When Indian art collector Kiran Nadar ran out of wall space in her house to hang paintings she did not do what many would have considered sensible: stop. Instead she kept going, buying art work after art work. What was an urge to fill her home with colour became a passion.

But where to hang these treasures?

The answer: she founded her own museum. The Kiran Nadar Museum of Art opened its doors to the public in January 2010, exhibiting modern and contemporary works from India and the subcontinent.

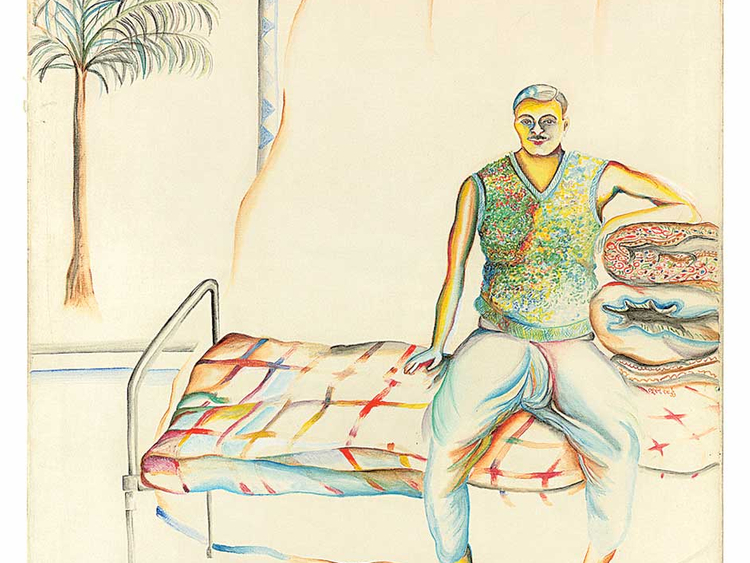

Untitled (Portrait of Pandoo) by Bhupen Khakhar, 1977

“I felt I could not keep works in storage where they could not be seen,” she says. “I thought I should do something meaningful with them. Now, not only can I share my passion with other people, I get to see them myself all the time.”

The museum is on two sites in Delhi, India, and has an unrivalled collection of more than 3,000 works by artists who are familiar in India, but perhaps less so elsewhere, though her contribution of works to a show by Indian artist Bhupen Khakhar (1934-2003) at Tate Modern, London, “You Can’t Please All”, (until November 6) will have raised the profile.

Her early inspiration came from the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group, a short-lived cluster of like minds founded in 1947 to challenge India’s existing conservative art establishment. Founder members included M.F. Husain, S.K. Bakre, Krishen Khanna and V.S. Gaitonde whose “Blue Abstract”, oil on canvas, is one of her favourites in the museum.

“When I started to share my collection with a wider public, my approach to collecting changed,” says Nadar, who is married to Shiv Nadar, the founder of the IT services giant HCL Technologies. “I became more oriented to treating it like an institution than a home and acquired huge works such as Subodh Gupta’s ‘Line of Control’ which obviously needs a lot of space to display.”

It certainly does. The work is a mushroom cloud — the kind the world witnessed when Hiroshima was bombed — made with shiny kitchen utensils, and weighing 26 tonnes. It took three cranes to lift it into place and seven days to install. The installation came to international attention in 2009 when it was displayed at the Tate Modern Triennial.

Bharti Kher’s “The Skin Speaks A Language Not Its Own”, a huge life-size elephant adorned with thousands of bindis, was sold at Sotheby’s of London in 2010 for $1.5 million (Dh5.5 million), making her the top-selling female Indian artist of the time.

Nadar enthuses about the conceptual artist Tallur whose work adapts handmade craftsmanship, with industrial objects and she has several of the eerie monochromes by the veteran artist Rameshwar Broota.

The De-Luxe Tailors by Bhupen Khakhar, 1972

She is clearly hands on when it comes to acquisitions, but has curators to help her. “I do still rely a lot on my own eye, but I am learning as I go,” she says. “My knowledge of art and its history has grown with my passion for collecting.”

Her eye has helped her identify which artists are important and to discover unknown talents who have yet to receive the critical attention they deserve. “I am able to recognise where gaps arise that need to be addressed,” she says.

Above all, she is proud that the museum is not a commercial venture — nothing is for sale and entry is free. “It’s philanthropic,” she says. “It’s a nice feeling.”

She also feels it part of her mission to spread the word of Indian art at home and abroad. Quite a challenge; private art museums are a relatively new development in India and the habit of actually going to a museum is also in its infancy. She is concerned about a “disconnect between art and the public” in India, an issue which appears to her to be of little concern to the country’s government-run institutions. By developing its extensive public programme, KNMA looks to build a strong “museum-going culture”.

In Delhi itself an ambitious show dedicated solely to video works will run until December 8. Entitled “Enactments and Each Passing Day”, it is a selection of works by 15 contemporary artists of different generations, the exhibition “contests and negotiates” between opposites such as the iconic and the frivolous, Mao and Gandhi, a physicist and a miniaturist. According to the publicity for the show, it “speaks through ascents and accents, dissolutions, dislocations, territorial claims, apocalyptic signs, body and the double, and public icons”. Quite a claim! The exhibition is drawn from KNMA’s own collection with loans from other artists.

The robust works of ground-breaking abstract painter Jeram Patel, who died earlier this year, are being displayed in a show entitled “The Dark Loam: Between Memory and Membrane”, which runs until December 20.

There are plans for a new, bigger, custom-built museum to replace the existing set-up which is housed in two buildings, one in a commercial unit between numerous offices and a shopping mall. That will help the KNMA raise the profile of modern art in the subcontinent. It will also become a meeting place, a venue for student workshops and, indeed, any activity that will help bridge the gap between the public and their understanding of art — something that many people see as elitist. “People must be encouraged to discover that a museum is not a stultified, boring, moth-eaten place,” she says.

Nadar has set up a foundation to send deprived children to a top Indian private school and she is rightly proud that 200 graduated last year. The foundation collaborates with other schools and colleges, NGOs and charitable trusts, using workshops where adults and children alike learn about new art forms and techniques. Her hope is to encourage youngsters to become so engaged in art by using exercises such as drawing their own interpretation of the works they see, that they, the children, change their parents’ attitudes,

“The museum’s accessibility is what will bring it closer to people and make it a part of their lives,” she says. “We have a lot of great artists in India and it’s a shame that not enough people know about them. Apart from its educational value, creativity and aesthetic experience must remain central to human existence as contemporary life gets more hurried and stressful.”

American Survey Officer by Bhupen Khakhar, 1969

She is determined to spread the word about Indian artists abroad and readily admits that she would like to be remembered as having established something in the field of art rather in the way of the notable collectors and philanthropists such as Peggy Guggenheim or the Rockefellers.

She is supporting “Life Will Never Be The Same Again”, a solo exhibition of dense abstracts by Jayashree Chakravarty, at Musée Des Arts Asiatiques, Nice, France, (until February 15, 2017) and recently the detailed, complex drawings of Nasreen Mohamedi were shown in Madrid and New York.

She contributed three paintings to the Tate’s Bhupen Khakhar show, “American Survey Officer”, “Night” and “Republic Day”, and admires the artist for his “tremendous use of imagery and his strong use of colour and focus”.

“He was a self-trained artist and he had no commercial training,” she says. “He developed his own style ... He was a very interesting man.”

Most papers in the UK reacted enthusiastically to the show, one suggesting that Khakhar “gives us modern Indian art as the romantically inclined Westerner would like to imagine it: magic realist images of small-town life in vibrantly intense colours, painted with a quirky disregard for Western conventions of space and composition”.

Not interesting or quirky enough for the critic of the “Guardian”, who wrote that the paintings were “brightly coloured but emotionally inert ... He [Khakhar] is genuinely just not much good”. And he went on: “What makes this an odd exhibition for Tate Modern to put on is that Khakhar so strongly resembles the kind of British painter it would never let through its doors. Why are we supposed to be interested in this old-fashioned, second-rate artist whose paintings are stuck in a time warp of 1980s neo-figurative cliché?”

Members of the Indian artistic community reacted fiercely, calling the critic and the “Guardian” ignorant and neo-colonialist. But Nadar simply says: “It was a narrow-minded review but maybe that did us a favour by giving it extra publicity.”

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.