Arrows of desire: Jerusalem has been aiming them at the hearts of pilgrims, tourists and potentates for thousands of years. And the complex sensations the stings can deliver — exhilarating, devastating — is what the Metropolitan Museum of Art captures in “Jerusalem 1000-1400: Every People Under Heaven”.

The show, which opened recently, is in classic Met epic mode: 200 objects from some 60 international collections (several in the Middle East) and a time frame in the past, with perspectives from the present through short, conversational interviews with Jerusalem historians and citizens. Much of the art itself, though, is refreshingly far from grand. With standout exceptions, such as the megaweight metalwork towards the end, objects are small or fragile or both, and look especially so in these overscale galleries: bits of fabric, scraps of sculpture, pocket-size icons, glassware, books. If the image of Jerusalem in art is otherworldly and monumental, the one projected by the show, of a city with appetites, personalities and ethnic tension, is human-scale and earth-rooted.

Three major faiths have laid claim to that city. For Jews, it’s the place where, at the End of Days, the Messiah will appear; rebuild the Holy Temple, twice-destroyed; and sort out the righteous from the rest. For Muslims, the city is sacred as the point from which the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH), after a miraculous night flight from Makkah, began a tour of heaven. To Christians, Jerusalem is a giant walk-through reliquary of Jesus’s life and death, with every street, every stone, soaked in his aura.

If spiritual links among these stakeholders are strong, so are ideological differences and sociopolitical rivalries, which can, and have, turned lethal. The show — organised by Barbara Drake Boehm, senior curator for the Met Cloisters, and Melanie Holcomb, a curator in the department of medieval art — leads us into a field of violent combat, but does so gradually, focusing at the outset on a relatively peaceable form of human competition: shopping.

|

|

Jake Naughton/New York Times |

A gilded brass Arabic astrolabe |

Medieval Jerusalem was a jumping international market town, and its prosperity is announced at the Met by an upfront show of cash: a pile of gold dinars, some dating to the 9th century, discovered by the Israel Antiquities Authority just last year. Glinting and paper-thin, the coins have a globalist history. The gold was mined in Ghana, marketed in Morocco and minted in Sicily, Tunisia and Egypt, primarily in Cairo, the capital of the Fatimid dynasty, which for a time ruled Jerusalem from afar.

What would such coinage buy in Jerusalem’s markets? Everyday things, for sure: bread and veggies; a length of Indian cotton cloth; a pretty, mass-produced clay bowl. But the pile far exceeds the average household budget. It is a fortune, more than enough for a serious splurge: for a pair of fat gold filigree bracelets, say, or an entire kitchen’s worth of high-priced pots and pans. If you, the owner, were feeling devout, or were nagged by consumer guilt, you could easily afford to commission a deluxe, mosque-worthy Quran; or spring for a first-class icon of the Virgin and Child; or pick up all 14 volumes of the Mishnah Torah — the Book of Divine Service — for home reading.

Even if you did nothing but window-shop, you would end up rich with experiences. An action-packed illustration, “Christ’s Entry Into Jerusalem”, found in a 13th-century book of Gospel readings, is a vision of multiculturalism on parade, with skin of every shade. Whether the painter, possibly a monk in Iraq, actually set foot in the city, we don’t know. But we do know that his view of its diversity was spot on.

Medieval Jerusalem had a large Ethiopian Christian population, with churches of its own. Sufis from India walked the streets. So did monks and rabbis from Greece, Persia and Spain. Francis of Assisi would have been there, if he could (a shipwreck spoilt his plans), but many of his followers arrived and stayed. Maimonides — physician, philosopher and huge Jerusalem fan — paced out the floor plan of the vanished Temple and made a hazy but exacting ink sketch of it that is, inconspicuously but astonishingly, part of the show.

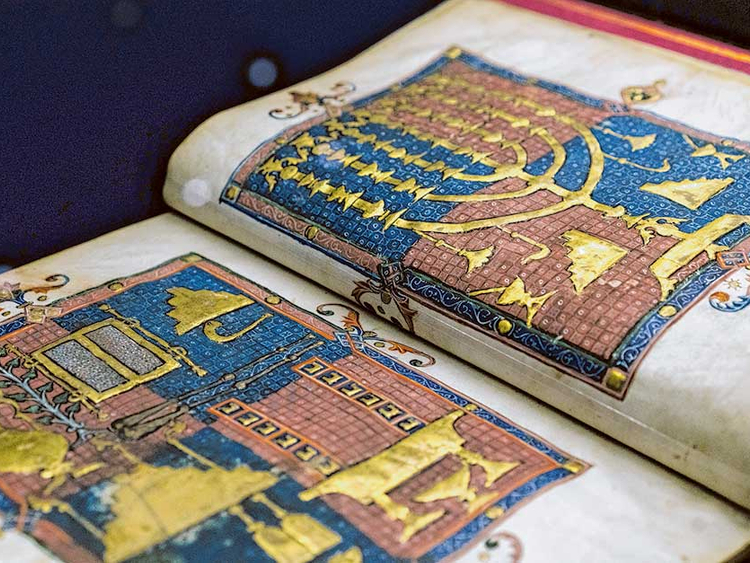

The Holy Temple may have been physically absent, but it was psychologically ever-present, for many in the form of an unappeasable yearning. And images of it, or of its celestial counterpart, appear in art. In a 15th-century illumination it stands, stolid and gold-roofed, against a line of Judean hills. Even more remarkably, it appears in perfect sculptural miniature as the ornament on a Jewish wedding ring.

|

|

Jake Naughton/New York Times |

A mosque lamp from Sultan Barquq |

By the end of the 11th century, portability and discretion were pluses when it came to religious art. Being Muslim or Jewish had become a liability. In Europe in 1095, Pope Urban II put out the call for Christians to liberate Jerusalem from people “absolutely alien to God”. Accordingly, in 1099, Crusader armies showed up at the gates and began an ethnic and religious cleansing. They slaughtered Muslims, burnt Jews alive in synagogues and cut down Christians who happened to cross their path.

The section of the show called “Holy War and the Power of Art” deals with this horror succinctly. It begins with a display of two immense steel upright swords, and a recumbent stone figure of a French nobleman who had fought in the Holy Land and now faced eternity fully armed. On the wall nearby hangs a little watercolour painting on paper of a battle in progress. The unknown artist, like an embedded war photographer, is in the thick of the fight, and we see exactly what he saw: not power and glory, but a crazy, cartoonish salad of sliced and diced heads and limbs.

To their credit, the curators pull no punches in pointing out, in their object labels and the catalogue, art’s function as propaganda, noting particularly that even obviously beautiful work can “subtly stoke sectarian violence through jewelled tones”. And beautiful art did emerge during those days. There are few books more ethereally gorgeous than the psalter made for the half-French, half-Armenian Queen Melisende of Jerusalem, its carved ivory cover of superhuman delicacy.

And there are few examples of medieval sculpture more powerful than the five limestone capitals sculpted in the late 12th century for the Church of the Annunciation in Nazareth, nearly 100 kilometres from Jerusalem. With ropy, woozy-looking figures of the Virgin and apostles leaning out of deep-cut space, the sculptures are more spooky than sublime. But they’re utterly distinctive, examples of a brilliant local hybrid style (Islamic motifs are discernible) created by a trepidatious era.

By this point, the Crusader enterprise was barely hanging on. Everyone sensed this. The church in Nazareth was left unfinished when Muslim armies under the military ruler Saladin reconquered Jerusalem in 1187. It may have been around that time that the five capitals were buried — for safekeeping? — not to be seen again until resurrected by archaeologists in the early 20th century.

Resurrection or, more accurately, vivified continuance is the theme that ends the show. Here, the three religions for which Jerusalem is a shared passion come together on equal terms. Each has its own vision of a Heavenly City, and the show has one, too: again, a kind of shopper’s paradise, but now larger than life, extra-luxe and, if you’re among those who’ve earned their way in, with everything free.

It’s quite a sight. In one vitrine you find a stash of titanic brass vessels, the biggest you’ve ever seen; in another, a lineup of mosque lamps, with glass so fine and exquisitely painted that, even flameless, they glow. A Hebrew Bible depicts the Temple treasury as an otherworldly Tiffany & Co, with menorahs and shofars of silver and gold on shelves. In a painting for a book called “The Path of Paradise”, the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) ascends from Jerusalem to a part of heaven that looks like a fabric showroom. And finally, out-glitzing everything else, one of the most spectacular reliquaries of the European Middle Ages is here. Known as “The Chasse of Ambazac”, and on loan to the Met from France, it’s a model of a Jerusalem-to-be: domed, turreted, gem-encrusted, angel-protected, it has the texture of embroidery and the heft of a steamer trunk.

The show ends, however, with something small: a page from a 14th-century Spanish Haggadah, with the Hebrew words “Next year in Jerusalem” framed by green leaves and budding flowers. The phrase, which concludes the Passover Seder, is an expression of profound longing for a city past, and piercing ardour for one to come. The Met gives us a taste of both, in the here and now.

–New York Times News Service

“Jerusalem 1000-1400: Every People Under Heaven” runs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, until January 8, 2017.