The people who really pulled the carpet from under our feet were the CIA," said Simon Mann, calm and well-spoken, as always. The former mercenary was talking to Weekend Review about his infamous escapade in 2004, when he and his cohorts tried to topple the dictatorship in Equatorial Guinea but ended up serving prison time in some of Africa's worst prisons. "When I am telling you this, I am very nervous, for sure. But I do have fairly good information from my sources that the CIA told the Angolan intelligence service to tell South African intelligence to stop the coup and have us arrested in Zimbabwe."

In a plot that would make the best thriller writer proud, Mann — backed by wealthy, right-wing businessmen in Britain and South Africa — planned to storm the wretched but oil-rich kleptocracy with about 69 other desperadoes under his command, topple President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo and replace him with the puppet, Severo Moto, to be flown from the Canary Islands, who would in turn grant Mann and his cronies lucrative oil deals and security contracts. The plot was almost totally lifted from the 1974 Frederick Forsyth thriller The Dogs of War.

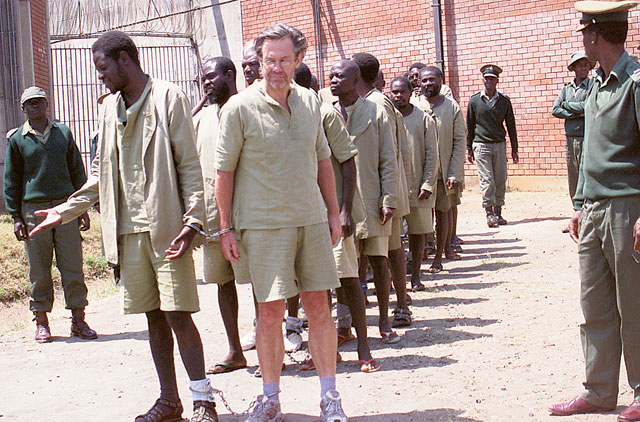

The coup was foiled even before it began, when Mann and his men were nabbed as their chartered aircraft made a stopover in Zimbabwe en route to Equatorial Guinea. Mann spent four harrowing years in Harare's Chikurubi Maximum Security Prison and almost two more years in Malabo's Black Beach Prison before being released in 2009 following a presidential pardon. He has now penned his own account of the debacle, titled Cry Havoc. While obviously written from the coup-plotter's perspective — and plagued by bad writing and basic errors (for instance, the map of Africa still shows the country we know as the Democratic Republic of Congo as "Zaire") — the book does provide some interesting insights into the minds of the mercenaries in the days leading up to the fiasco. It goes back and forth between his earlier adventures in Angola and Sierra Leone, and the Equatorial Guinea coup plot.

Mann, an Etonian who has served in the SAS and whose father has captained England in cricket, haunted the African continent for years. In 1993, his long-defunct mercenary firm Executive Outcomes — one of the first such "private military companies" — helped the corrupt Angolan government thrash rebels threatening to take control of the oil fields. As Mann admits in his book, he made millions from the venture.

His private army also helped the Sierra Leone government in the mid-1990s to regain control of the rich diamond fields, using helicopter gunships to cut down the crazed junkies of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) in Sierra Leone, who specialised in chopping off the limbs of thousands of innocent civilians. The mercenary adventure was loosely chronicled in the smash-hit film Blood Diamond. The RUF was backed by Liberian warlord-president Charles Taylor, who ended up facing war-crime charges in The Hague.

"What we did in Angola and Sierra Leone was very different from what we were trying to do in Equatorial Guinea," Mann recalled. "In Angola and Sierra Leone, we were supporting recognised governments and we were members of the military. I had been made a brigadier-general in the Angolan army! But what we were doing in Equatorial Guinea was completely outside the established arena."

I asked Mann how someone as experienced as him could possibly hope to get away with knocking off an entire republic in this day and age. "I did think that I could pull it off. I really did. Put simply, the fact that we had succeeded in Angola and Sierra Leone clouded my judgement. Because in those places we were very successful, partly because we had a mindset that if you kept going and were bold enough, it would work. Besides, I had the feeling that Spain [the former colonial power in Equatorial Guinea] and South Africa were backing the coup. There was no doubt in my mind about that. But I don't feel bitter about them as I didn't expect them to come and help. That is not how these things work," he said.

The plot was one of the worst-kept secrets. In the months leading up to the planned coup, just about anyone who mattered knew what was afoot. So why did Mann go ahead, knowing that the plans had been leaked? "I knew we were compromised. A lot of people knew what was going on. I actually couldn't see the red light. I had the Spanish government saying to me through intermediaries, ‘Go, don't wait, go!' And the South African government was saying the same thing. And they were in touch with the Spanish government. There was cross-communication going on," he said.

So who does Mann blame for the plot? "The only people I feel angry about are Ely Calil [a wealthy and reclusive Leban-ese-Nigerian businessman based in London], Mark Thatcher [the son of Margaret Thatcher, widely believed to have financially backed the coup] and a couple of others. They were not only backers but they were my brothers in arms. They were part of the operation. I feel bitter about them because once we were arrested, they ran away and did absolutely nothing — to not only help me but also the other men and their families. The legal fees, my wife Amanda — they did nothing. They did not even send a postcard! And that is betrayal."

Throughout his book, Mann refers to Calil as "The Boss", for legal reasons. "But in reality, for example, in the court in Equatorial Guinea during the trial, I made a lengthy legal statement at the request of the authorities and clearly named him. That's the truth. The United Kingdom libel laws are terrible. We cannot really name names. It's very difficult. I don't have enough money to fight another court case."

As for the CIA, he did not feel that they put paid to his plans to safeguard the interests of American oil firms in Equatorial Guinea. "It's more complicated than that. It is inconceivable that someone such as Ely Calil initiated this operation without having had the green light from the CIA in the beginning. So the next question is, if the CIA initiated this, why did they torpedo it?

"There are two possible answers. First, they set this up with the intention of torpedoing it. But I do not believe that. Second, as things began to go wrong, they got scared. They began to say: ‘Wait a minute, this guy Mann and the operation is a disaster. If this goes wrong, the blame may come to us.' And, quite sensibly, they thought they could stop this coup. I would do the same if I were them. They must have thought: ‘We can torpedo it, and go to Obiang and say we are your friends and protectors, and we've proven this. And we can only go on being your friends and protectors if you now follow the rules.' Contrary to what many people think, the CIA and the US oil firms are not comfortable dealing with a tyrant."

While Mann accepted that he made good money in Angola, he claimed he did not make any in Sierra Leone. And he said that the "horrible exercise" in Equatorial Guinea cost him £6 million (Dh34.2 million). But he was helped by many people financially to recover some of the cost.

In his authoritative account of the Equatorial Guinea plot titled The Wonga Coup: Simon Mann's Plot to Seize Oil Billions in Africa, Adam Roberts says that he believes the novelist Frederick Forsyth was himself involved in a plot to topple the then dictator of Equatorial Guinea, Macias Nguema, in 1973. Macias was the uncle Obiang had executed before taking over power in 1979. Forsyth wrote his famous book The Dogs of War in 1974, which, as documents released by the British National Archives appear to show, was based on real life. In 1978, The Sunday Times alleged that Forsyth had financed a real coup in Equatorial Guinea.

Interviewed by Roberts for his book in 2006, Forsyth admitted there was a "stillborn" attempt at a coup. Roberts writes in his book: "What is remarkable … is that the exploits were repeated precisely three decades later by another British figure, Simon Mann. But where the plotters of the real life first attack had a noble goal — removing a deranged dictator from power — Mann's scheme was organized for a more predictable reward. Where the old Equatorial Guinea was repressive and poor, the modern one is both repressive and rich — a far more appealing target for a hired gun."

I asked Mann if he really did use Forsyth's bestseller as a blueprint for his operation. "I did read it. It was going to be an adventure. It was a difficult mountain to climb. Angola and Sierra Leone — we kind of got pulled into it by circumstances. This [Equatorial Guinea] I didn't need to do. I had a beautiful house, a family and a lot of money in the bank. But then you get to the two big motives: Here's a terrible tyrant, people are being improperly arrested, tortured, and the place is a nightmare. And while ending a tyranny, we have the opportunity to make a lot of money. How could I say no?"

Incredibly, after his pardon, Mann has travelled to Equatorial Guinea three times and met with the despot, who invited him through the country's ambassador to Britain. "I thought it would be a nice thing to do … this guy whom I set out to overthrow has given me pardon, and I thought that is an amazing thing. The least I could do was thank him.

"We had a long meeting through a translator. We talked about a lot of things. He was a prisoner under his uncle. It helped that he could understand how it felt. We talked quite a bit about how he wishes to pursue justice against Calil and Thatcher. And he is doing so now in a case in Beirut. [There was an alleged meeting in Beirut of Calil, Moto and some other people involved in the plot.] They broke Lebanese law. And that is what the president is pursuing," Mann said.

There are plans to make Cry Havoc into a film, directed by Ridley Scott. Mann — who has played a minor role in the film Bloody Sunday — said he wouldn't be playing one in the proposed film. "If nothing else, Bloody Sunday taught me that I am not an actor," he said.

Now, in semi-retirement, Mann feels that he was a very small pawn in a very big game. "That's the world we live in. I am very happy to be a pawn. I was a soldier in the British army for 12 years. And you can't be a bigger pawn than that."