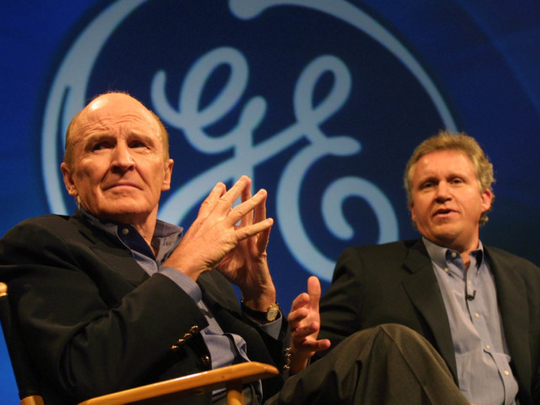

For “Fortune” magazine in 1999, Jack Welch, then General Electric’s chief executive, wasn’t just the country’s best executive, or the manager of the year, but nothing less than the best manager of the 20th century, “far and away the most influential manager of his generation.”

Welch himself was more circumspect. “My success will be determined by how well my successor grows it in the next 20 years,” he said at a management conference that year.

Eighteen years later, with the announcement that Welch’s hand-picked successor, Jeffrey R. Immelt, would step down as GE’s chief executive, the verdict would appear to be in.

“Given how horrendous the stock performance has been for so many years, the most amazing thing is why the board didn’t act sooner” to replace Immelt, said Charles M. Elson, a professor and director of the John L. Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware.

Scott Davis, a Barclays managing director, said on CNBC that Immelt’s tenure was “an unmitigated disaster for shareholders.”

Welch brought much needed energy and charisma to the chief executive’s job and streamlined GE’s bloated bureaucracy. Had he stayed on through the financial crisis, perhaps he would have recaptured the growth that eluded Immelt.

But hardly anyone considers Welch, now 81, a management role model anymore, and the conglomerate model he championed at GE — that with strict discipline, you could successfully manage any business as long as your market share was first or second — has been thoroughly discredited, at least in the US.

No wonder, given the performance of the company’s stock over the past 10 years. GE shares dropped 25 per cent during that period, in contrast with a 59 per cent rise for the S&P 500. The rival industrial conglomerate Honeywell’s stock has more than doubled, and Danaher’s has tripled. United Technologies gained 67 per cent.

Nonetheless, Immelt remained one of the country’s highest-paid executives: $21.3 million in 2016, $33 million in 2015, and $37 million in 2014. Even without a formal severance package, Immelt, 61, will get an additional $211 million when he retires, Fortune estimates.

“I’m a long-term GE shareholder,” Elson said. “The bottom-line is, I did poorly and he did very well.”

Immelt pointed to the increased strength of the company’s industrial businesses, their competitiveness and large market shares. “I’ll say that will stand the test of time,” he said. “Let other people make their own judgements.”

Immelt’s defenders have pointed out that he had to contend with the collapse of the tech bubble, the September 11 attacks and the financial crisis, all circumstances beyond his control. But so did the chief executives of every other major company.

“About the best that can be said is that he enabled GE to survive through a difficult time,” said Bruce Greenwald, professor of finance and asset management at Columbia. “But he never really understood how to create value through growth.”

And he inherited “a highly inflated stock price,” Greenwald said, thanks to Welch’s aura and lofty expectations that probably no one could have met.

As Aswath Damodaran, a finance professor at the New York University Stern School of Business, put it, “It’s always tough to follow a legend.”

Suffice to say that Immelt won’t be writing a book like Welch’s national best seller, “Jack: Straight From the Gut”, to celebrate his tenure at the helm of GE. But ultimately, it may be the much-lauded Welch whose reputation emerges more tarnished.

“Jeff Immelt brought his best every day for 16 years,” Welch said in a statement.

Immelt tacitly repudiated the Welch model himself, moving to dismantle parts of the sprawling GE empire by getting rid of NBCUniversal and the once-too-big-to-fail GE Capital. The problem, many critics said, is that he didn’t do so nearly fast enough.

“I don’t think Jack Welch was ever as good as he was made out to be,” said Damodaran. During Welch’s tenure, “he benefited from the growth of financial services in the American economy and the growth of GE Capital. “That’s what made it untouchable for so long.”

That strategy backfired in 2008, years after Welch had left, with the arrival of the financial crisis. “It turned out GE had no competitive advantage in financial services,” Damodaran said. “If anything, their risk controls were even worse” than those at other large financial institutions. Warren E. Buffett had to come to the rescue with a $3 billion infusion.

Damodaran said he warned GE executives in 2005 that complexity could become a problem. “If you wanted to create a valuation hell, it would be GE,” he said. “It was too complex by design, growing through numerous acquisitions. I told them back then, ‘You’re getting away with this now, but if there’s ever a crisis, it will come back to haunt you.’”

Both Greenwald and Damodaran said the Welch conglomerate model had been thoroughly repudiated, so much so that there is a widely recognised “conglomerate discount” applied by investors to the stock prices of companies consisting of businesses with no obvious synergies.

Activist investors have pounced on this to urge the break-up of disparate operations, and GE itself has been the target of the activist investor Nelson Peltz.

“Specialisation is something that provides real value,” Greenwald said. “If you’re a conglomerate, by definition you’re not specialised.”

Even companies like Honeywell and United Technologies “aren’t trying to do everything,” he added. “They have areas of specialisation.”

Damodaran said few of the world’s conglomerates, if any, are superstars.

“They may be doing better than GE, but they all suffer from similar problems,” he said. “They’re not nimble and adaptable. It’s much harder to be a conglomerate today than it was 20 or 30 years ago.

“The Welch model is certainly dated. Maybe it’s still used in a few old-line manufacturing businesses, but not in the rest of the economy, where a start-up can destroy your business.”

Even though Immelt deserves praise for abandoning the Welch model, Damodaran said, he did it much too late. “They’d be much better off if they’d started sooner,” he said.

In a statement, a General Electric spokeswoman said, “Today, GE is a more focused industrial company with strong growth opportunities in the long term.”

GE shares rallied the week on news of Immelt’s departure, largely on hopes that his successor — John Flannery, a company veteran — will embrace that logic. He promised a “comprehensive review” of all GE businesses to be carried out “with speed, urgency and no constraints.”

That left investors salivating for more divestitures or spin-offs. “Does anyone really think there are any synergies between medical equipment and jet engines?” Greenwald asked. “A complicated, specialised business like medical equipment would be much better on its own.”

More divestitures may well result in pretty much the same GE that Welch inherited, which is “a boring, mature company,” Damodaran said. “This isn’t a company that’s going to work miracles.

“Even if well run, about the best GE can hope for is to grow at the rate of the economy. But that may be the best-case scenario. If it tries to rediscover its youth, that would make me nervous.”

— New York Times News Service