It’s 1630 and King Pooradam Thirunal-Devanarayanan of Chembakassery in central Kerala (now Ambalapuzha), and his general, Mathur Panicker, are gearing up to counter a threat from the feudal lords of Odanadu (now Kayamkulam). Chundan valloms or snake boats, 110 feet long and commanded by local chieftains, Nair and Christian padayalis — warriors hailing from nearby villages — are assembled to showcase Chembakassery’s might.

The legacy lives on

Whether the kingdom was saved by its naval troops or not is history, but snake boats similar to the ones they used continue to be a part of Kerala’s culture, thanks to boat races staged across the backwaters of the Vembanad Lake in Alleppey.

Dr Naduvattom Gopalakrishnan, an expert on Kerala’s history and culture, and professor emeritus at Malayalam University in Malappuram, says, “Chembakassery was constantly under threat from Odanadu and Venad [earlier Travancore]. The need to find a solution [to provide strategic military backing] led to the development of snake boats.”

An exotic sport

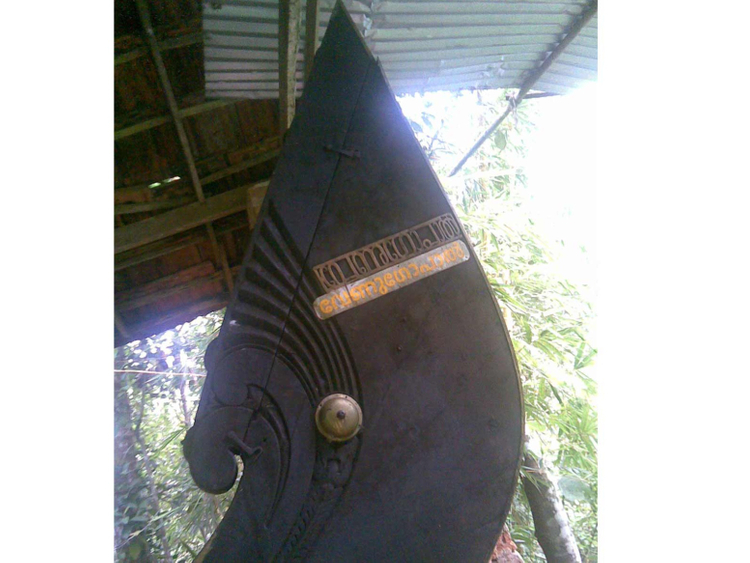

The king invited the public to design better naval vessels and Vengayil Narayanan Achary, a carpenter, presented a model based on the kothumbu — the shield that covers the inflorescence of the coconut palm. “It gave Chembakassery the upper hand over its enemies. The sharp-beaked front helped the boats crash into its opponents,” says Dr Gopalakrishnan.

Velayudhan Panikkassery, an academic who has penned books on Kerala’s history, says, “An ideal snake boat could hold 140-160 soldiers, and during prolonged warfare they were accompanied by veppu valloms [boats on which food was cooked]. Another boat used was the iruttu kuthy, for spying.

“Snake boats had no ritualistic role then, although they were used as escort vehicles during the idol consecration ceremony of [the temple at] Ambalapuzha, which marks the annual Champakulam Moolam Boat Race.”

These boats were used for social events when they were not in use by the navy. Today, they are seen across central Kerala with oarsmen warring against each other as part of an exotic sport.