Driving from Chakrata to Sawra, a tiny hamlet tucked behind a hill in Uttarakhand, a state in northern India, is a thrilling yet chilling experience. The puckered-up mountains, with patches of green here and there, look quite enticing. There are primates hopping on the branches of tall deodar and cheer trees, oblivious to the steep heights or precarious cliffs.

The cool breeze seeping through the engine of the car makes your toes go numb. The rickety road with mounds of landslide rubble rustled up on its left and a few open drains flowing across (signs of habitation on hills above by) from left to right makes for a dangerous climb.

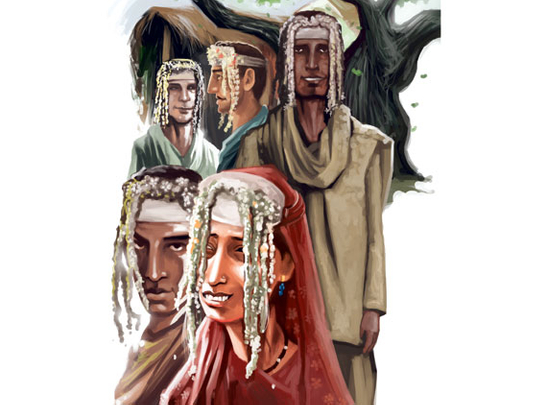

You are in Jaunsar-Bawar, the tribal valley that is famous or infamous — depending on whether you are for or against puritans — for its tradition of polyandry and polygamy. The valley is split in two with Bawar, the snow-clad upper region and Jaunsar, its lower half, together housing over 400 villages. Though the residents of the two regions speak different dialects — Jaunsari and Bawar bhasha (a Hindi variant) — and wear different attire, they claim to be descended from same forefathers — the Pandavas, heroes of the Mahabharata epic — and follow an analogous culture. And both practice polyandry and polygamy with families of multiple husbands and multiple wives coexisting in harmony.

"There are at least 50-60 polyandrous and polygamous families in Jaunsar-Bawar. In Monti village, four brothers have one wife. In Sidi, Soopa had three wives. His son has [outdone] him and married four times. It's another matter that two of his wives died and the third split from him," said Moham Singh (name changed at his request), our local guide for the Jaunsar-Bawar tour.

The Jaunsaris have strong reasons for following polyandry and polygamy. While they attribute polyandry to the Pandava brothers — Yudhishthir, Bheema, Arjuna, Nakul and Sahadev — their devtas (deities) who shared Draupadi amongst themselves, for polyandry, they say more wives mean more hands to do domestic chores, farming and cattle rearing.

More often than not, it's the people from affluent castes and those with large landholdings who practice polygamy. Bhagat Singh, a farmer in Pokhri village, for instance, has three wives.

While one of them looks after the house, another takes the cattle out for grazing. The third is responsible for the upkeep of the farms.

Another interesting feature of polyandry is that though the brothers share one wife, the children sired by them only carry the name of the eldest brother.

"For all practical purposes — except sex — the wife belongs to him. He marries her. The children born of such arrangement write his name for a father," Singh, who hails from Sidi Barkoti, a village in Jaunsar, said.

Easy divorce proceedings

Unlike the so-called civilised world in India where it takes years and, at times, a lifetime in courts to get out of a failed marriage, in Jaunsar it is much easier to attain a divorce and remarry.

"It's known as Chhoot or Kheet [abandon] in local parlance. The only thing is in such cases, either the wife's family or her prospective lover will have to pay compensation to the husband," said Arvind, a worker with a non-government organisation (NGO) who has worked with the Jaunsars.

During Magh Mela, the biggest festival of Jaunsars, the festivities continue for a month beginning with the sacrifice of a goat in the second week of January. During this time, the tribals drink Pukhai (a kind of locally brewed beverage); indulge in songs and dances) and pray to Mahasu devta, a powerful deity who they believe is another form of Shiva, one of the three main gods in the Hindu pantheon. All Jaunsars settled outside return to their homeland to celebrate this festival.

The Jaunsars basically live on agriculture, animal husbandry and bee keeping. Unfortunately for them, agriculture is largely dependent on rain and natural sources of water. Their buffaloes are quite adept in negotiating the heights.

They tend bees in the warmer parts — generally the ground floor — of the house and collect honey for personal consumption and sale. The tribe has no access to medical facilities with hospitals only located in Chakrata, the hilly town, which is several hours drive. They make do with herbs they collect.

It is widely believed that King Virat, an accomplice of Pandavas ruled Jaunsar-Bawar, then known as Varnawat, during the Mahabharata period. Virat's daughter Uttara was married to Abhimanyu, the son of Arjuna.

The region still has the ruins of Lakshagriha, the incendiary palace Duryodhana built to burn his cousins the Pandavas alive. The Pandavas, who were in disguise, were believed to have escaped unhurt to Chakrawati town, the present-day Chakrata.

They were said to have spent considerable time in Viratnagar, the ruins of which are supposed to be scattered on a ridge known as Chorani Dhar or Birat Khai. The Pandava brothers were supposed to have ruled over parts of north India from Hastinapur, a town in Western Uttar Pradesh, several thousand years ago.

Bonded to slavery, superstition

Since Jaunsaris have lived on the inhospitable, inaccessible terrain, isolated from the world for several centuries, they are steeped in poverty, illiteracy and backwardness. With these come superstitions, child marriages and bonded labour. You come across several Jaunsaris who claimed to have been visited by the spirit of the Pandavas. "When we sing and dance next to the Pandava chaura [a platform near which they congregate for celebrations during festivals], the Pandava's atma [soul] visits the purest of us. He brandishes the mace the way Pandavas would have done in their time," says Jeema Ram, an elderly farmer in Sawra village.

Though the central government abolished bonded labour in the country long ago, enacted the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act in 1976 and the Uttarakhand government records no bonded labourer in its documents, the system continues unabated in Jaunsar. Moham Singh claims there are still at least a few hundred bonded labourers in the region. "These people [generally from lower castes like Kolta, Dom and Bajgi] borrow money from upper caste landlords and then toil in their farms for life. The irony is they are never able to pay the principal amount as their lifetime bondage is calculated in exchange for interest," he says. Singh discloses that during visits by State or central government officials, the bonded labourers are threatened to be silent. There are also instances when a man surrenders his wife to the landlord for the money borrowed by him. The landlord then makes money by forcing the woman into prostitution.

Tree's bark for liquid detergent

The flora and fauna is a source of multiple uses for the tribals in Jaunsar. Not only does it offer them cure from minor ailments, but also provide them raw material for their beds, is cooked for vegetables and used as a fodder.

Bichhu grass (thorny grass that draws its name from a scorpion), for instance, is used for knitting ropes as well as preparing vegetables and chutney (an Indian sauce). Similarly, the bark of the Vimal tree, when crushed, produces a sticky substance which Jaunsaris use as liquid detergent for washing clothes. Since the tree's wood burns slowly and for long hours, its branches often function as a torch for the Jaunsaris. The dry leaves of the tree are spread under cattle and goats to provide warmth. The same leaves are mixed with dung to prepare fertiliser for their farms.

Mehar Singh, a tribal, said that Jaunsaris largely sustained on nature for their daily needs and only travel to the city to buy salt and sugar.