New York: In the 21st century, parenthood and paranoia often walk hand in hand.

For some, the blessed event is followed by high-tech surveillance, a monitoring system that tracks the baby's breathing rhythms and relays infrared images from the nursery. The next investment might be a nanny cam, to keep watch on the child's hired caregivers. Toddlers and grade schoolers can be equipped with GPS devices enabling a parent to know their location should something go awry.

To cope with the uncertainties of the teen years, some parents acquire spyware to monitor their children's online and cell phone activity. Others resort to home drug-testing kits.

Added together, there's a diverse, multibillion-dollar industry seeking to capitalise on parents' worst fears about their children, fears aggravated by occasional high-profile abductions and the dangers lurking in cyberspace. One mistake can put a child at risk or go viral online, quickly ruining a reputation.

New tools

"There's a new set of challenges for parents, and all sorts of new tools that can help them do their job," said David Walsh, a child psychologist in Minneapolis.

"On the other hand, we have very powerful industries that create these products and want to sell as many as possible, so they try to convince parents they need them."

Some parents need little convincing.

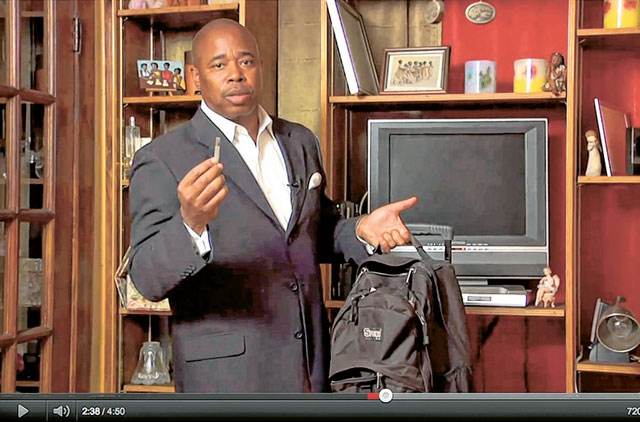

In New York City, a policeman-turned-politician recorded a video earlier this year offering tips to parents about how to search their children's bedrooms and possessions for drugs and weapons. In the video, State Senator Eric Adams, who has a teenage son, insists that children have no constitutional right to privacy at home and shows how contraband could be hidden in backpacks, jewellery boxes, even under a doll's dress.

"You have a duty and obligation to protect the members of your household," he says.

Another parent who preaches proactive vigilance is Mary Kozakiewicz of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, whose daughter, Alicia, was abducted as a 13-year-old in 2002 by a man she met online. He chained, beat and raped her before she was rescued four days later.

In recent years, both mother and daughter have campaigned to raise awareness of internet-related dangers.

Mary Kozakiewicz urges parents to monitor children's computer and cell phone use, and says those who balk out of respect for privacy are being naive.

"It's not about privacy — it's about keeping them safe," she said.

- Baby monitors:

These devices, some limited to audio monitoring, others also with video capability, have developed a reputation as a mixed blessing. They can provide parents with peace of mind, freeing them to be elsewhere in the house while the baby naps, but sometimes they accentuate anxiety.

"Some parents are reassured by hearing and seeing every whimper and movement. Others find such close surveillance to be nerve-racking," says Consumer Reports, which has tested many of the monitors.

- Tracking devices:

Of the roughly 800,000 children reported missing in the US each year, the vast majority are runaways or were abducted by a parent. But there are enough kidnappings by strangers, including a few each year that make national news, to fuel a large, evolving market for products catering to apprehensive parents.

The devices range from clip-on alarms to GPS locators that can be put in a backpack or stuffed in a doll, but they have limited range and can raise safety concerns of their own. Ernie Allen, president of the National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children, says the devices can be helpful in some circumstances but worries about overreliance on them.

- Spyware:

For many parents, one of the toughest decisions is whether to spy on a child's computer and cell phone activity. It is common for some children to send more than 100 text messages a day, and a recent Associated Press-MTV poll found that about one-quarter of teens had shared sexually explicit photos, videos and chat by cell phone or online.

Walsh, the Minneapolis psychologist, says the best initial step for parents concerned about online risks is a heart-to-heart talk with the child. "If it does make sense to use some spyware, I would never do that in a secret way," said Walsh, whose own three children are now adults. "Tell your children you'll check on them from time to time. Just that knowledge can be effective."

Mary Kozakiewicz, a Pittsburgh mother disagrees, saying use of spyware must be kept secret.

- Home drug tests:

Compared to tracking and spyware gadgets, home drug testing kits are relatively low-tech and inexpensive. But they raise tricky issues for parents, who may be torn between alienating their child on the one hand and living with unresolved doubts about possible drug abuse on the other.

David Walsh directed an adolescent treatment programme earlier in his career and says the at-home tests can be appropriate when parents have solid reason for suspicion.

A look at some of the monitoring tactics and products available to parents: