Lockwood Kipling with his son Rudyard in 1882.

Sculptor, museum curator, teacher, inveterate doodler... and father to the more famous Rudyard. Lockwood Kipling (1837 – 1911) may not have been eminent but he was a significant Victorian who did more than any other to preserve and renew Indian arts and crafts at a time when they were in danger of disappearing.

In a fascinating insight into the cultural and social environment of the continent after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, “Lockwood Kipling: Arts and Crafts in the Punjab and London” at London’s Victoria and Albert museum traces the career of this archetypal servant of Empire from his first job at South Kensington Museum (now the V&A). He taught at schools in India, collected thousands of artefacts for the museum and designed the grand outpouring of Imperial pride, the Delhi Durbar, which celebrated the installation of Queen Victoria as Empress of India.

The V&A has collaborated with the Bard Graduate Center, New York, where the show will be shown from September 15 and is accompanied by a book — a substantial work of scholarship published by Yale — which is a brilliant companion for anyone interested in the minutiae and the idiosyncracies of the empire at work — not to mention the cultural endeavours of Lockwood Kipling.

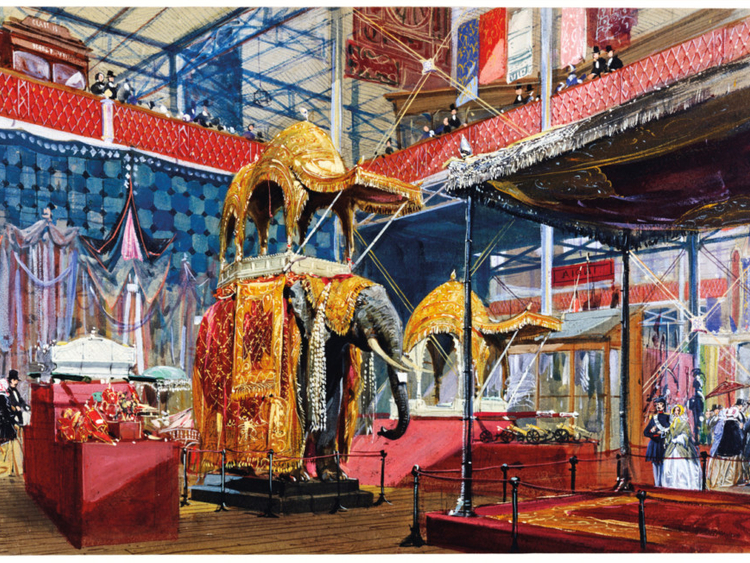

The young Lockwood seemed destined to be a preacher like his father but family tradition has it that he was taken as a schoolboy to the Great Exhibition of 1851 which was staged in the mighty glass and iron edifice that became known as the Crystal Palace. The exhibits were intended to display every symbol of Victorian greatness from steam engines to porcelain but it was, apparently, the Indian display that fired his imagination — the Queen’s too, she admitted to being ‘quite dazzled.’

It is easy to see why. Paintings capture fabulous scenes such as a life-size elephant draped in gilt and scarlet robes, a tented throne room and lavish displays of weapons, jewellery and fabrics while many of the artefacts shown in the pictures have stepped out of their frames to be displayed in all their finery — an anklet in gold, silver and enamel, a gold bracelet set with diamonds and a sword, too pretty to use surely, in steel, enamel and gold with a velvet sheath

The entire ensemble is a luxurious swirl of gold and crimson which for a lad brought up in genteel poverty must have been a moment of wonder.

When he was 18 he became an apprentice with a pottery maker in Stoke-on-Trent before moving to London and working on the decorations for the new V&A building including terracotta sculptures in which his own likeness can still be seen in a mosaic decoration overlooking the museum’s John Madejski garden.

He became involved with the burgeoning arts and crafts movement thanks to his well-connected wife Alice who knew such luminaries as the designer William Morris and was the sister-in-law to the artist Edward Burne-Jones but he found the lure of India too strong.

A Wood Carver, from a collection depicting craftsmen of the North-West Provinces of British India, by John Lockwood Kipling, 1870.

In 1865, he sailed to Bombay (now Mumbai) with Alice, who was three months pregnant, to take up a three year contract to teach architectural sculpture in the new Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School of Art. The city was enjoying a boom in the cotton trade but the couple still had to live in ‘wigwams’ thanks to a shortage of housing.

Architecture in the form of Gothic Revival was the order of the day and one that Kipling was employed to champion but he preferred to champion indigenous arts and crafts. He encouraged his students to document monuments and mosques with painted studies and urged them to be ‘grotesque and fanciful’ with their designs — as the bold heads of elephants and moustachioed men that lined the railway station testify. He found time for his own work too, creating sculptures for many of the new buildings including the Arthur Crawford Municipal Market (today the Mahatma Jyotiba Phule Mandai) which he built between 1866-71. He produced many reliefs featuring the local citizens carrying urns, washing linen, trading in the market, as well as a row of Indian birds between gargoyles of an alligator, a monkey and other creatures. The Madras Mail hailed one of the reliefs which was of a scene by a well as “the largest piece of sculpture which has ever been attempted in India … great praise is due to Mr Kipling.”

He invariably had a sketch book with him drawing endearing — and sociologically useful — scenes of workers, such as boy making a fringe for an elephant, a man weaving silk, a turbaned wood carver with chisel and mallet hammering out intricate patterns.

He patently had his frustrations with the city. He wrote: “No one thing is quite right — no masonry is square, no railings are straight, no roads are level… a strange and curious imperfection… attends everything.” Yet he also grew fond of the place. A little sketch portrays him, back to the viewer, painting a dramatic sunset over the ocean. The caption reads: ‘Bombayland — a blazing beauty of a place.’

After eight years, in 1873, he was asked to move to Lahore, the capital of the Punjab, as Principal of the new Mayo School of Art (today Pakistan’s National College of Arts) and curator of the museum.

He wrote how it was his objective to teach the Lahore school to revive crafts ‘half forgotten’ and to discourage as much as possible “the crude attempts at reproduction of the worst features of Birmingham and Manchester work now so common among natives.”

This attitude contrasted sharply with Sir George Birdwood, a prominent figure who was in charge of the government’s Indian section. Birdwood wanted to preserve old traditions as they were. The book explains how Birdwood saw India as a lost Eden, drained by industrialisation. Kipling recognised the value of that industrialisation and campaigned against British art education, arguing that the indian schools and museums had been “debased to the status of commercial factories” where a sculpture of Buddha would be represented as a “boiled suet pudding.”

In a gentle jibe at Birdwood, Kipling drew a satirical little sketch of a gent surrounded by the suitcases, trunks and the impedimenta of travel with the caption: “It’s a pity that philanthropic and sentimental old gentlemen will persist in taking off their spectacles to look at India.”

Watercolour on paper, Rudyard Kipling’s bookplate “Ex Libris” by John Lockwood Kipling, 1909

In Lahore he again enthused his pupils to be daring and sent them out to paint and record. The watercolours of the Wazir Khan Mosque with their fabulously painstaking details of its tiles, frescoes and terracotta decorations particularly inspired him as a key to revive dying crafts.

“It is not probable that we that we should at once surpass the beautiful work on the mosque,” he wrote. “But we should produce something of a distinctive and artistic character.”

A film made by today’s students captures the mosque in all its vast, crumbling glory with its towers and cupolas and resplendent Islamic imagery.

In the 18 years Kipling spent in Lahore he collected almost 200 prints and paintings by artists from his adopted home as well as Shimla and Amritsar, which his son, Rudyard, gave to the V&A in 1917, six years after his death.

Many are bold watercolours and depict Hindu and Sikh deities such as Shiva on his mount, the bull Nandi, and Khwaja Khizr. Stealing the show; Krishna and brother Balarama splendidly dressed in yellow pantaloons.

While he pursued his own interests he did not overlook the commercial potential of Indian art and how it could serve British interests. At one point he was given a budget of £3,000 by the V& A which he spent on 5,000 works such as plaster casts, carved doors, windows and screens. On display, an 18th century bay window from a merchant’s house and a late 19th century plaster cast of a first or second century bust of Buddha — miraculously found after years presumed lost by V&A researcher Sandra Kemp, wrapped up and forgotten in Salisbury Cathedral.

He arranged for Indian textiles, metal work and carving to be shown at 28 international exhibitions from Australia to the United States with the aim of advertising the excellence of the handiwork and in that way “stem the degradation of design and workmanship that was spoiling Indian workmanship under British rule.”

Fine examples remain such as chests in wood, enamel, ivory and jewels, a silver and enamel waist belt, a glittering elephant in gold, sapphires and enamel.

His career in India reached a crescendo with his work for the Imperial Assemblage of 1877 — the Delhi Durbar — which celebrated the official proclamation of Victoria as Empress of India.

As well as the banners and embroidered panels, he designed the ampitheatre itself where princes, maharajahs and heads of state gathered to watch parades of soldiers on horses and elephants. As the show’s co-curator Julius Bryant put it, it was his ‘Danny Boyle, London Olympics moment’ but the official artist hired to record the event said it looked like a ‘gigantic circus’.

When he returned to England in 1893 he and his Lahore collaborator Bhai Ram Singh reprised some of the designs from the Durbar for the Queen’s summer palace of Osborne on the Isle of Wight. Few artefacts remain — a pair of standing lamps and a fire dogs — but Kipling reported that the Queen expressed “high approval of the elaborate and beautiful work” with its white and gold decoration and its brass and mahogany.

He also spent more time designing covers and illustrations for his son, Rudyard’s books. His technique was to make a plaster cast which he photographed and were used for several scenes such as Mowgli and the Wolves from the Jungle Book and the frontispiece to Kim.

His willingness to help his son and his closeness to his wife and daughter is also reflected in the many humorous sketches he made of for them such as the train trip to the cool mountain air of Shimla and scenes from amateur dramatics they took part in as well as a little sketch of young Rudyard in a line with Dante, Homer, Shakespeare as if he was inheriting their mantle.

He wrote vignettes of Imperial lifestyle in Indian journals in which he cheerfully gossiped about garden parties, regattas and concerts but, in which, he also betrays the instinctive racism of the ruling class.

It is difficult to imagine that the same man who is so keen to encourage Indians to be artists, designers, draughtsmen, not just servants of the Raj also quoted ‘scientific’ findings of the day to avow: “people born under these skies have existed under climactic conditions … destructive of the qualities that lead to moral excellence…”

He decorated 13 dessert plates which he called: “nos ennimis intimes’ (Our Intimate Enemies) in which he satirises Indian servants. One shows a servant, arms crossed in lazy relaxation, with the caption: “They also serve who only stand and wait.” Another has one lounging, half hidden by a screen, bottle to mouth with the words: “Take, oh take, those lips away.”

Maybe his attitude simply illustrates the white man’s inherent sense of superiority in Imperial India but it by no means precludes a sense of duty he felt to his students and his admiration of the “matchless skill of hand of the best artisans.” Possibly, he was playing up to his peers in the closed British society. It’s worth remembering that the Indian Rebellion — which the British saw as a mutiny — had taken place relatively recently in 1857 and the British had become a frightened, tight-knit group, increasingly segregated from local people.

Today nationalism has replace imperialism and many in India still work to ensure survival of traditional crafts and to make them economically viable in the way he would have embraced.

Julius Bryant, who is also the book’s co-editor, writes that Kipling helped “to articulate India’s history and heritage and to repair the British romance with the ‘true’ India and to help validate Britain’s self-appointed role as a successor to the Mughal and Sikh empires.”

So while Sir George, his old rival, wanted to leave the Indians craftsmen “alone — and severely alone”, Kipling was more prescient.

He wrote: “It is as easy to seclude the Oriental designer from foreign influences as to keep the sea out of a harbour with a mop.”

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.

Lockwood Kipling: Arts and Crafts in the Punjab and London will run at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London until April 2.