A woman stares enigmatically at the camera, She wears a tight green jumper and jeans. In her left hand she holds an arm, covered in freckles and wearing a wrist watch. It is stretched across her body.

It is her prosthetic arm.

This is one of the unnerving images that make up one of the most compelling exhibitions held in the United Kingdom in the year of the 100th anniversary of the First World War — “The Sensory War, 1914-2014” at Manchester Art Gallery.

It examines the art of war from the outbreak of hostilities in the summer of 1914 to Afghanistan by demonstrating the relationship between the senses reacting to the violence of conflict to the work of the artists. The 173 works on display are divided into ten sections such as Militarising Bodies, Manufacturing War; Pain and Succour; Shocking the Senses.

The core of the exhibition owes a debt to the first director Lawrence Haward who took over at the gallery in July 1914 on the eve of the declaration of war on August 4 and instigated a collection of war art. He wrote that artists “are affected by the changes in the condition of the world which the war produces” and argued that war is sensory and emotive and the artist will “reflect that world and the human emotions it arouses”.

Every painting, photograph, video on display in this dark, uncompromising exhibition substantiates his argument.

The woman holding her prosthetic arm is one of the figures under the heading Rupture and Rehabilitation, which shows in unsparing detail the torn limbs and destroyed faces that are the legacy of war. Dawn Halfaker was a West Point graduate who had her right arm amputated after a grenade attack in Iraq. Her picture was taken by US celebrity photographer Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, who was commissioned to do 13 portraits in 2006 as part of an event to highlight the traumatic aftermath of conflict.

Just as uncompromising is Marine Wedding (2006) by American Nina Berman. A terribly scarred soldier and his new bride take their vows but her eyes tell the story — this is not the man she promised to love until death; this is a man she cannot recognise. The marriage lasted only a few weeks.

In the same section are water colours by Herbert R. Cole, which are unsparingly factual representations of soldiers’ faces who have been cruelly disfigured by war and which were painted for the Royal College of Surgeons and not meant for public viewing. One can see why.

It’s the faces that haunt. In Shocking the Senses, Otto Dix’s series of lithographs, “Der Krieg” (1924), shows faces crazed with terror such as “Wounded Man Fleeing — Battle of the Somme” or “The Madwoman of St. Marie-a-Py”. In Chemical War and the Toxic Imagery the figures in Louis Raemaeker’s “A Poisonous Gs Attack on Canadians in Flanders” (1918) shows the victims gasping for life while Iranian Sam Samiee’s poignant “Sleeping Children” (2012), refers to the death of 5,000 Kurdish civilians who were killed or maimed by Saddam Hussain’s gas attack on Halabja. The sheer ugliness of the gas warfare is symbolised by the grotesque images of gas masks by Canadian artist Sophie Jodoin in a series of conté drawings (2008).

“Bombing, Burning and Distant War” woodcuts by Kathe Kollwitz (The War 1922-23) shows us the innocent victims; the widow hugging herself in grief, the parents holding each other in despair at the loss of their son.

The Japanese hibakusha were the survivors of the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki who were asked to record their memories of the attack in the 1970s. The results are invariably crude but harrowing, such as the child-like drawing of a hand whose fingers are melting in the heat by Akiko Takakra, who was 51 when he drew it, and “Charred Body”, its hands reaching to the sky by Masato Yamashita, who was 52 at the time.

One of the most significant artists in the exhibition is the British Futurist and official war artist C.R.W. Nevinson (1889-1946), who was initially excited by “the beauty of the strife” but later lamented: “My former life seemed to be years away ... I felt I had been born in the nightmare. I had seen sights so revolting, shrieks, pus, gangrene and the disembowelled.”

He captures the dehumanising effect of the war machine most potently in the section Militarising Bodies, Manufacturing War with the massive, still, threat of “A Howitzer Gun in Elevation” (1917), “The Explosion” (1916), the vivid blast on a horizon, and “Returning to the Trenches”, (1916) which reduces the men to marching cyphers.

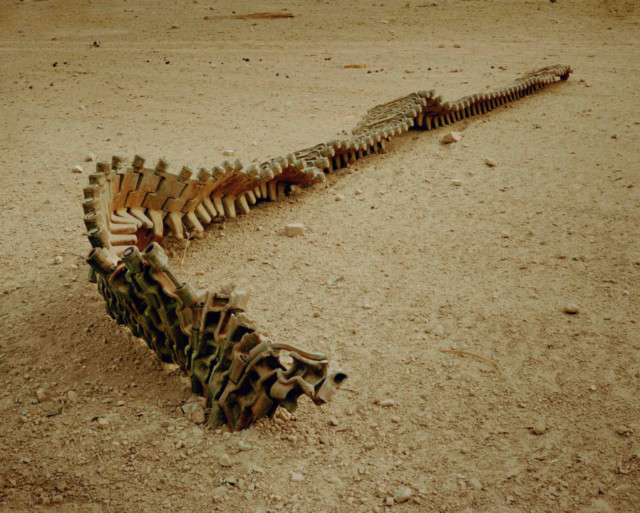

There are few figures, dead or alive, in the paintings of Paul Nash and Willam Orpen, or indeed Nevinson, but the very emptiness of figures in the landscapes is what gives them such a visceral impact.

Paul Nash captures the mud, the blood, the skeletal tree stumps of the front, with desolate works such as “The Field of Passchendaele” (1917) and “The Landscape; Hill” (1918). Nevinson’s “A Front Line Near St Quentin (1918), is an empty scene only relieved by a foreground of barbed wire and fluttering poppies. William Orpen’s bleak “The Shwaben Redoubt” (1917), looks like a snow scene but the white is the chalk of the Flanders fields chewed up by a million boots.

So graphic are they that it is as if the stench of gas and gangrene leaks from the canvases.

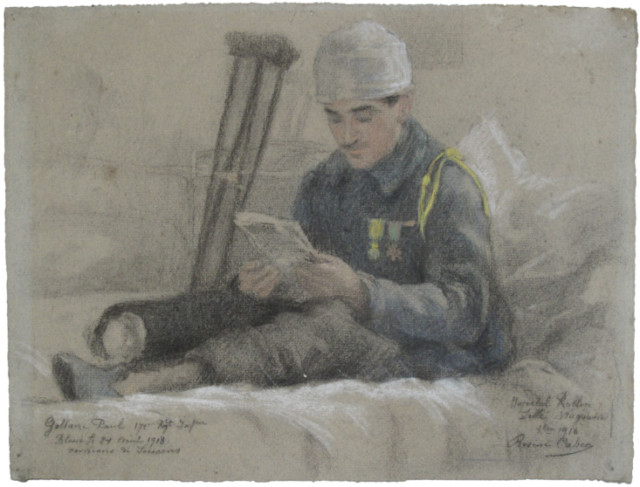

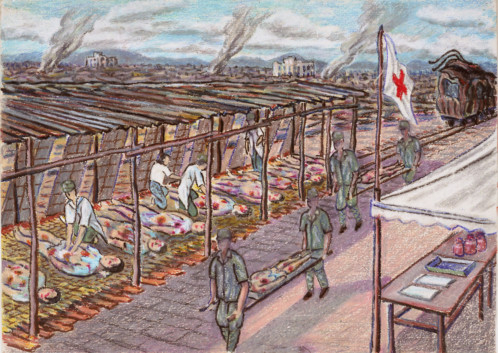

There is little hope here. In the section Pain and Succour, two doctors who became artists are set side by side — Henry Lamb’s “Advanced Dressing Station on the Struma, 1916” (1921). which depicts soldiers standing around helplessly while a doctor administers aid — or maybe the last rites — to a wounded man, and an unfinished painting by Henry Tonks, “An Advanced Dressing Station in France” (1918) illustrates the chaos of the battle front, the stretchers, the walking wounded, the ruins in flames.

Some of the categories blur, particularly the landscapes which can be made relevant to more than one section. Henry Tonks’s 1915 work “Saline Infusion”, which has the medical team gathered around a wounded soldier — who appears sprawled like Christ on the cross, is in the category Rupture and Rehabilitation. It could well qualify for Pain and Succour. Muirhead Bones’s “Casualties; Tanks drawn at Flers on the Sommme” (c1917) and Frank Bramgwyn’s “Study for a Tank in Action” (1925-26), which are sited in Embodied Ruins would not be out of place in Militarizing Bodies, Manufacturing War.

But that is a quibble. The net effect is to capture the subject of war, and the pity of war. And that it does uncompromisingly.

It’s hard to find a glimmer of optimism. Under the heading Ghostlands, Loss, Memory and Resilience, a wry commentary on video by Vietnamese Dinh Q Lê, survivors of the Vietnam War tell their stories in “The Farmers and the Helicopters” (2006). They recall the terror the helicopters brought to their country, interspersed with scenes from of the US airforce bombing the countryside. But there is a pragmatic conclusion; some of the old ‘copters are being used as a crop sprayers. The world moves on.

And there is one symbol of resilience . In the last image of the show, photographer Simon Norfolk’s “Balloon Seller Outside a Former Teahouse” (2001) has a solitary man standing in a blasted landscape with a clutch of balloons for sale. Maybe a child will buy one.

But that’s all by way of hope. This show is as sombre as its subject. And that’s a compliment.

The Sensory War 1914-2014 runs at the Manchester Art Gallery, UK, until February 22.