The saying that helping others creates an enormous inner joy could not be truer than in the case of Steve Sosebee, the former American journalist who switched careers and established an organisation to help sick and needy Palestinian children in the middle of the first Palestinian intifada nearly 20 years ago.

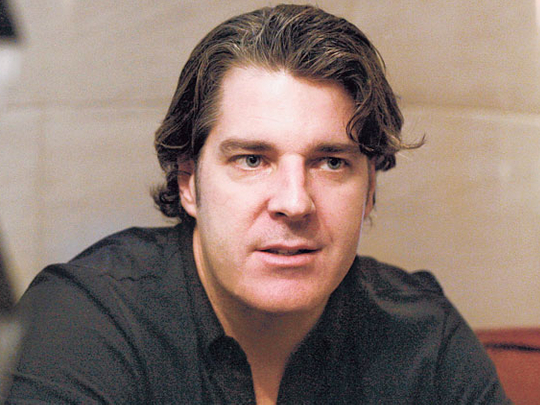

Sosebee, who combines strong will, humanity, the passion to help others and relieve their agony, and a sense of sacrifice, believes he is carrying out his "responsibility in life as a human being".

His conviction grew with the passage of time, he says, helping him overcome the grief of losing his Palestinian wife after 17 years of marriage. She lost her battle against cancer last year, leaving their two daughters with their 45-year-old father.

Being involved in humanitarian work, soft-spoken Sosebee is fulfilling his "desire to live a life of purpose", regardless of what kind of house or car he has, or what type of clothes he wears.

"I knew even when I was very young that I wanted to live a life like this. I wanted to look back one day and say when I am older — inshallah I will be an old man — [that] I made a difference in [others'] life. That I didn't live just for personal pleasure or to accumulate wealth or something like that," he says.

"I wanted to make a difference and I wanted to do it in a way which would help people who are suffering injustice," Sosebee told Weekend Review in an interview during a recent visit to Dubai.

Sosebee's wish has come true. Today he is playing an instrumental role in improving the lives of hundreds of Palestinian children.

Sosebee's story began in the late eighties when he was a journalist with The Washington Report and Middle Eastern Affairs from the West Bank and Gaza Strip. The young American reporter saw "a lot of injured children" during the first Palestinian intifada (1978 to 1993).

"As an American, I felt guilty about what was going on there because of the policies of my government," he says, referring to what most Arabs describe as Washington's biased policies towards Israel.

"So I wanted to do something to show the people that not everybody agreed with this policy, and to do it in a positive and humanitarian way," he says.

But because options to show support to Palestinians were "limited" due to the political situation, Sosebee mulled the "most effective" way to support them.

"So when I saw injured children and those in need of medical care, I started to place them in American hospitals for free treatment. Then I realised that was a useful way to contribute to people: providing the medical care they needed."

The project grew within a few years and the Palestinian Children Relief Fund (PCRF) was established in 1991. During Sosebee's work, he met Huda Al Masri, a Palestinian woman who was born in the Al Amari refugee camp near Bethlehem.

She was volunteering as a social worker in Occupied East Jerusalem. They fell in love and got married. Al Masri worked with him "side by side" to establish PCRF and helped him fulfil his mission.

"Despite that tragedy [of losing his wife] in my life, I am still dedicated to this work. It is a life mission," he says. "I still feel young. I am at the peak of my physical and mental ability to do this work. So I have to grab this opportunity, apply all my energy and all my efforts to make this organisation and this work effective and possible."

Since its establishment, PCRF has sent nearly 1,000 Palestinian children for medical treatment to different parts of the world — mainly the United States, and cities including Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Italy. Furthermore, 10,000 Palestinian children from the West Bank, Gaza Strip and refugee camps in Lebanon and Syria have been treated by volunteer doctors who travelled to the West Bank, Gaza and other cities in the region to operate on children — including open-heart surgery, orthopaedic surgery, and plastic and reconstructive surgery. The process starts with a PCRF team of field workers and social workers finding children who are in need. In some cases, the sick children's families search for the PCRF. Then a team of doctors evaluates the cases and decides if the children can be treated in the Occupied Territories or if it would be better for them to be sent abroad.

One of the factors taken into account is the age of the child who will be sent abroad alone. The preferable age is under 15, because those children sent abroad spend the recreation period with host families, "where there are mothers and sisters".

Children over 15 are "not boys any more, so sometimes it is a social issue" — yet there are exceptions. Khalil, a 17-year-old Palestinian man, was sent to Dubai for treatment after he lost both legs in an Israeli raid on Gaza a few years ago. Surprisingly, he became a good diver afterwards.

Once the name of the child is added to the list of children that need to travel abroad for treatment, Sosebee's mission starts: to find a place to send the child.

With the internet, it has become "very easy" to find people all over the world who can help. "So I have no excuse to not be able to help a child in need of treatment. It just takes time in front of the computer to find and to communicate and to connect, to have good information and to have good follow-ups. So I know how it is done. It is not so much about contacts, it is the method of finding this type of treatment. So sometimes I already have contacts in certain areas, where I can go back and ask for help, and sometimes, I have to start afresh and look for a new doctor; someone I have never met," he says.

Correspondence processes take several months. In some cases, Sosebee doesn't send more than one request for each child. "Sometimes, I wait for two months and the answer is ‘no'. Since I have not asked anyone else, I have to start all over again.

"In some scenarios, two months have been wasted while waiting for a positive answer. Sometimes it is very difficult to arrange things quickly because of the way it functions. You can't push people who are going to give you free treatment to act quickly. Basically, you are asking them and they have to give you an answer based on their schedule."

Today PCRF prides itself on being the "main non-profit NGO that is providing free medical care for sick and injured Arab children in the Middle East that is not available to them in their homeland", according to its website.

And now when its founder looks back, he still recalls the cases of Palestinian children that he feels he could not help because his hands were tied owing to the limited availability of medical options some 20 years ago.

The cases that are still alive in his memories are not success stories but rather those where he wished he could have done more to help. "We had children who are paralysed, who couldn't walk. The surgery provided was just to make it easier for them to sit in a wheelchair, not to make them walk again. Those cases I remember very well, because you want to do more but sometimes when medicine isn't there, there isn't more you can do."

Many people in the world feel very strongly about helping children get medical treatment, Sosebee said. Such a fact helped PCRF bring doctors to the Occupied Territories to operate on children in need. They come from many countries, including the US, France, Germany, New Zealand, Australia, Italy, Britain and Spain.

"This is a sign for everybody, that there is a strong level of support and solidarity from outside, where people care about Palestine, and they care about the children there," he says.

"We just cover the expenses for the children to fly out and for the volunteering doctors to come in. We now have three teams in the West Bank: plastic surgeons, neurosurgeons and maxillofacial surgeon teams from America. All of them are volunteers. We just cover flight fares, their hotel bills, expenses for conveyance and food, very basic things," Sosebee says.

While the US is "by far" the top country in terms of receiving sick Palestinian children, Sosebee explains that individuals and institutions also deal with his organisation. Nearly 700 Palestinian children have been treated in the US since 1990.

"There are lots of Americans who believe in this work and there are many who are not connected to the region ethnically — they are not Arabs. There are even Jewish doctors," he says.

Americans who support Palestinians and their cause face difficulties, mainly for political reasons, he points out.

"The name Palestine and the issue of the Middle East scares some big institutions, [in the US] because the right wing supports Israel. It accuses anybody helping Palestinians as being anti-Semitic, which is a cowardly argument to make when you have nothing else to fight with; you start to make accusations that have no foundation, but this is what they do. For some doctors it is not worth facing such abuse and they can go to other places, or other areas, to fulfil their humanitarian obligations," Sosebee says.

"At the same time, people know that this is not anti-Semitic to help a child and, in fact, it is the basic humanitarian principles that the Jewish religion, Christianity, Islam, Hindu, [and] all the main religions are based on. Even if you are an atheist, it doesn't matter. So nobody can say we are against anyone. We are for something, not against — we are for freedom, we are for children getting treatment, we are for healing, we are for spreading passion and love.

"We are against hatred and we are against war and against violence and against poverty and against injustice and against occupation, but we are fighting it through love and healing and support for those people."

Some Palestinian children were treated in Israeli hospitals but "not many" through PCRF. This is not due to political reasons but because of the Israeli health-care system. Israeli hospitals are designed to provide services for Israeli citizens but not foreigners who can't pay for treatment.

"Usually, they don't make exceptions for those cases. I don't know of any cases that went to Israel without some sort of funding from some party. So there are programmes in Israel where some parties are paying, American organisations are paying, but in the end somebody is paying, or the Palestinian ministry of health or the families of the children are paying. We don't have the money for this. Our job is to find treatment for children anywhere and benefit from that care for free."

While Sosebee stresses he doesn't allow his personal political feelings to interfere with his professional responsibility and humanitarian obligations, he says the Israelis "don't make specific problems for him too much".

He is a citizen of a country that is being considered a staunch supporter of Israel and the superpower that is allied with Israel. He is also involved in humanitarian, not political, work. Yet there are problems created by political and security reasons. "We are working in an occupied area where there are checkpoints and restrictions on travel; we are working in Gaza, which is under siege, and getting in and getting out is extremely difficult. We have teams in the West Bank but getting children outside Gaza to go and get treated is extremely difficult. But the obstacles we face are the normal obstacles that exist under occupation, that every Palestinian has to suffer," he says.

Sometimes, getting visas for sick children is another obstacle, he says. Some countries don't issue visas for Palestinians from the Gaza Strip or the West Bank.

Today Sosebee opted to continue living in the Occupied Territories for many reasons, including personal and professional ones, despite the legal difficulties.

"My problem in Palestine is a visa issue; I only have a tourist visa. My daughters [Dema, 14, and Janna, 4] are Palestinians and have Palestinian passports, but I don't. And I am not able to live there, I don't have residency permit and I have to travel [frequently]. I find it much more rewarding to do my work on the ground in Palestine. I love that country; I love the work I am doing there. It is difficult sometimes; I have my family and lots of friends in the US whom I miss. You know, I am an American, after all, I love baseball and things like that, I miss that. But these are minor things. These are not important when you are able to change someone's life or build a cancer hospital and save the lives of children," Sosebee says.

"I am raising my children with the same identity, as Palestinian and American girls who have both identities, both cultures, both languages, and so they have to live there and have that chance to learn the [Arabic] language and be close to their relatives."

Sosebee's work by itself is a reason to continue living, while helping others and saving lives is a source of happiness in life.

Seeing limbless children who are showing sufficient strength in their attempts to live a basic life or eat or drink like normal children is by itself a source of strength.

"Whenever we complain, we have to remember people are suffering in much worse situations. It is easy to forget and to think about your own situation and complain or feel angry or feel frustrated even when a minor issue affects you in a negative way — maybe your telephone is not working, or maybe the internet, whatever, something stupid, you become angry, and upset when it is really not important," he says.

Sosebee's next project is to establish a paediatric cancer centre in the West bank city of Bethlehem. Its aim will be to serve children "who have cancer and cannot get good treatment".

From the UAE to Palestine with love

By receiving scores of sick Palestinian children for free medical treatment, the UAE comes second in the list of countries that offer such treatment.

Several institutions in Dubai, Sharjah and Abu Dhabi are offering financial aid to the Palestinian Children's Relief Fund (PCRF), said Steve Sosebee, chief executive officer and founder of PCRF. Sosebee toured several cities in the Gulf recently, hoping to increase the number of children being sent to the region to receive free medical treatment.

While the Mohammad Bin Rashid Al Maktoum Charity Foundation helped bring children to Dubai for free treatment, His Highness Dr Shaikh Sultan Bin Mohammad Al Qasimi, Supreme Council Member and Ruler of Sharjah, helped through his financial assistance to build a paediatric surgery department in Occupied East Jerusalem for children.

His wife, Shaikha Jawaher Bint Mohammad Al Qasimi, chairperson of the higher council for family in Sharjah, is also among the prominent financial helpers. In 2008, she launched ‘Salam Ya Sigar' campaign (which means "both peace and greetings, you little ones").

"It [the campaign] enabled us to operate on children in Palestine, particularly in 2009, when they supported a lot of cardio-celiac teams and a lot of surgery teams who came to operate. It was through their support that most of these teams came and treated thousands of children," Sosebee said.

PCRF is one of the Palestinian-based humanitarian organisations that benefited from the aid provided by the Salam Ya Sigar campaign in the past three years and Sosebee praised the role of the campaign in the Palestinian colonies.

At the same time, Abu Dhabi's Shaikh Khalifa medical centre is treating two Palestinian children with orthopaedic problems.

So far, 53 Palestinian children have been treated in the UAE in the past four years. After the UAE, Italy is in third place on the list. Recently, an Italian doctor volunteered to operate on a little girl from Gaza with heart problems.

Helping PCRF through financing some of its projects, or through accepting its requests to treat children for free, Sosebee says, is coming because results are clearly seen in a relatively short period of time and they really make a difference quickly, unlike other campaigns.

"We have children who are sick or injured and need to be operated on. They see that we bring teams to work and operate. So it is very easy to see the results in comparison, for example, if you want to see a campaign to combat smoking or to educate people about the dangers of tobacco.

"You don't see results quickly, it takes a long time, though it is important and should be supported. It is not easy to judge how effective such a campaign would be," he said.

"But for us, it is easy to see, because you have a list of children who need surgery. The PCRF operates on them and they are off the list. They are cured. They are better. Or maybe they are children with burns from fire or heart problems or children with other types of injuries or needs. You have them clearly identified. You operate on them and they are cured."