I’m just a nerd, is what I really am. A manic nerd. But I am old enough to know that I don’t need to keep collecting stuff.”

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.

The exhibition will run at the Barbican Art Gallery in London until May 25.