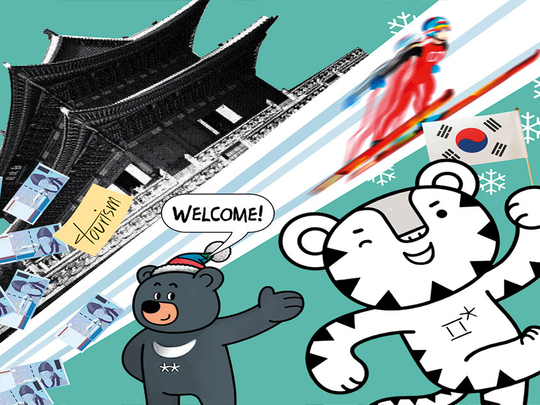

The Winter Olympics has enjoyed a strong first week of global attention, reflecting the estimated $13 billion (Dh47.81 billion) that South Korea is projected to have spent on the landmark event. At a time of geopolitical turbulence in the region, the Games offer a remarkable opportunity for the host nation to present a positive image to the world enabling a potential brand makeover for the country.

A key goal of the organisers is to present a vision to international public of a modern, vibrant, stable democracy that is a prime destination for future investment and tourism. And with a multi-billion audience watching, the nation is hoping to capitalise on a first class opportunity to showcase its credentials after a troubled time in 2017 that saw tensions rise — sometimes dramatically — with the North.

While the nuclear stand-off on the peninsular remains, the Olympics have already brought about a highly unexpected geopolitical dividend. That is, at least temporarily, relations between North and South have improved and — remarkably — the two sides have even entered a number of joint teams, which are competing at the Games.

Two major questions arise, going forward, that will determine whether a financial dividend can be delivered too to South Korea.

Firstly, can a country’s reputation be enhanced in the same way as a corporate (or other organisation) might do? And, secondly, can this have a positive, significant, and sustainable national impact?

On the first issue, competition for the attention of stakeholders like investors and tourists is intensifying, and national reputation can therefore be a prized asset or a big liability, with a direct effect on future political, economic, and social fortunes. Boosting country reputation is therefore an ever-common ambition of nations in what is an overcrowded global information marketplace, and a number of countries have successfully used the Olympics to positively differentiate themselves to the world, including Spain post the 1992 Barcelona Olympics and Australia post-Sydney 2000.

Yet, the simple fact is that many nations fail to fully capitalise, reputationally, politically, or economically, upon hosting the Olympics and other major sporting events like the Commonwealth Games and football World Cup. One only has to recall legacy images of abandoned and underused newly-built Athens 2004 Olympic stadiums, whose inflated cost helped contribute to Greece’s massive public-sector debt, to appreciate that countries do not always get this right.

Moreover, on the economic front, numerous studies have indicated that ‘legacy-driven’ Olympics growth is often over-hyped. In 2012, for instance, Citibank, found that in nine of the last 10 Summer Games, gross domestic product tended to rise in host nations in the run-up to the event, but then receded in the two quarters afterwards.

To maximise prospects of Korea benefiting, it must pursue a concerted reputation, political and economic strategy that aligns all key national stakeholders (across the public, private and third sectors) around a single, coherent vision for its country brand. This exercise should not just be the preserve of tourism agencies, let alone governments, but must involve the private and third sectors too.

A good example here is the ‘New Zealand Way’ Initiative that helped transform global perceptions of that country in the 1980s and 1990s. New Zealand was in the midst of a difficult economic climate during much of the 1970s and 1980s, partly caused by the country’s loss of preferred trading status with the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth — amongst the nation’s then major export markets.

In this context, the New Zealand Way initiative helped transform perceptions of the country by building a destination brand for outdoor sports and tourism, in part, by leveraging the hosting of events like the 1987 Rugby World Cup and the 1990 Commonwealth Games. Here, the untapped potential of the country’s natural environment was recognised and indeed subsequently showcased in films too like the Lord of the Rings blockbuster trilogy.

And it is no coincidence that the New Zealand tourism sector has enjoyed a long boom. For instance, visitor numbers from the United Kingdom increased by around 60 per cent between 2001 and 2006 alone.

Building upon the growing international appreciation of the country’s unspoiled natural environment, and in the face of the loss of its preferred trading status with the UK and the Commonwealth, New Zealand recognised that a strong country reputation for quality agriculture and produce would be hugely beneficial if it was to better compete in global markets. The subsequent success of the country’s agricultural sector, which has also become more competitive and efficient, is symbolised by the fact that it now accounts for around one third of global dairy exports — that is twice Saudi Arabia’s share of the world oil exports.

The New Zealand example underlines how even a relatively simple, unified country brand-vision can be powerful. To be sure, the country is not unique in just having a beautiful, scenic environment, but has also managed to capture the world’s imagination with its consistent branding that has put outdoor pursuits and natural values firmly at its core as epitomised, for instance, by the ‘New Zealand 100% Pure’ slogan.

This is a lesson that South Korea would do well to learn fast as it seeks to capitalise upon the Olympics. In the midst of the hurly burly of the next few weeks, the long-term opportunities of the Winter Olympics should not be sidelined. As with New Zealand, a key part of this work must connect Pyeongchang’s hosting of the Winter Games to a wider story that showcases South Korea’s real strengths as a nation so as to increase favourability of international perceptions of the country — politically, economically and socially.

Taken overall, the medium and long-term impact of previous Olympics has frequently been overstated for host nations. However, after a difficult 2017, South Korea now has a key opportunity to use one of the world’s largest sporting event for a positive brand makeover that could produce a significant, lasting political, reputation and economic legacy for the country in the years to come.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.