Mumbai: All her life, home for Robab Nallwalla has been a one-room flat in central Mumbai, a space she shares with her parents and her brother - and more recently, her brother’s wife.

The single room, similar to nine others on the dingy floor with no lift, was cramped and noisy, not a place she could invite friends to.

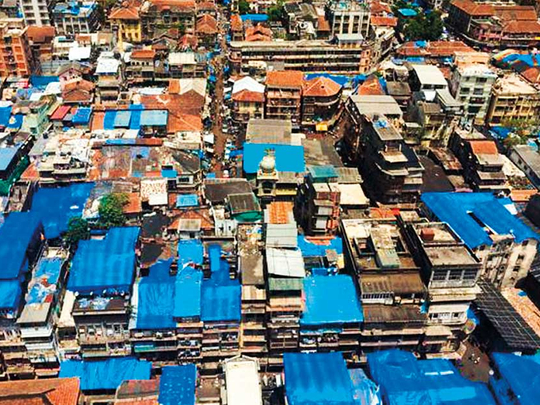

The neighbourhood, Bhendi Bazaar in the heart of India’s financial hub, was not one she could boast of, either.

That is about to change as the 150-year-old quarter - a colloquial twist on “behind the bazaar” as it was known - embarks on a unique community-led modernisation that could be a model for inner-city redevelopment across India.

“We have often felt embarrassed to say where we live; we have even heard of marriage proposals being rejected for people who live here,” said Nallwalla, 24, a PhD student.

A seachange

“But now I am very excited about this project. I am looking forward to having our own toilet, for my parents to finally have their own room, and being able to call people over,” she said.

The Nallwallas are among 3,200 families and 1,250 businesses who populate bustling Bhendi Bazaar, with its narrow streets bursting with shops and vendors selling everything from hardware and yards of colourful cloth to antique furniture.

The dilapidated low-rise buildings in the 16.5-acre (7 hectare) site will make way for high-rise towers, wide streets, parking lots and green spaces.

“It is a shame the community has lived like this for so long,” said Abbas Master, chief executive of Saifee Burhani Upliftment Trust that is funding and overseeing the project.

Many residents belong to the tight-knit Dawoodi Bohra Muslim community, who have made the neighbourhood their own with mosques and restaurants serving familiar food.

Their leader, the late Syedna Mohammad Burhanuddin, spoke of improving the neighbourhood and making owners of tenants.

“His Holiness was very disheartened by these conditions, but there were no policies then that could enable a redevelopment,” said Master. “Now that there are, we want to do our duty for the betterment of the community.”

Migrant workers

The 250 brick and wood buildings crammed into Bhendi Bazaar were initially made for migrant workers who flocked to the busy port and textile mills in Bombay, as the city was then known.

The area also drew traders in wood and textiles from the neighbouring state of Gujarat.

Slowly, the workers brought their families over, but stayed put in the cheap, dormitory-style rooms measuring about 250 square feet (23 square metres) with shared toilets.

Through it all, the buildings became increasingly dilapidated as rents stayed low at Rs20-Rs30 (less than 50 cents) a month.

Landlords refused to upgrade and tenants, with few affordable options in the city, added amenities such as air-conditioners while lining up outside the common toilets. A single tree breaks the jumble of buildings.

It is a familiar story in many of India’s congested cities, where thousands of colonial-era buildings fall under an archaic rent-control law.

Many of these buildings, with their exposed wiring, sagging staircases and broken sewage pipes, have been declared unfit to live in. But tenants who have lived there for generations oppose any plans that might uproot them or raise rents.

In Mumbai, which has some of the world’s most expensive real estate, the situation is particularly dire: more than 60 per cent of its 18 million people live in slums and informal settlements.

New policies in recent years, including a state plan for “cluster development” of slums and tenement blocks, and a federal scheme to revitalise 500 cities including Mumbai, have provided more leeway for redevelopment.

“It is very difficult to get all stakeholders to agree to a plan, so there are few success stories, and none of the scale of Bhendi Bazaar,” said Anuj Puri, chairman of real estate consultancy Jones Lang LaSalle Residential.

“Redevelopment is a process of urban renewal. But it is also important that the cultural fabric of the community be preserved,” he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

The Saifee Trust intends to do that, said Master. The towers, with sweeping views of the city and of the Arabian Sea, will house shops on the ground floor and two additional floors. The rest will be given over to residences.

Apartments will be 350 square feet each, with a bedroom and two attached bathrooms, with a space even to hang the washing, but in an “aesthetic manner”, Master said. All residents who have lived there or had shops before 1996 will get ownership titles.

The towers will feature elements of Fatemi architecture, with arches, domes and jalis, or carved latticework. They will also have sewage plants, solar panels and rainwater harvesting.

Eighty per cent of the land will be used to house existing tenants, while a fifth will be sold to meet an estimated cost of Rs40 billion (Dh2.2 billion) in a project that is expected to take a decade.

“Bhendi Bazaar has a special place in the city, and it is our duty to conserve that character, our culture and sense of community,” Master said.

“At the same time, we need to evolve. This could be a model for urban rejuvenation elsewhere in the country.”

On a recent weekday evening in Bhendi Bazaar, the area was a cacophony of honking horns and vendors calling out their wares, as the call for prayer sounded from a mosque.

Men and women rushed about on foot and on motorbikes, buying fruit and fried dishes for the iftar meal to break their Ramadan fast.

For the Nallwallas, the celebratory mood has more meaning, even if they have to wait about five years for their new home.