Imagine the scene. It is the 13th century, and a merchant named Al Harith is on his way to Makkah for the Haj in a caravan of eager pilgrims and tireless camels — trumpets blow, flags wave.

He is halted in his tracks by a "roguish" character called Abu Zayed who accosts the travellers: "Do you comprehend what you are about to face and what you are undertaking so boldly?"

He attacks them for thinking the Haj was simply a matter of choosing the doughtiest camels and declaims: "No, by Allah, it is the sincerity of purpose ... and the purity of submission along with the fervour of devotion."

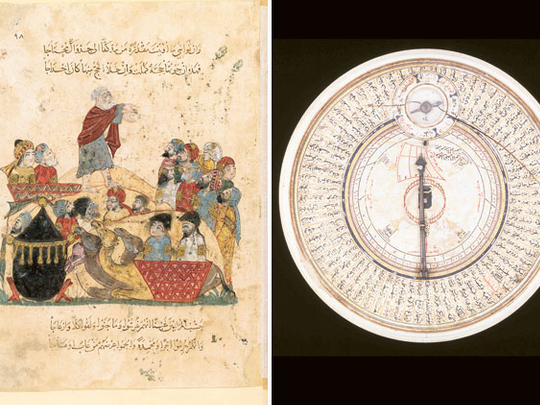

Luckily, we do not have to rely on imagination; the confrontation is described in a book, the Maqamat of Al Hariri, and is on display in exuberant detail in an exhibition at London's British Museum, Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam. The show captures the fervour of this remarkable avowal of faith while explaining its mysteries to a UK audience whose knowledge of pilgrimages barely extends beyond the Canterbury Tales of the Middle Ages.

Just as the travellers in the tales "long to seek the stranger strands/Of far-off saints ..." this exhibition is as much the story of the pilgrims as the rituals — a point made right from the start when the visitors walk towards the exhibition along a darkened passage lined with photographs of pilgrims. It is as if they are part of the throng heading for Makkah.

The exhibition highlights the traditional routes of pilgrimage which stretch from sub-Saharan Africa, from Cairo and Istanbul, from India and beyond and which took weeks, months and often more than a year to complete. One of the earliest accounts is by Ibn Jubayr, a Muslim from Spain, whose travels which started on February 3, 1183, are recorded on parchment. He complains of theft by Egyptian customs officers and greedy ship owners whose craft were so crowded that the pilgrims were like "chickens in a coop". He envied the rich who rode in shaded wooden litters "filled with soft mattresses", and grumbled: "As for the man who cannot afford these conveniences of travel he must bear the fatigues which are but the chastisement of God."

As a contributor to the show's catalogue points out, he sounds like the medieval equivalent of the traveller stuck in economy, envious of those in club class. A splendid illustration from the 19th century of two rather lugubrious camels supporting a sedan chair demonstrates that, then as now, the rich found the going easier.

The delight is in the detail. In the Crossing the Sea of Oman, a watercolour painting from the Pilgrim's Companion by Safi Ibn Vali (c 1677-80), there is advice on how to avoid sea sickness and fight off pirates. In Pilgrims Quarrelling on Hajj from the Kulliyat of Sa'adi Shiraz, 1566 — showing a comical bunch of travellers — there is a report of an exchange between the Hajjis: "If a pawn travels the length of the board, it becomes a queen and so becomes better; but these travellers to the Haj on foot have crossed the desert and become worse. You're no pilgrim! The camel's the real one."

The longest journeys were made by the pilgrims travelling to Jeddah by ship from India and the Far East. Thousands drowned, or were stricken by cholera due to the appalling conditions on board. In 1865, for example, out of 90,000 pilgrims, 15,000 died. No story is more shocking than that of the pilgrim ship, the Jeddah, which was abandoned by its officers in 1880 when they thought it was going to sink, leaving its 953 passengers to their fate. Amazingly, the ship and its human cargo were rescued and towed into Aden. The novelist Joseph Conrad turned the incident into his book, Lord Jim.

Soon after, with the shrewd commercial instincts that typified the British in 19th-century India, Thomas Cook, the travel agency, won a government contract to arrange package trips. The ticket they issued, with tear-off sections for each stage on the journey, is on display, as are examples of the minutiae of travel: compasses, such as one on wood from about AD1800, giving the direction to Makkah from 28 cities; wooden water-flasks from Mali, China and India; a milestone from AD700-800 reading "8 miles and this is two thirds of the road from Al Kufa" and a gravestone from AD900 for a pilgrim from Basra.

The exhibition is not merely about getting there (or not). The rituals that give the Haj such power are thoroughly explained with ancient paintings, textiles, tiles and artefacts, along with a satisfyingly grainy black-and-white film. Highlights include a spectacular mahmal — the tent carried by a camel which contains the Quran — from about 1867 in red silk, embroidered with silver and gold thread. There are 45 objects on loan from the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, including a representation of a bare-headed Alexander on pilgrimage from the mid-16th century and several elaborate textiles such as curtains for the internal door of the Ka'aba and from the tomb of the Prophet (PBUH) in Madinah.

Inevitably, the focus is on history and tradition, so it is surprising to find examples of contemporary art. Magnetism by Saudi Arabia's Ahmad Mater Al Ziad, has iron filings drawn to the black cube like so many massed pilgrims.

It is a magnetism that grows stronger every year. In 1932, 20,181 went on haj; more than 2.9 million went last year; and by 2014 the site will have undergone huge expansion — complete with helipads — to cope with two million pilgrims at a time. Who needs soft mattresses?

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.

Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam will run at the British Museum in London through April 15.