In his memoir “Istanbul, Memories of a City”, the Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk described how the ‘fragility of people’s lives… the way they treat each other and the distance they feel from the centres of the west make Istanbul a city that newly-arrived westerners are at a loss to understand...”

That puzzlement — is Turkey looking east or west? — was accentuated last month with the 12th Contemporary Istanbul fair and the launch of the 15th biennial.

The grand opening itself exemplified some of the contradictions. It was held at Esma Sultan Palace on the edge of the Bosphorous, the stretch of water that separates Asia from Istanbul and the west. The 18th century building, destroyed by fire in 1975, has been resurrected as a glamorous venue for receptions and weddings by cleverly adding an iron and glass frame within the exposed brick. The Ottoman old and the shiny new.

The city’s cultural elite gathered with such glitz and glamour it could almost have been an opening party in any of the art capitals of the west. All kisses and canapés. Very Miami.

The event emphasised how in many ways Istanbul is a confident, cultured city but perceptions of a country eager to embrace the European Union and the western values that come with it changed last year with the turmoil of the attempted coup and the fearsome reprisals carried out by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. They were further confused by the announcement in the same week as the openings that the teaching of evolution was to banned in schools and there would be an emphasis on Muslim and Turkish culture rather than a Euro-centric approach.

The traumas of last year have lingered. Ali Gureli, chairman of Contemporary Istanbul, admitted they lost 25 per cent of their contracts and that the mood had been negative and the artists pessimistic.

“This year,” he announced with renewed confidence: “We have 29 new galleries coming to the fair and 44 returning and we are staging our first outdoor sculpture park. We are aiming to be in the top five of the world’s contemporary fairs and to be a cultural modern art destination.”

So why the sense of lurking unease? Right from the first press conference, questions were asked about security and censorship which haunt Turkey and many of the more authoritarian middle eastern countries. The under secretary for the Ministry of EU affairs rejected the idea of repression suggesting instead that artists should ‘avoid censorship.’

“We are a thin skinned country,” he said. “Artists are free to express themselves but we are a conservative society. Bear in mind it is not necessarily the government that objects to art works. Often it is the people themselves. We have to be less intolerant.”

He could have emphasised his point by reminding his audience that an exhibition of the work by that arch rebel, the Chinese dissident Ai Weiwei, had just opened at the Sakip Sabanci Museum with many of his questioning works including his porcelains, several produced especially for the exhibition. No censorship apparent there.

In fact, there did not appear to be much at the fair to get under the skin of either authorities or intolerant public, unlike last year when a conservative religious group forced the removal of a sculpture of a woman dressed in a bikini with an image of the last sultan, Abdulhamid II, painted on her torso.

Instead there were many works one would expect from a commercial show anywhere in the west — splashy abstracts, an eye catching Neptune with golden boxing gloves which would grace the portico of a Russian oligarch’s second home, a wall of coloured eggs.

But Nil Nuhoglu of the newly-opened Gaia Gallery in Istanbul says: “We are trying to be edgy and provocative but we know there is a line and we take care not to cross it.”

The bronze female head spewing copper barbed wire by Gönül Nuhoglu is certainly startling and Arda Yalkin’s little dystopian ‘homes’ in Cabaret Plastique are an eerie reflection on a pill popping, impoverished society. A neurotic woman stands in her designer kitchen, surrounded by pills and giant cockroaches, touching the tip of a carving knife, another woman seems to be drowning her husband in a bath of pills.

The line is often more fiercely policed in Iran which was well represented at the fair.

Shirin Gallery, which has a branch in Tehran and New York, has had its attempt to reach out to an international audience hindered by immigration constraints since the election of US President Donald Trump.

The gallery’s founder Shirin Partovi Tavakolian says: “We know we cannot show political subjects or nudity. In Tehran they come to galleries and check. But we know how to tread carefully and we can play around with what we are saying because in Farsi words have many meanings. If questioned you can say that this word means that.”

She supports artists who might well have an international appeal such as Kamran Sharif’s copper branch suspended in front of a neon sign spelling out “Nice Dream” which symbolises an individual lost in a no-man’s land while Iman Safei employs Iranian calligraphy and symbolism with his iron “Ferris Wheel” inscribed with the equivalent of Que Sera Sera — what will be will be.

Ab Anbar, also from Tehran, fell foul of the hostility to many middle eastern artists by some western countries — or at least their governments. “We wanted to show in Basel Miami but we were rejected,” says owner Salman Matinfar. “So we offered to have an empty frame in an empty room with just a description of the work. We had a laptop ready to skype and show the work.”

They were still denied a visa.

It is a familiar story. Mahmoud Bakshi, one of An Anbar’s artists, was not able to see his work “The Unity of Time and Place” when it was shown in London earlier this year and in January the Yorkshire Sculpture Park held an exhibition by artists denied a visa by the UK immigration authority by getting them to send in their work by email.

Pride of place in the Ab Anbar booth went to Majid Fathizadeh, with “Chaos” one of the best crafted works on display at the fair. No reference to Iranian culture here, he is very European, using etching and aqua tints in an understated and classical style yet creating scenes of tumult and despair. Distinct shades of Goya.

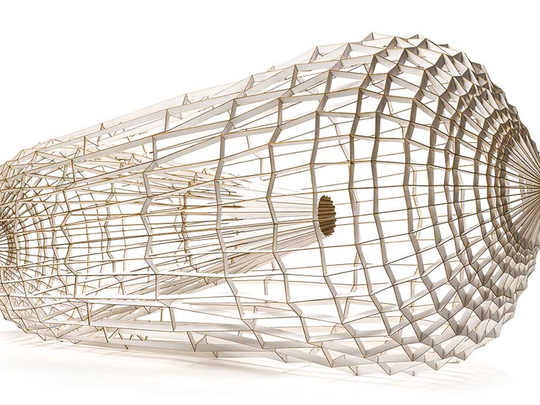

Another Tehran outfit Dastan’s Basement aims to cover the entire spectrum of Iranian modern and contemporary art with four different spaces in the city but showed only one work — that by Sahand Hesamiyan who merges western art and architecture à la Frank Gehry with islamic design and symbolism.

The gallery’s aim is to reflect the culture of the region, which for owner Homoz Hermatian includes Turkey and Iran, and highlight their shared culture.

“I am interested in what we have in common and have the conversation,” he says. “Contemporary Istanbul helps ease the politics of it all. We almost did not come last year but in the event we decided to come and give support. Now I hope they come to us.”

For the first time the fair has an outdoor space given over to sculptors with perhaps the best known the late Jannis Kounellis and the UK’s Tony Cragg.

Local artist Genco Gulan has taken a mould from a headless statue found in Anatolia and added four heads. He explained that he has followed Ottoman traditions but he seems more inspired by monsters from DC comics with his theories of radiation and the unknown perils of modern life such as genetically modified food.

Several of the galleries in the fair are well established in Istanbul such as the Pilevneli whose booth consisted of plasterboard walls with studiedly careless strips of white paint housing a lowering ceramic piece by the Belgian Johan Chreten who also figured in their new studio — white walls, concrete floors, brick work and a neon sigh exclaiming: Everyone Gets Lighter. All very much like any contemporary space anywhere in the world.

Dimarart, another prominent local player, opened a pop up gallery in a new office building with work by local man Haluk Akakce but the show “Heaven in a Wild Flower” was a scrappy affair and rather summed up by a scrawl on a wall by the artist himself: “I’m late as usual sorry.”

The works shown in the biennial which continues until November 12 are altogether more considered. The theme is “a good neighbour” and the art is spread across the city in several sites with artists from 32 countries, including Iran, Iraq, Georgia, Lebanon and Romania.

“We kept the number of artists to 56 because artists are egocentric and don’t like not to be noticed,” joked the curators, the Danish Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset from Norway.

“We wanted different cultures and different backgrounds. We chose the theme of “a good neighbour” because it seemed appropriate in the time of Trump and his wall, Brexit, the coup in Turkey and the deteriorating relations between Turkey and Europe.

“We aim to reflect problems of co-existence today where people live together in a different way from the headlines.”

And censorship? “We have done exhibitions in the world where there were limits on freedom but there was no limitations on what we could do here,” they replied. “We hope that artists can communicate better than most politicians with better perspectives and with a more human face. A biennial can be a place for people to gather together, to get inspired and to generate hope.”

One venue is the Galata Greek Primary School, in the Beyoglu district a block or two from the Bosphorous. It is an ironic choice given that the Greeks and Turks were far from good neighbours in the 20th century tearing each other apart until the Greek population in Turkey was forced to exchange with Turks in Greece.

The stairwells are dominated by four large photographic panels by Ali Taptik entitled “Friends and Changes” but the most telling work is by the Turkish Erkan Özgen whose film “Wonderland” shows Muhammed, a 13 year old boy who is deaf and mute, using only his face and hands to describe his anguish as the bombers attacked and the guns drove him from his home in Kobani, Kurdistan. His silence speaks volumes about the torment of war.

The poignant conceit of the Unknown Crying Man Museum at ARK Kultur is the transformation of a recently renovated Bauhaus style home into a memorial of pain and loneliness.

Created by Egyptian artist Mahmoud Khaled a commentary guides the visitor from room to room where the “Crying Man’ led his lonely life. From the table laid for one, the piano for solo playing, the day bed, glass trophies without inscriptions we understand his character and his complexes.

We never hear the complete story. We have to guess his predicament from clues like the old Penguin book “Love, Sex and Being Human”, next to a jar of melatonin to help him sleep. He is presumably persecuted for being gay and obviously frightened. An unworn leather jacket as used by Cairo police hangs on a peg and in the basement a line of 52 T-shirts inspired by the 52 men in identical clothing who were taken by police to court after last year’s coup.

The Pera Museum, known for its collection of works from the Ottoman era, plays host to some of the most impressive works of the Biennial.

The Georgian Vajiko Chachkhiana has framed nature scenes but brutalised them with a slab of brutal concrete. Georgia also figured in the fair with Project ArtBeat from Tbilisi. They have yet to open a gallery there, in fact, art is only on show in a few salons in the city rather than in galleries, but they use a container as a moving gallery. Credit to Contemporary Istanbul for letting them display their emerging talent which in this case comprised nine artists, mostly abstract but also with strong portraits by Maka Batiashvili,

Back to the Pera. Fred Wilson who describes himself as “African, Native American, European and Amerindian” tackles racism and the Ottoman Empire by extracting the few, the very few, black faces from classic paintings from that era and setting them separately alongside.

But perhaps the most subtly subversive are the fabrics by Istanbul-based Gozde Ilkin in her series “Inverted Home”. At a quick glance they appear to be bright floral patterns with cartoon characters but look again and the caps of police peek out from the flowers, there’s a tank and machine guns hanging like low hanging fruit and what might be fishermen in boats carrying corpses. Everywhere cockroaches. In many of the works flowers or clouds hide the faces of the figures. Threads of cotton are left hanging which increases the sense of raggedness and unease.

A little like Turkey perhaps?

That pessimism is countered by the fair’s committee member Hasan Bulent Kahrahamn who insists: “The art world continues to create its own society despite problems from the international arena or domestic politics. Art is the best answer to what is happening at a political level.”

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.