Yorkie bars, Nestlé has always told us, are "not for girls". They are to be growled from their wrappers and chewed in mouth-sized chunks by manly men, men with stubble, men with muscles that bulge like bellies. Flakes, however, are for ladies. Pretty ones, in lipstick and baths, who crumble off a feminine bite, before letting their eyes fall closed in pleasure.

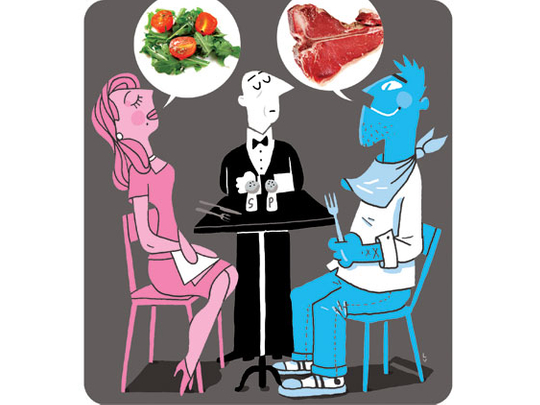

It's a complicated business, eating. And one made knottier by the idea that some foods are masculine (burgers, steaks), while others (yoghurt, quiche) are strictly for girls. Were these ideas of gendered eating originally generated just for ad campaigns or could the clichés point towards a deeper truth? Do men and women need different diets? How many of our views on what constitutes "women's food" come from how we're brought up and how many are tied to something genetic? If men are from meat, are women from cupcake?

Gastronomer's take

Grant Achatz, molecular gastronomist and winner of the James Beard Foundation's award for best chef in the US in 2008, snorts at the idea of gendered eating. He says: "What is a masculine presentation? Is it a giant chunk of roasted meat? What makes that manly — the caveman connotation?"

When Yorkie relaunched in 2002, Nestlé's marketing director explained its decision to increase the drive towards men. According to Andrew Harrison: "Most men these days feel as if the world is changing around them and it has become less politically correct to have anything that is only for males. It used to be that people recognised that men needed places to be, in a simple sense, men. Yorkie feels this is an important element of men's happiness and is starting the reclaiming process of making a chocolate just for men."

Because, of course, chocolate has traditionally been thought of as primarily for children, but secretly for women.

Psychologists say chocolate's appeal to women is in its status as a forbidden pleasure to those on diets. The chocolate industry is dominated by brands aimed at women. Jill McCall, brand manager at Cadbury, is careful to point out the difference between the indulgent, feminine bars (Flake, Galaxy) and the masculine "hunger bars" (Boost, Snickers) — which are nut-filled and huge, rather than providing a girlish "treat" — thereby creating markets within markets. Recently Mars launched the Twix Fino, with a third fewer calories than the old-fashioned Twix.

Bep Sandhu, from Mars, told trade magazine The Grocer: "The lighter version will help expand the appeal of the brand to female professionals looking for a lighter snack." Along with the new Galaxy Bubbles, it appears that yet another market of chocolate for women is blossoming the diet bar. "The role of marketers is to understand motivations, needs and desires, so we're always mindful of consumers' changing needs," says Elizabeth Davies, communications manager at Nestlé, where they're responsible for marketing Kit Kat Chunky (manly) and Kit Kat Senses (lady-like). "If there is an obvious gender split and the incremental business opportunity can be justified without jeopardising the core brand, then brands will continue to seize the initiative."

Chocolate is one of the things most associated with a female diet but it's when we think about savoury foods that we're able to separate the advertising from the eating.

The role of evolution

David Katz, director of the Yale-Griffin Prevention Research centre, believes our gendered diet can be explained by evolution. As cavemen, he suggests, men were hunters, relying on protein to build muscles and seeing meat as a reward, while women were gatherers of fruit and vegetables.

"Men and women have differences in physiology, which might have to do with early access to different kinds of food," he says. Differing access to foods in prehistoric times, he says, led to gendered patterns of eating today.

Yvonne Bishop-Weston is a Harley Street nutritionist who agrees that men are drawn to fats, meats and proteins but says it's not down to an "evolutionary need — it's down to socialisation. Boys are encouraged to have big appetites from a very young age. It appears possible that there are fat receptors in the brain, so everybody craves it, and because of our greater hormone cascade, women actually crave it more."

Bishop-Weston sees gender differences less in how people eat, more in how they think about their diets.

"Women have more emotional attachments to food — due to media pressure they attach guilt to carbs and saturated fats, and often feel a responsibility to eat healthily in a way men don't," she says.

"Interestingly, though, I see a trend towards ‘effort' that spans and unites the sexes. People are becoming more receptive to things that take longer. People are looking for an identity with their food. As everybody's lives are getting more stressful, we feel worse and we need more nutrients. So men and women are getting scared into eating well," she adds.