Orlando von Einsiedel is a British filmmaker whose Academy Award nominated documentary “Virunga” has been attracting the attention of some very high profile media figures, including the likes of Hollywood star Leonardo DiCaprio, who is an executive producer for the film. Former US president Bill Clinton attended the film’s screening in New York.

There was a time the documentary, which has won about 50 international awards, was struggling to get funding. “We were turned down by loads and loads of people,” von Einsiedel tells Weekend Review.

The film is about a group of people at Virunga National Park in Congo who work to save endangered mountain gorillas. It was filmed to the backdrop of a civil war and an international oil company accused of having plans to exploit natural resources. “We didn’t want to tell anyone about the oil story because we were worried about security and safety. So we were pitching a story about gorillas, people weren’t that interested,” he says.

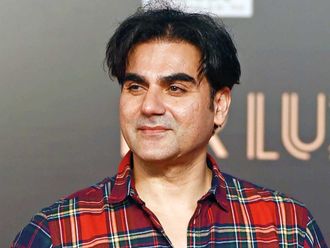

I meet von Einsiedel in south London at the office of Grain Media, the film production company he co-founded in 2006. A glance inside the office and I find his colleagues busy at work. Von Einsiedel suggests that we go outside and find a table at a little café nearby.

Before he became a filmmaker, von Einsiedel used to be a professional snowboarder, which was also his route to making documentaries. “The way you make money as a snowboarder is you get sponsored by a clothing company,” he says.

“They give you a certain amount of money and then you get a bit of extra money every time you are in a photograph or magazine. So there is a real incentive among you and your friends to all learn how to film each other and take photographs of each other. So I started to do that. I learnt how to make snowboard movies.”

He had studied anthropology at university. “I always was interested in making films about other parts of the world, other ways of life,” von Einsiedel says. His first non-snowboarding film was about refugees and asylum seekers in the UK.

He made other films in places such as the Ivory Coast and Ethiopia. “I found they were all very upsetting films to make because there never really was a happy ending,” he says. “And while making those films I kept meeting really extraordinary, amazing and inspiring people. I decided that I wanted to try and make films that were more positive.”

One film with a positive message was his 2010 short documentary “Skateistan”. It was about a group of young skateboarders in Kabul. “All the news coming out of Afghanistan tends to be very negative. Here was a story about hope. It really opened my eyes.”

It was also in 2010 I first became acquainted with von Einsiedel’s work following an unusual proposal. At the time he was working on a film on the issue of forced marriages in the UK for a TV channel. Someone from Grain Media contacted me to inquire if I would be available to work as an undercover reporter in the film.

I spoke with von Einsiedel on the phone and wrote e-mails. He wanted to see if I would be interested to meet a bounty hunter who is employed by South Asian families trying to track daughters or sons who have run away to escape forced marriages.

After some consideration I decided not to take up the offer (OK, “chickening out” of meeting a bounty hunter would be a better way of describing it). Meeting von Einsiedel five years later, I am not sure he remembers that we have spoken before, so I decide to leave the topic aside until the end of the interview.

I quiz him on some of the other films he made since “Skateistan”. They include a series of shorts from Nigeria and Ethiopia about young women who overcame great difficulties to turn their lives around. “It was actually for a charity that was operating there. They wanted to make a series of films that would inspire other young women.”

One of the short films was called “Radio Amina”, about a 12-year-old street hawker from Nigeria and her imaginary radio station. Another short film, “Aisha’s Song”, is about a partially blind woman who had to work on the streets since she was 9, until a chance encounter brings hope. Among his longer projects was a well-received film on the story of snowboarding.

Yet, of all his documentaries, it is “Virunga” which has brought him the most attention. The film secured a deal with Netflix to go out globally. It was through them that Leonardo DiCaprio also came on board as executive producer. “Netflix showed DiCaprio the film, and he wrote to me and Joanna, our producer, and said: what can I do to help? We said join the film team. And he did. He has been amazing because he has brought an audience that would otherwise not be interested in a film about Congo, about Africa, about oil.”

DiCaprio organised a screening of the film in New York, for which he invited Bill and Hillary Clinton. “They came and it was amazing. For the film to reach people in positions of real power is fantastic.”

Did Bill Clinton have anything to say about it? “He gave a little speech before the film, about the issues that the film talks about, and then he stayed for the film. He stayed for the Q&A afterwards. He stayed to talk to us after the film. It was fantastic to talk to him and Hillary Clinton.”

The film has been appreciated not just by Hollywood celebrities and senior politicians, but also within Congo itself.

“I was there last week.” Von Einsiedel organised a few screenings there. “We had a screening for the rangers and their families. I suppose they loved it, naturally because they could see themselves, their work. And then we had a screening in Goma, the capital of the province. The reaction was very positive.”

Von Einsiedel thinks many Congolese people like the film because it sends out a positive image. “It is a film about Congolese heroes. It is very rare for Congolese people to see their country portrayed in a positive way, and which has role models — African and Congolese role models. I think that is rare. I think a lot of people really respond to that.”

For von Einsiedel, one of the highlights in making the film were the gorillas. “You look into their eyes and it is very difficult not to feel a shared ancestry. You just feel as of you are looking back in time at human evolution.”

There are a little more than 800 mountain gorillas left in the world. “The orphans that live in the parks headquarters in the morning are given porridge in a mug. They hold the mug in their hands like human beings do and they drink it like human beings do. Their fingernails, their hands — everything looks just like ours. I think they destroyed a lot of camera equipment, broke the microphones and smudged the lenses. They were very difficult to film with.”

Were the gorillas dangerous? “They are very gentle. I think King Kong gives gorillas a very bad name as being violent and aggressive. Actually they are incredibly gentle creatures. They are vegetarian.”

Von Einsiedel recounts one incident. “Their forest had been bombed relentlessly for several months and no one had seen them. After several months there was a period when the rangers could get back into the forest and check on the gorillas. When they first came across the gorillas, rather than being aggressive and saying, ‘What are you humans doing to our forest?’, the gorillas surrounded the rangers and very gently reached out and wanted to touch them. And I think that really epitomises how gentle these creatures are.”

During the filming, a conflict broke out in Congo. Von Einsiedel admits to being scared. “I have spent a lot of time in conflict zones around the world but I never experienced an active combat and frankly, it was utterly terrifying,” he says. “But you draw strength from the people around you. And what Rodrique, Melanie and other people do in the investigative work, they were really taking very serious risks. They were risking their lives. And they are way braver then I will ever be.”

A particularly nail-biting scene in the film involves secret filming of people connected with the oil company Soco International. “I was very scared. Of all of that stuff it was very scary and stressful. Of course we were very concerned about Melanie and Rodrique.”

The undercover reporting brought to light some disturbing findings. “She is a very brave journalist. I think it was much more dangerous for the ranger who was doing it because his family lived there. Melanie — if it all got too much — could leave. She is from France. But he is stuck. He really risked a lot. And so did a lot of other Congolese people in this investigation because they believe in the power that this park has to transform the region.”

Meanwhile, the company has left the park. “That is partly to do with the amazing work people are working to protect the park,” says von Einsiedel. “But they have left the doors open. If the results are positive they could go back in. So the park isn’t safe.”

“Virunga” was a big part of Orlando’s life for three and a half years. He spent two years making it and the last year and a half working with the film to make it have impact on the ground in eastern Congo. “It is only in the last two or three months that I have had the time to start thinking about what might be next,” he says. “The answer is I don’t know for definite. I am very interested in doing some scripted work. But documentaries are in my blood and I will always make documentaries.”

At the end of the interview I finally bring it up. I remind von Einsiedel about the film on forced marriages he made some years back. “Yeah, I did.” And he had contacted me. “Did I speak to you? When did I speak?” It was many years ago. “What did we speak about? Remind me.” He was looking for an undercover reporter. “Yeah, we got in touch with you, didn’t we? Was it me or was it my colleague Patrick?”

I tell von Einsiedel it was him. “It was me? Yeah, I remember! What happened? Why didn’t we do something?” Well, he had wanted me to go meet a bounty hunter. “Oh my god. I remember!” he says laughing. “I totally remember. That is so funny! Yeah absolutely I remember.”

Did he find someone? “No. We chose a different story line in the end.” How did that film turn out? “We had very little money to make it but I think it is not a bad film.” More laughter. “There are some very, very brave people doing some amazing work. I was proud to be able to tell that story.”

I get the impression undercover reporting is a technique that particularly interests him. “You can’t always film everything openly. And when I think you are dealing with issues that there is a public interest in people seeing what happens in the world, you think there is a time to use undercover reporting.”

Is it a really small camera he uses for undercover reporting? “Yeah, they fit in the button of a shirt.” Is it? “I am not wearing a shirt today so you are alright,” he says.

Syed Hamad Ali is a writer based in London.