When the Greek philosopher Socrates returned from military service in 432BC, he hastened to a wrestling school where he was introduced to the Athenian Harry Styles of his day, an athlete called Charmides who was “fair of face and sound of heart” and pursued by admirers wherever he went.

Apparently, “all gazed at him as if he were a statue” and Socrates, overwhelmed by the sight of such beauty reputedly enthused that if Charmides were to remove his clothes, “he would appear to have no face so perfect is the beauty of his body”.

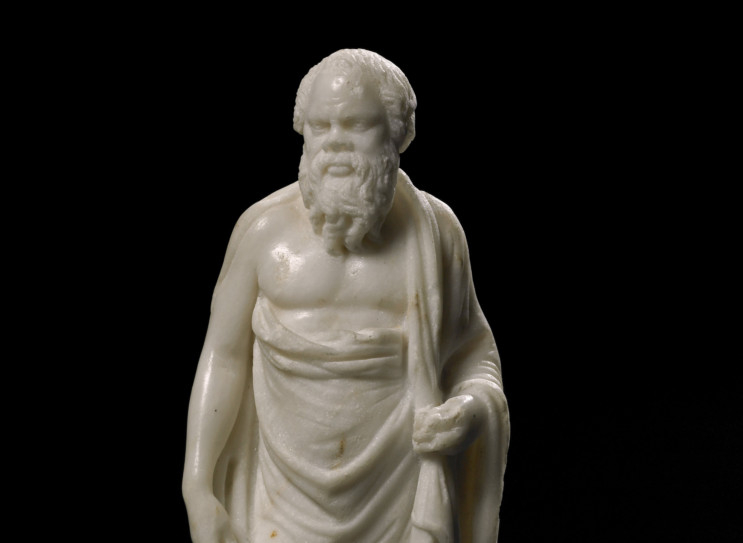

In the latest exhibition at London’s British Museum, “Defining Beauty: the Body in Greek Art”, deities are represented as men, men as deities. Few expressed the philosophy of their art better than Greek essayist Maximus of Tyre who wrote in the second century AD: “The Greek custom is to represent the [deities] by the most beautiful things on earth — pure material, human form, consummate art.”

The exhibition celebrates the Greek vision of perfection, but also traces the growth of realism, the use of paint and decoration, and the role of women. Many of the 150 exhibits are from the Museum’s own collection — including the Elgin Marbles. Illisos the river deity is back from his controversial stay in the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, and Iris, whose long-gone bronze wings were poised over the west pediment of the Parthenon (438-432BC), still exudes a lust for life beneath her clinging robes.

While Iris is carefully, if erotically, covered, the men that greet the visitor to the opening room of the exhibition are proud, upright, muscled figures, honed to perfection. And, of course, they are naked.

The spear carrier, or Doryphoros, first brought to life around 440-430BC by the master bronze worker Polykleitos of Argos (C450–420BC) may be a 20th century reconstruction but he is still the classic personification of athletic, male beauty while Diskobolos — the discus-thrower — would surely have enraptured Socrates as much as his wrestler.

Athletic and muscular, this is the work of Myron, one of ancient Greece’s most influential sculptors, who around 450–440BC cast his vigorous youth in bronze. Recreated in marble by the Romans he is poised to let fly, his left arm points down to balance the swing of the discus, his pecs are finely honed, the muscles in his left leg tautened to take the weight.

Many Greek works were destroyed by late antiquity when they were judged to be more use as scrap than art, but by the end of the first century BC when Greece was part of the Roman Empire, Romans became captivated by Greek culture and collected and commissioned copies of famous Hellenic artworks.

One survivor is Apoxyomenos from about 300BC, which was found in 1996 on the Adriatic Sea. Another wrestler, his eyes fiercely focused — perhaps on the fight to come — holds a metal scraper or strigil (now missing) to remove the oil mixed with dust that protected his skin from the sun.

Socrates again: “In portraying ideal types of beauty ... you bring together from many models the most beautiful of features of each.” The wrestler satisfies his criteria.

There is no doubt that this celebration of the naked human form — invariably male — was homo-erotic. As the 5th century BC poet Bacchylides observed about a performer at an athletic event: “He showed his body to the great ring of watching Greeks as he threw the round discus ... to the steep heights of heaven.”

But nudity was also a sign of superiority. How else to prove fitness for battle than by fighting naked, unprotected, unafraid? The Greeks saw the naked body not just as evidence of physical but of moral ascendancy. But for the Assyrians, for example, as a panel from Nimrud in northern Iraq illustrates, their defeated enemies are naked and dishonoured — the ultimate humiliation.

Seen today in the white purity of the original marble, it is hard to imagine how these Greek deities and heroes would have looked at the time, but colour was important to ancient ideas of beauty with the statues painted often in gaudy hues. The effect is that they look more natural, more human.

The reconstruction of an archer (490-480BC) displays the bright chequered colours of his tunic and leggings while a bronze of the deity Athena by Pheidias, one of the most important sculptors of his day, has been reconstructed in all her glittering gold and silver.

This did not impress Michelangelo centuries later. He revived the Greek way of representing the body but he refused to use colour — partly because it was inappropriate to copy the richly decorated saints of the Renaissance period but also because he considered to do so would be untrue to the pure aesthetic of Greek art.

With the Roman period came an increasing naturalism. The results are the sternly expressive heads of the writer Homer and the dramatist Sophocles, the delightful Laughing Boy, the comic runaway slave sat on a household altar and terracotta “grotesques” suffering from various disfigurements.

The bronze statue of a baby (between the first century BC and first century AD) is as life-like and ebullient as the fisherman selling his wares is sinewy and worn — a man who has obviously lived hard with his untidy hair and beard and coarse animal skin garments.

But what of women? In a male dominated society such as Greece, it was always men that represented their idealised world, and women — and deities — knew their place as mothers, providers of male heirs and homemakers. Men considered them to be wild and passionate, something of a threat, that had to be contained so most are clothed or if not, pose decorously with hands strategically placed, eyes fixed demurely downwards.

Demeter, the deity of nature who presided over women in this patriarchal world, symbolises the modesty and serenity of perfect Greek womanhood.

Nonetheless, Aphrodite, the deity of love, whose posterior greets the visitor to the exhibition, is an altogether more ambiguous — and beguiling — figure. While the men who share the opening gallery with her — such as the discus thrower and Apoxyomenos — are proudly naked, she is crouching as she bathes, her back towards the crowds. She is not bold like the men who meet the onlooker with a challenging gaze yet her sideways look suggests she is not one to be intimidated. Is she hiding her charms or is she being seductive? Maybe she is poised to strike those who gaze illicitly upon her? She is both divine and dangerous.

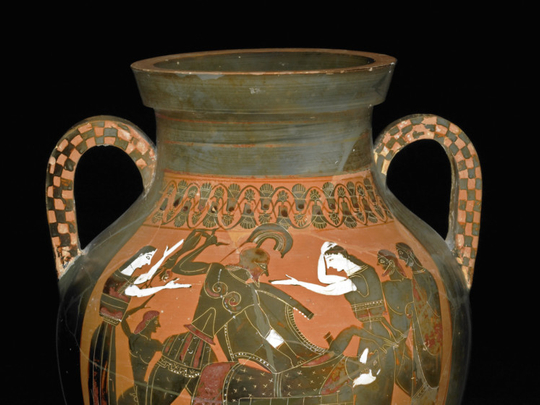

Often, women are portrayed on vases for the entertainment of (male) voyeurs in various erotic scenes such as bathing and dressing but none tease more than the languorous form of Hermaproditos, offspring of Hermes and Aphrodite who lounges seductively on a couch — a female figure from behind but something quite different from the front.

Either way, nothing matches the battered, limbless Hercules, known as the Belvedere Torso, for power and majesty.

The German playwright Friedrich Schiller was overwhelmed when he first saw it in 1785. He wrote: “This torso tells me that two thousand years ago a great person existed who was able to create such a thing — that a nation existed to give ideals to the artist who made it — that this nation believed in truth and beauty.”

Michelangelo too was in awe. He refused to restore the massive figure because, despite the destruction wrought by time, he felt it was close to perfection and could not be improved — even by him.

Richard Holledge is writer based in London.

‘Defining Beauty: The Body in Ancient Greek Art’ is on at the British Museum until July 5. Tickets available at britishmuseum.org.