His father walked out on his mother and him when he was six years old. Expected to be the "man" of the family from a young age, Sean Jones, now 31, encountered early on the hardships that abandonment brings. But it is this, combined with the strength of purpose that he drew from his single mother, that perhaps drove him to give up a well-paying job as a computer analyst at Xerox in Texas and move to Rwanda to take over the running of an all-boys orphanage. What started as a six-month stint for Jones has now completed nearly two years, and from relying on his savings — for more than a year — to earning a salary of $300 (Dh1,101) a month, he has come a long way. Weekend Review learns about the force that binds him to Kigali, the Rwandan capital. Excerpts:

Is there any particular reason behind why you chose Rwanda?

In 2009, this urge to make a difference grew stronger in me. Xerox agreed to give me six months off to do some volunteering overseas. I was looking for organisations that would let me teach English. But I found that most NGOs were the pay-to-volunteer kind; but I wanted something more substantial, something that would allow greater involvement with a community. After a concerted search, I found this small organisation called the Rwanda Orphanage Project — Centre for Street Children (ROP) that had been set up by a group of friends in San Diego, California. On a visit to the country several years ago, they were told about this orphanage and its appalling conditions. They went back to the United States and raised money to create a fund to support the children there, but without any volunteers on the ground, they did not have direct control over the orphanage.

I met them in California and told them that I would like to volunteer. They were happy with my proposition and eager to have me start right away. In January last year I arrived in Rwanda with one of the organisation's members. He showed me the ropes for two weeks, and from then on I was on my own.

Were there any challenges you faced while working with the orphanage?

The orphanage was an abandoned warehouse in an industrial part of town by the river where street children would congregate at night for shelter. A Rwandan church offered to help by donating food and clothes. The person put in charge of the orphanage, however, turned out to be corrupt and was replaced by another supervisor. When I came in, the orphanage had some 200 children between the ages of 6 and 20. The place was run-down, with a leaky roof, one light bulb and no running water, furniture or facilities. It didn't take too long to find out that the people running the orphanage there were actually pocketing the money sent by the donors in the US. I made my case to the board of directors in California and they put me in charge of the organisation. So here I was, in my first month in a foreign country, a volunteer for an orphanage being asked to run the place instead.

It was a new place and you didn't even know the local language. Was it difficult to put things back on track?

The first thing I did was fire the supervisor and the members of staff who were hand-in-glove with him. He was a sociopath, abusing the children physically and mentally. And these poor children would rather be subject to that abuse than live on the streets without food. On top of that, this supervisor claimed to be the founder of the orphanage, and since he knew the right people in the government, went about maligning my reputation.

In a system as bureaucratic as Rwanda's, it was difficult to make a convincing case out of the testimonies of the children and the remaining staff. But we somehow managed to get him out despite his threats. But things didn't end there. Almost as if to defy my place in the organisation, this man just used to walk into the office at will. We met the local leaders, including the mayor of our district and the minister of General Family Promotion who is in charge of all orphanages in the country, and after endless persistence, the government intervened and told the supervisor to stop bothering us.

What did the future look like at that point?

Bleak! One day the government visited us and said that the place wasn't good enough for children. We were given a month to move out and an ultimatum that if we didn't, the orphanage would be shut down. This was in March last year, three months into my arrival in Rwanda. We didn't have the money to buy land or move into a new building. The new director of the orphanage and I began rushing around Rwanda looking for an abandoned building or something that could function as a temporary shelter. Divine intervention came in the form of a wealthy Rwandan man who offered his school that had been abandoned for a number of years — and he let us use the premises for free! This was a miracle. So, while earlier we were in a shoddy industrial warehouse, now we were in a cleaner and quieter area called Kanombe, on the outskirts of Kigali. We moved here in April 2010. Today we have our own land.

How do you know which child needs to be taken in?

Not all street children are orphans; some of them beg because they can make more money for their working parents. Generally, we see very, very unkempt children washing in the sewers, begging for food, and we try speaking to them. I don't usually do the talking, because apart from the language problem, their first reaction on seeing a white-skinned person is to claim to be orphans in the hope of getting something out of him. So we have the Rwandan staff talk to them and make sure they are not just pretending. We bring in children between the ages of 5 and 10. Many come with behavioural problems or drug and alcohol addictions. We have 5-year-olds who sniff glue or smoke cigarettes. We counsel them, but sometimes they just sneak out and find a bottle of alcohol themselves. Then we again have to bring them back and tell them why it is bad for them. But with the older ones, we need to be more strict.

What facilities do you provide at the orphanage?

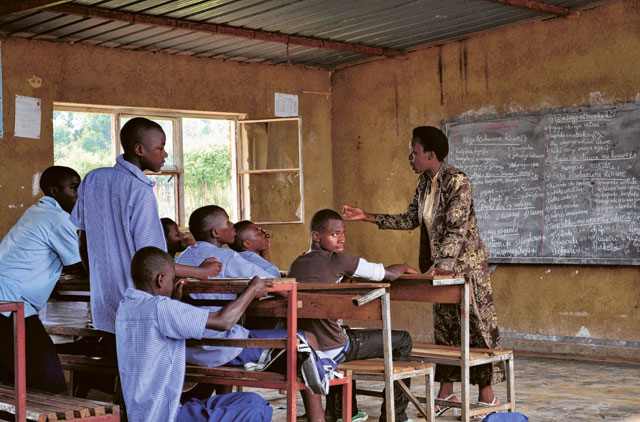

Apart from food and shelter, we have a primary school from Level 1 to 6. We provide education to the boys we house at the centre and support children from poor families in the neighbourhood. We also pay for their secondary education once they complete their term. At present we fund about 35 to 40 children, which costs about $100 a child per term. Last year six of our students graduated from secondary school, three of whom were granted university scholarships. Children who start school late or fall back academically are also offered vocational training. Jenny Clover, a journalist from London who has taken time off from her job, supports me at the orphanage and has started an art programme and created a playroom and a library. Last year I was able to scrape together enough money to form a football club so the boys would have some activity. The children now have football shoes and uniforms and even play other schools.

Do the children ever face discrimination when they interact with others in society?

Yes, and primarily from peers. The other children tend to say: "Watch out, these are street children. They will take your wallet." Or in the church, people say, "We don't want street children here." But there have also been times when people have said that our boys are far more well-behaved and respectful than other schoolchildren. I tell them to be proud of such remarks rather than be bogged down by rejections.

Are you focusing on anything in particular now?

Orphanages have a hard time finding donors, because they are known to be corrupt — we used to be an example of that. So it is hard trying to convince others that we are not going to be corrupt or wasteful with the money. ROP has no corporate or foundational support and relies on the charity of citizens. We spend $7,000 a month to provide for the 100 children we look after. Food alone comes to $2,000 a month. We have started a programme where a child can be sponsored for $35 or $50 a month, but we would love to have each child sponsored by two donors. Earlier this year, we had a Norwegian donor who helped build a contemporary kitchen here for $6,000. But our overall financial situation is a little shaky and we are desperately seeking help to keep our mission alive.

You said that you now have your own land. How did you manage that when ROP is in dire need of funds?

We had an Australian group visit us this summer. Not too long after their visit, one of the members of the group, Tony, contacted Jenny and informed her that he and his wife Carol wished to help ROP buy its own land. We were pleasantly shocked at the offer and told him we already had a plot in mind. This land was being sold by a local family at a very low price, considering its size and location. Tony asked us about the price and within days had made a donation that covered the full cost. The land sits on a gently sloping hillside, with a road at the top and a river at the bottom. The river will help us build greenhouses that will allow us to grow crops year-round to sell at the market. This could, in fact, be ROP's first income-generating project.

Has any international organisation expressed interest in ROP?

In August we signed a partnership with JC Dragon's Heart Europe, which is the European branch of Jackie Chan's original Chinese foundation. Their first donation to ROP will be for a water tank to ensure we do not run out of water during Rwanda's dry seasons. We are looking to build a long-term partnership with the organisation.

Do you still have your job at Xerox?

When the initial six months were over, I managed to get an extension from Xerox for another six months. But my request for another year of unpaid leave was turned down. I don't know what my status is in the company now. But as much as I used to love my work there, I have no intention of going back. In 2010 I was invited to join the ROP board of directors. I find this project so much more rewarding — you go from helping someone's stock prices rise to actually making a difference in children's lives. There is no comparison between the two.

For further information on the Rwanda Orphanage Project, visit www.rwandanorphansproject.org

Vasanti Sundaram is a writer based in Dubai.