Bengaluru: Every month, student blogger Mithun Balraj organises a get-together for gamers and developers in Koramangala, Bengaluru. When these informal gatherings began a year ago, five or six people came along — now there are over 30 and interest is growing.

Some pop in just to chat about the games they’re playing, others show off prototypes of their own projects; they all want to discover new titles. “I brought in the sword-fighting game Nidhogg last week,” says Balraj. “It was great, but we got a little bit carried away. The bar owner told us to be quiet because the other customers were trying to watch the cricket.”

This cultural clash between old and new India is an effective symbol of where the country’s video game industry is right now. For years, giant Western publishers exploited it for its intelligent and cost-effective workforce, outsourcing specific graphics tasks — like modelling realistic racing cars — to local studios that basically worked like factory production lines. But over the last two years things have started to change.

A new generation of talented and creative Indian developers has grown up, inspired by the thriving independent development scenes in the US and Europe. Spurred on by the success of hits like Doodle Jump, Angry Birds and Cut the Rope, they don’t want to craft digital assets for other people; they want to create their own games.

Now they’re getting their chance — and it’s thanks, in part, to an important change in Indian society: the birth of a Western-style start-up culture. “It’s true that India’s development community began with outsourcing studios employed by Triple A publishers,” says Abhinav Sarangi, co-founder of Mumbai-based studio All In A Day’s Play.

“However, in the last two years it has changed, mostly because of the emerging start-up community. We have Flipkart, which is India’s Amazon, we have OlaCabs, which is India’s Uber — these companies have shown that technology-driven concepts can flourish here. That has trickled down to the game development community, so we’re seeing a lot of small studios springing up and taking risks. India has traditionally been a risk-averse society; we were told: ‘if you don’t take a job in a big company, you probably won’t get married.’ But the tech sector has opened up really quickly. Studios are now saying: if other tech start-ups are doing well, why can’t gaming?”

The growing strength of this nascent development scene is immediately obvious at this April’s Pocket Gamer Connects conference in Bangalore, a two-day smartphone gaming event held in the city’s luxurious Lalit Ashok hotel. It’s the first get-together of its kind here, and the 500 attendees include representatives from big players like Intel, Amazon and Google as well as smartphone gaming giants such as Rovio and Zepto Labs.

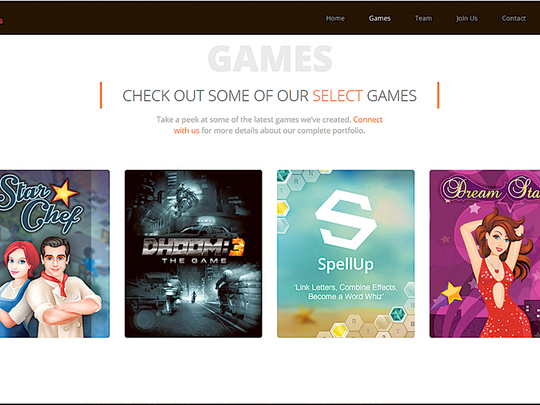

They’re basically here either to figure out how to get their brands in front of this vast new audience, or to suss out the local talent. And there are plenty of success stories to uncover. There is 99Games, based in Udupi, which has developed 15 titles for both the domestic and global market, including recent success, Star Chef, a fast-paced cooking action game with 40,000 daily users and revenue growing 25% a quarter.

There is Yellow Monkey Studios, a relative veteran at eight years old. Its latest title is the sleek, tile-sorting puzzler, Socioball, which features an ingenious map editor that lets players create their own levels then share them via Twitter. “The indie scene has picked up a lot in the past three years,” says founder, Shailesh Prabhu, who has helped to set up an online community of small indie studios which now has over 600 members.

“With the advancement in development tools, a lot of studios have gained the ability and confidence to produce games that can match up to the global quality standards.” The co-organiser of Pocket Gamer Connects, Reliance Games, is a publisher and developer in its own right, specialising in movie licenses. It has seen over 70m downloads of smartphone tie-ins like Hunger Games: Catching Fire and Pacific Rim.

Manish Agarwal, chief executive of Reliance Entertainment — Digital, sees it as a duty to promote local studios. “Those teams need context and community,” he says.

“That’s how we learnt: by travelling, meeting people, setting up appointments, it’s a continuous process. We were motivated to organise this event because India is just not in the diary for anyone. When we go to international conferences, people look at us as though we’ve come from Mars — they think of China, Japan and Korea as gaming markets, but they don’t think of India. The appreciation for the talent here was not really there at the global level. We need to showcase it.”

That determination to build something, to gather a community and to develop talent, is everywhere here. Ubisoft India’s managing director Jean-Philippe Pieuchot is working with local universities to improve games education; Chennai-based developer Growl Studios has set up game design workshops at colleges around the country. Young coder Himanshu Manwani, whose brilliant, brutally challenging platformer Super Nano Jumpers won the event’s Very Big Indie Pitch competition, is determined to help foster the emerging scene: “When I go back to Bhopal, I’m planning to visit colleges and universities and tell students, this is a viable career option. If you love making games, just do it.”

Meanwhile, smartphone sales are exploding here: there are 120m owners in India already and analysts predict that by 2016, this market may be bigger than the US. Everyone is after a piece of that action. Disney has a combined movie and game development studio in Pune, where Ubisoft has also been since 2008. Zynga is in Bangalore, updating the Farmville franchise. Rovio has been in Delhi for two years. They all face some big challenges if they want to make money here.

This is a market with barely 8% credit card penetration, and where over 90% of mobile users are on prepaid contracts, so the Western model of relying on customers to make seamless in-app purchases through online app stores isn’t going to work. The networks would struggle with the data load anyway: much of India’s mobile infrastructure is still operating at 2G speeds.

On top of that, people just don’t have the disposable income to spend money on in-game trinkets and power-ups. “You can’t expect a person who’s earning $10 a day to spend 99c on some item in a game,” says Agarwal. Some think the answer is for Apple and Google to change their App Store pricing structures, and to shift to a carrier billing method that better suits the Indian customer. Others are looking to innovate the revenue option that utterly dominates the mobile gaming sector in India: ad-funding. Disney Interactive India, for example, is working on a model where if a smartphone owner downloads a game they can get a free taxi ride with a partner company, worth around Rs300-Rs400.

There are also third-party wallet companies like Paytm and MobiKwik that may provide a more reliable method of monetising this huge gaming audience. There’s more to the market than working out to exploit the infrastructure, though. India’s vast and rich culture has barely been tapped by developers, beyond the obvious influx of cricket sims, puzzles and card games. Studios need to be exploring that, both for domestic and global audiences. Ubisoft, for example, is heavily marketing its smartphone music game Just Dance Now, to Indian phone owners, tying up endorsements deals with Bollywood stars like Shah Rukh Khan, whose hit song India Waale is included in the game.

The company is also handing a percentage of the development duties on console release Just Dance 2016 to the Pune a studio — a major coup for what was once a typical outsourcing and porting house. A range of Bollywood numbers will certainly feature. Rovio, too, is seeking to exploit the creative talent and cultural appeal of India. “There are lots of amazing colourful festivals,” says Peter Vesterbacka of Rovio. “There is potential in exploring and leveraging the many interesting artforms and designs that have originated here.”

The company has already tweaked Angry Birds for China, creating special content around the New Year and the Moon festival. It is also about to release Angry Birds Fight, a competitive two-player match-three puzzler targeted at the Japanese market and designed by a local studio Kiteretsu. India is next. “It’s important to have a deeper understand of the local culture,” continues Vesterbacka. “That’s why we have an office in Delhi. Our goal is to be the leading Indian brand — wherever we go, want to be more local than the locals.”

Local studios see the potential too, of course. “The next step is to see Indian-themed content getting a global audience,” says Sarangi. “Year Walk by Simogo is a great game about Swedish folklore and it was enjoyed throughout the world. We’re working on something similar with a specific India story, and with world-class art.”

Gradually then, the whole culture of game development is reversing in India. Once used for its cheap, skilled labour, it is now in a commanding position to compete in the global smartphone gaming market. The situation has led to some ironic new business practices. On one afternoon during the Pocket Gamer Connects event, I get talking to Shehzaad Nensey of small Mumbai-based studio, On The Couch. Their game Rooftop Mischief has been produced by a small team of eight artists, designers and coders. “What about the music?” I ask casually. “Oh,” replies Nensey, almost dismissively. “We outsourced that to the UK.”

_ Guardian News & Media Ltd,