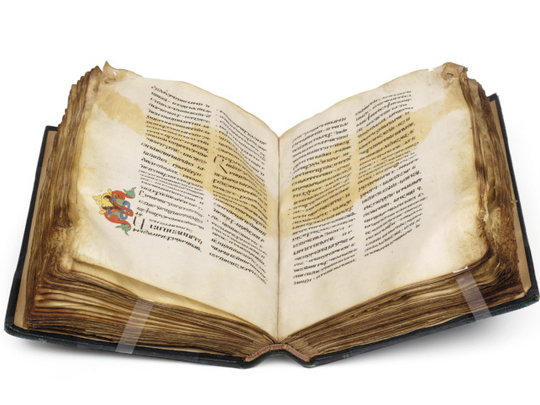

It has been well used. Its edges are scruffy and blackened, guttering candles may have spat wax over it and burnt its pages. It looks like an iron was carelessly rested on it. Written in the 11th century, it is the oldest manuscript on display in a sublime exhibition at Oxford’s Bodleian Library entitled “Armenia: Masterpieces from an Enduring Culture”.

The manuscript is a copy of a commentary on the “Epistle to the Ephesians” by John Chrysostom, the archbishop of Constantinople (now Istanbul) from 397 to 405. The Epistle was an exhortation to the people of Ephesus in what is modern-day Turkey to embrace the Christian faith and is assumed to have been written by St Paul the Apostle, who proselytised the word of Jesus Christ in about AD60.

It is a work of pure clarity and absolute discipline with every line of words straight as a die, all the spacing regular. It is as if it was set by computer rather than by a scribe following lines pricked out by pin on paper, the technique used by ancient Armenians.

The commentary is by no means as beautiful as many of the 100-plus objects on display but there is a poignancy about it; the sheer age, the sense that it has been held by thousands of the faithful and pored over, its words reverberating around a church or being read by a family at prayer.

And there is a kind of beauty in its evocation of a history which, in the case of Armenia, has been more chaotic and calamitous than many countries. The exhibition is being staged to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the setting up of the Chair in Armenian Studies at the Bodleian under the aegis of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and to commemorate the year 1915 when Armenians were dispossessed from their lands in Turkey by the rulers of the Ottoman Empire.

What the exhibition demonstrates is that despite conquest and massacre the Armenian diaspora, which spread over the centuries across the globe, has kept its language, its faith and the cultural heritage.

To fully appreciate the exhibition it is important to have a sense of Armenian history — for this is a country that has suffered since the first of its people settled in the Caucasus region of Eurasia some 3,000 years ago with territory that stretched from the Mediterranean to the Caspian Sea.

At the beginning of the 4th century AD it became the first nation in the world to make Christianity its official religion but certainty of faith was insufficient to guarantee security. Control of the region shifted from one empire to another, with the Armenians being subsumed by the Persians from about 500BC, the Romans, the Byzantines and the Ottoman empire that dominated the area from the 16th century to 1920.

A map on the walls of the Weston Library — a newly renovated space for the Bodleian — shows how Armenia, today locked between Georgia, Turkey, Azerbaijan and Iran, is one-tenth the size it once was.

What is made clear is how the culture of the country not only survived its vicissitudes but also how its writings became an expression of its identity with vibrant printing centres in many European capitals such as Venice, Rome and Constantinople.

At the heart of this identity was the invention of the alphabet by a monk, Mesrop St Mašto, in AD405. He used 36 signs to reflect sounds of the language and started a handwriting tradition, used mainly to translate scriptures, that lasted until the 19th century when printing took over. The alphabet became the symbol as the protector of Armenian culture and a source of pride and continuity as the reluctant diaspora of exiles grew.

One of the most traumatic expulsions came in 1604 when the Safavid Shah Abbas, whose Persian army had defeated the Ottomans, deported several hundred thousand Armenians from the Ararat Valley in what is today the border between Turkey and Armenia to his new capital of Isfahan in Persia.

An Armenian priest lamented how Abbas “destroyed and made desolate all houses and dwellings so that people hid in fortresses and clefts ... some he found and slaughtered, others he took captive”.

Thanks to the resilience of the exiles who built a settlement near Isfahan called New Julfa, creativity flowered out of adversity, resulting in works whose rich decoration adds not just lustre but power to the Christian message.

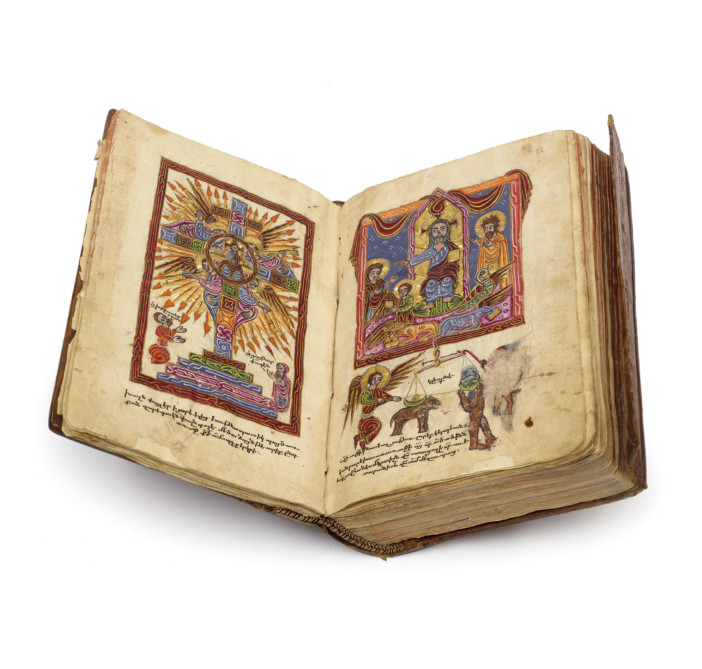

“Last Judgment” (1609) has a triumphant Christ on a cross of swirling blues, golds and greens while on the facing page Christ is on a throne overlooking the weighing of souls; an angel tugging at the scales to spare the judged from perdition while at the other end, the devil does his damnedest. At some stage the figure of the devil has been rubbed out as if to render him powerless, but a recent X-ray revealed the devil looking less than evil incarnate but a rather bored jobsworth going about his daily chores.

The sumptuous detail of the “Adoration of the Magi”, “the Revelation to the Shepherds” (1632) and the triumphant “Christ in Glory” (1631) shows a wonderful use of rich pigments of greens and gold and most valuable of all, lapis lazuli — that was found in mountain caves — for the blue. The draughtsmanship is elegant, often with the letters of the alphabet in the form of birds.

One of the most surprising works from the New Julfa era — to the Bodleian at least — is the “Psalms of David”, which was found by an Arabic scholar in Aleppo in the 17th century and bought by the university for £600 after he died in 1703. It was only in 1969 that a scholar at the library realised that the “Psalms” were published in 1638 and, more, was the first to be printed in Iran. Unlike the commentary on the “Epistle to the Ephesians” it has a lengthy colophon — a record of the scribe and the provenance of the book — which reveals the head printer’s frustration at lack of experienced scribes, the shortage of typefaces and the fact that they had to make the paper and the ink themselves. There is also an insight into internal politics; the conservative faction in the Armenian Church did not see the advantages of printing and were opposed by the copyists, who feared for their livelihoods.

Sometimes the colophons record the day-to-day life of a scribe — whether they were cold, if they were enjoying themselves — and this records how the monks who wrote the original version of the “Book of Psalms” in 1087 “for one year and five months, day and night without pause work[ed] with the brotherhood of this monastery, because we have not seen this [i.e., printing, from the example] of a master, and we have no teacher, except for the Holy Spirit alone”.

Most of the works are religious but storytelling, songs and poetry played a major part in the culture.

The frankly grotesque depiction of Alexander the Great’s horse Bucephalus (1544) made up of strange creatures illustrates a romance about the Greek leader and is one of the earliest illuminated secular works.

Some of the most intriguing books are almanacs, or DIY books for humbler folk and merchants, such as guides to the zodiac, calendars and maps and manuals for calculating currency, weights and measures as well as for the playing of musical instruments. These books were often treated as part of a communal service and lent to any family that had an ailing member or was in trouble.

Many of these were printed in Venice and Constantinople as well as Amsterdam and Rome, where techniques were more refined. One of the zodiacs, which examines the characteristics of the star signs Aries and Taurus, is a sophisticated work by a printer called Yakob. He was based in Venice, which by the early 16th century, had become the biggest Armenian community in the West. It is displayed close to the “Psalms of David” which was created more than 100 years later. Yet, tellingly, the standard of work from Venice is considerably more refined compared with the labour-intensive workmanship of the New Julfa scribes.

After centuries of shaky co-existence with their Ottoman overlords in Turkey, a new threat loomed. As the Ottoman Empire began to fall apart at the end of the 19th century, the Sultan, Abdul Hamid II, launched a vicious campaign against the Armenians. Between 1894 and 1896 villages were destroyed and hundreds of thousands were murdered. In 1908, the Sultan was overthrown, a new breed of nationalistic Young Turks took power and on the pretext that many Armenians fought with the Russians against the Turks in the First World War decided to “remove” Armenians from the war zones along the Eastern Front.

On April 24, 1915, the government expelled thousands from their homes and set up killing squads to rid the country of “Christian elements”, with the result that by 1922 there were only 388,000 Armenians remaining in the Ottoman Empire.

The loss of life and homes, the subjugation of a people and the resulting migration of refugees intensified the need to preserve the culture and any sense of national identity.

The collection as a whole is a moving testimonial to the spirit of survival over the centuries and to single out anything as a symbol of that durability might be invidious, but one book has a story of great eloquence.

It springs from a bedraggled “Book of Prayers”, printed in Constantinople in 1782, yellowed with time, ragged and coming apart, its leather binding detached. It has been lent to the exhibition by an Armenian family living in Yorkshire, England, whose forebears have owned the book — or Nareg as it is known — since 1885. The first owner was given the book when he became a priest in Diyarbakır, southeast Turkey, in 1885. He took it with him to Mosul, northern Iraq, where he served with such distinction that when he died was honoured not just by his Christian congregation but also the Muslims.

The book passed to his eldest son, a tailor, who set up an orphanage for the victims of the 1915 expulsion. When he died the book was eventually passed on to the current owner, a surgeon who settled in the UK in 1995 after the Iran-Iraq war.

It was wrapped in pink linen for protection as the family carried it on their travels. Even today the package contains items of devotion such as a cross and a votive image given in thanks by those allowed to borrow the book when in need of spiritual comfort and inspiration.

Touchingly, in 1885, the mother of the original owner sewed up three pouches. In two she placed handfuls of earth, tokens to remind her family of their roots whatever might befall them, and in the other — a triangular scrap of white linen — there is a prayer which is to be used only if the Nareg is lost or destroyed when fleeing for safety. None of the pouches has ever been opened.

For the current owners it is a source of pride that it is on show at the Bodleian — and a source of concern that it is not safe at home. To them, the Nareg represents their deep belief and has an almost mystical power over them. It is a source of protection, still prayed over, still invoked in times of stress and happiness and an object of incalculable value, a poignant symbol of their own part in a tumultuous history and a nation’s will to survive.

Dr Gillian Evison, Head of the Bodleian Libraries’ Oriental Section, says: “Books are ambassadors of culture. With a history as turbulent as this, they are a portable part of a culture which can be taken with you and help preserve your identity.”

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.

“Armenia: Masterpieces from an Enduring Culture” runs at Oxford’s Bodleian Library until February 28.