Rio de Janeiro is in ferment. Work to ensure that the Olympic Games open on time and in shape on August 5 have turned parts of the Brazilian city into building sites. Tram routes which are planned to ferry athletics fans to their venues have created a morass of closed streets and traffic jams. All this for $13.2 billion (Dh48.5 billion) — and rising — which many argue should have been spent on the city’s chronic slums, the infamous favelas.

The country too, is in chaos with high unemployment, high inflation and a government scandal that saw the suspension of Dilma Rousseff as president. She now faces an impeachment trial.

So, far from enthusing the art market the Olympics seems to be having the opposite effect. No wonder Juliana Cintra, co-owner of the art gallery Silvia Cintra + Box 4 in the wealthy Rio suburb of Gavea, is looking ahead with some pessimism despite a recent assessment by Sotheby’s that the Brazilian market has grown faster than most in the last five years.

“We have decided not to go to any an international art fairs this year apart from Basel Miami and Brussels,” she says. “We were invited by Dubai but we have to take a step back because of the Brazilian real has weakened considerably against the dollar since last year. We have a political crisis with corruption in the government and we worry about the situation in Paris and Brussels due to terrorism. People are not in the mood to buy art because it is something you buy when you are happy. It isn’t something that you need.”

This is not to say that the arts scene in Rio is moribund. The city is home to many of the country’s best known artists such as Daniel Senise, Ernesto Neto and Adriana Varejão, who recently opened in the Lehmann Maupin gallery, New York, with a collection of portraits. Perhaps one of the most high-profile is Vik Muniz, who creates startling images out of apparently random bits and pieces such as tomato sauce, chocolate, sand and rubbish. Despite settling in New York in 1983, he has a home in Rio and is involved in building a school of technology for deprived children.

The institutions seem also to be playing their part in reflecting talent. The Museum of Modern Art stages a steady flow of exhibitions — four or five artists on show at a time — including, for example, design, architecture and recently, a retrospective of the Opinião 65 group whose art sprang out of opposition to the dictatorship in Brazil from 1964 to 1985. Their realistic style had a huge influence on succeeding generations.

The Museum of Rio Art was opened in 2013 in the lead up to the 2014 football World Cup. With three contrasting buildings under a single wave of a roof, it has a permanent collection of 18th-century art alongside shows involving contemporary artists.

The Paço Imperial, or Imperial Palace, used as a royal residence in the early 19th century, has turned its sensitively restored rooms into galleries and is staging an exhibition of contemporary art to coincide with the Games while across the bay, the swirling curves of architect Oscar Niemeyer’s Niterói Contemporary Art Museum houses a mix of exhibitions and events.

ArtRio, the annual art fair, which will be held in September, hopes to build on the success of the fifth edition last September, which had 52,000 visitors and 80 galleries, including London’s White Cube, and is beginning to match São Paulo’s hold on the commercial art market whose annual fair SP-Arte attracted more than 140 galleries and 23,000 visitors in April 2015.

Not yet in the same league as São Paulo for private galleries, Rio is championing the quest for young talent.

“About 12 years ago we started a summer show with the aim of bringing in the young,” says Juliana Cintra, whose mother Silvia opened the original gallery 35 years ago. “We needed more space so I opened + Box 4 which is more like an experimental space. At that time in Rio a lot of young people were emerging. It was a great moment.”

The walls of what is indeed a square white box are lined with works by artists — most of whom might not be well known outside Brazil — such as Miguel Rio Branco, a Magnum photographer, the sculptor Amilcar de Castro and painter Cristina Canale. Carlito Carvalhosa who was the first Brazilian to be given a show at MoMA, New York.

“Our project is to put together artists for different genres and create some kind of balance,” says Juliana.

Is there a style specific to Rio? Are artists involved in espousing a political message as they were with Opinião 65? She says not. “It is hard even to say that this or that artist is from Brazil. Art is now global. Everyone wants an international career, many study abroad and have galleries overseas.”

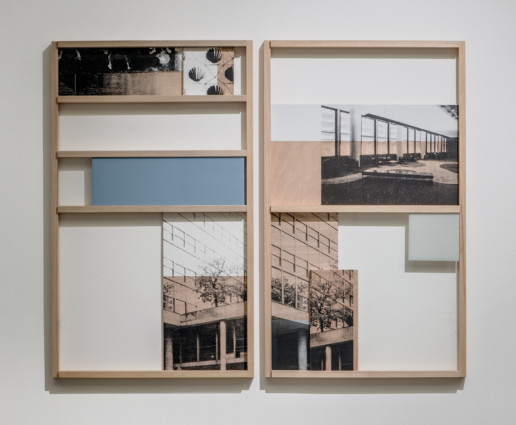

Laercio Redondo, who is associated with the Cintra gallery, studied in Stockholm but is spending an increasing amount of time in Rio where he has a tiny studio two blocks from Copacabana beach. Some of his work, if not stridently political, certainly reflects on Brazil’s exploitation by its Portuguese masters during colonial rule and on slavery which was not abolished until 1888.

“My work deals with memory,” he says. “I talk about collective forgetting. How do we build history, what kind of history do we tell? I try to find small fragments about people that are not here with us today but are still relevant to talk about. We talk so much about the future but we should think about the present — and to do that we need to understand the past.”

His work is hard to categorise; some installation, some video and paintings. Take one example inspired by one Jean-Baptiste Debret, court painter to the royal court in Rio for about 15 years from 1816. He painted hundreds of scenes of street life — the fruit sellers, the musicians, the indigenous people and the slaves.

“The only document we have to understand class and labour of those days is through his paintings,” says Redondo who has taken images by the French artist and re-imagined them in “Sale — Faulty Memory Game”. He contrasts the 19th-century scenes with present day images, each printed on opposite sides of plywood panels. The viewer has to pick up the panels and turn them round to compare the original with Redondo’s interpretation. They depict the same scenes, but differently — the inference being that issues such as slavery, the slums, or the hardship of scraping a living are as difficult today as they were 200 years ago.

“I don’t think my work is just about Brazil,” says Redondo. He will have a solo show at Dallas Contemporary Texas this September. “I think these are the problems that are the same everywhere. I am just working from my small canvas out to the world. I think it has a lot say.”

Does he detect any kind of movement such as the Opinião 65? Anything like the YBAs, the Young British Artists, who dominated art in that country in the 1990s?

“That was much more a creation of the market than them actually being some kind of movement,” he says. “I don’t really think it’s the same here but we do have lots of collectives in Rio and I do see a resistance by people to the present situation — brilliant young people trying to do something, discussing things and taking part in manifestations as they did before the World Cup. (When there were huge protest marches against the cost of the enterprise). “Rio is an amazing city but we have to consider that it is hard to be positive at the moment. Things are very tense over the Olympics. People not happy and there is a resistance to issues of race and gender, and unfairness. There is a generation trying to say something here.”

Some of that generation can be discovered on a side street deep in the Centro district of the city. Here in two buildings, Number 11 and Number 17 Gonçalves Ledo Street, is A Gentil Carioca, a gallery as apparently informal and indifferent to image as the scruffy buildings it inhabits. By day the area is a cacophony of shops and market stalls — a far cry from Silvia Cintra + Box 4 in sophisticated Gavea — but both share aims which are not that different.

The gallery was founded in 2003 by three of Rio’s most influential artists — Marcio Botner, Laura Lima and Neto, best known for his interactive pieces and who was at the Venice Biennale in 2001 and at London’s Hayward Gallery.

The aim, says director Elsa Ravazzolo Botner, was to fill a gap left by the public institutions in the city and to give young artists a space to show their work. It began with what sounds like cheerful amateurism.

Elsa Botner recalls how, in the early days, Neto was asked for an invoice. “He said, ‘What is an invoice? I shall have to phone my gallery in New York to find out’.” And when Marcio had to leave the gallery for a while, he would put up a sign saying “back soon”.

“It was like a project room where people came and just did things. In the first year the gallery staged exhibitions which lasted for maybe as short as one day, one week or one month.”

The gallery is a little more professional these days. It went to its first international fair, Basel Miami, in 2005, with a show entitled “Nada” (Nothing) which suitably reflected its anarchist leanings.

Since then, the gallery has represented artists that it has discovered at Art Basel, Fiac in Paris, Artissima, Turin, abc Berlin and ARCO Madrid.

“The founders asked: ‘What are we doing with the fantastic material we are discovering? We need to make a show for them.’ So we started one which is only for young artists without gallery representation and who have not exhibited before,” Elsa Botner says.

Called “Abre Alas” (roughly: opens the way), which refers to the float that heads the parade of the Samba schools in carnival, the entrants are chosen by three curators — they are different each year. This April they picked 20 artists out of 550 hopefuls.

The curators explained their choice of contributors. “One of the most pleasurable things when working with art is to find new artists. It’s great when we came across a work that really touches us. Inspired by this feeling that we present the 12th “Abre Alas” with exciting artists working with an experimental bias and searching for their own voices. Artists who work in a charming, serious and consistent manner.”

The youthful talent did not disappoint for riotous self-expression, whether it involved skateboarding over blue and black geometric painted shapes (Renato Custodio) or the work of the Indigestion Group who filled sausages while discussing “art and its intricacies”. The discussion was followed by a tasting.

In an attempt to foster a community spirit in the district the blank wall outside Number 17 is given over to a project by an artist sponsored by a collector who expects nothing in return and often has no idea what the work will be.

“Art can make changes,” says Marcio Botner. “We use the wall as a place for anything, from huge hula hoops as it is now to showers that anyone could use. People stop on their way from market and ask: Why is that there? What function is it serving? They become infused with the art, they talk about it, it’s educational. It is like a cultural bomb.”

Like many in the artistic community — like many in Rio — the gallery shares the worries about the economy, the unhelpful rate of the dollar and the corruption, but, undeterred, this year it is showing at Frieze, New York and London.

No doubt they now know what an invoice is.

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.