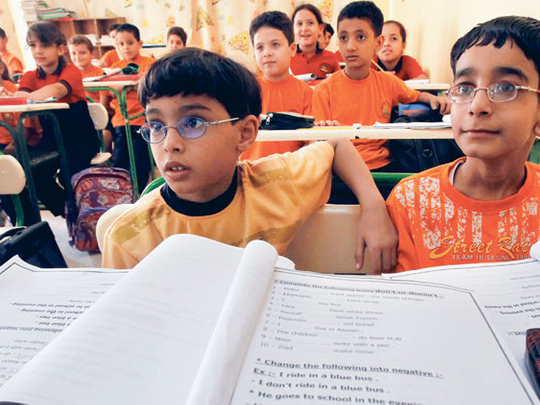

In a class that can accommodate only 20 students, May Mustafa and 60 other students struggle to stay focused. With pale white walls, old wooden desks and a small blackboard topped with the Egyptian flag and President Hosni Mubarak's picture, real education seems a hard task.

May, 15, a student in the tenth grade at the Al Nahda public school in the old district of Ain Shams, prefers to stick to her white-and-navy-blue school uniform and demanding school schedule.

May confessed to Weekend Review that most of her friends started ignoring school rules and neglecting class teachers, as school no longer fulfils students' educational needs. As most take private education, the school's role is limited to just meeting friends.

"Studying seems to follow me everywhere — in mornings at school and at evenings in private lessons," May said, referring to the exploding phenomenon of private lessons that has become a characteristic of almost every household having a student in any of the educational stages from kindergarten to university.

Private tutoring takes place in the afternoons or evenings, on weekends and during the holidays. Most private lessons closely follow the school syllabus, which aims at improving students' performance in examinations.

They are provided for a fee that depends on the subject — science and mathematics cost more. Also, the price of sessions depends on the residential area where the student lives.

According to the Egyptian private-owned newspaper Almasry-alyoum, the cost of private tuitions in maths and the sciences has reached anywhere between 50 and 60 Egyptian pounds (Dh32 and Dh38) per hour. In lower-income residential areas, the prices are between 25 and 30 Egyptian pounds.

"Sending my children to school without having arranged for a tutor is like not getting them their books and clothes," May's dad, who owns a small shop, told Weekend Review, adding that tuitions "consume much of the students' and teachers' spare time and a large part of the average Egyptian family's budget."

Technically, private lessons are banned under Egyptian law. But a recent survey published in Egypt's official newspaper Al Ahram stated that about 66 per cent of schoolchildren get private tutoring, costing Egyptians about 16 billion Egyptian pounds (nearly $3 billion). To manipulate laws, private tuition centres set them up in residential buildings as charitable facilities or video-game venues.

The survey, which was conducted by the Social Research Centre in Egypt, revealed that 39 per cent of families that opt for private tuitions for their children spend more than half the family's income on it. This makes it difficult for families to cope with the burden, especially since nearly 44 per cent of families in Egypt live below poverty index level, according to UN reports.

Across the globe, education receives a great deal of attention, attracting large investments. It is also perceived as a public service that should be provided by the state. However, in Egypt, education is a major aspect of development and the only hope for a brighter future.

Egypt's education system is not only the largest in the Middle East and northern Africa but also one of the largest in the world. With approximately one third of the population under 15, it is regarded as a crucial task and an important investment in the future of the country.

Dr Saeed Esmail, a professor in the Faculty of Education, said Egypt's education system is complex, steered by a centralised system with the government having unlimited control over the decisions of the curriculum, programme development and deployment of staff.

"President Nasser's socialist reforms in the 1950s granted free and equal access to all educational facilities, mainly to increase the base of support for the new rulers. Since then, the government has been responsible for offering free education to all. Compulsory education, which consists of pre-primary, primary and preparatory levels, grants students the basic education-completion certificate," he said.

Education has witnessed several major transformations, though. Before the 19th century, it fell under the control of the religious clergy (Ulama), with most institutes teaching theology. However, village churches and mosques imparted young boys with basic education.

A modern European-style education system was first introduced by Mohammad Ali during the first half of the 19th century; the establishment of secular education, such as schools for accounting, engineering and administration, resulted in the emergence of an educated Egyptian middle class while the lower classes still relied on the traditional Quran schools, called katateeb.

"Education is a right for people as is their right for air and water." It was with these iconic words that Dr Taha Hussain, doyen of Arabic literature, adopted a new system of free education at all pre-university levels, upon his appointment in 1950 as the minister of education.

Although public education is still free in Egypt, former president Anwar Sadat's "Open Door Policy", which encouraged foreign investment, created two levels of education, the public and the private. But due to the steady increase in enrolment rates and lack of financial resources in the past decades, the public education system has been struggling to cope with the rising number of students.

According to the World Bank, the government's expenditure on education in 2007 was 20.4 billion Egyptian pounds, about 12.6 per cent of its budget. Investment in education as a percentage of GDP rose to 4.8 in 2005 but then fell to 3.7 in 2007.

Today, 80 per cent of students are enrolled in primary school and 68 per cent are enrolled in secondary schools. There are approximately 21 million school students in Egypt, of which 18 million are enrolled in government schools and three million in private schools.

Professor Dr Nadia Jamal Al Deen, director of the National Centre for Educational Research and Development, said the chronic problem with education lay in the gap between what students study at schools and universities and the requirements of the market.

A new report by the World Bank and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development urged a reform in the nation's higher education system to ensure responsiveness to the labour-market requirements, as the heavy investments in expanding education did not provide graduates with the necessary skills to compete internationally.

There is further evidence to support this conclusion — it is reflected in the steady increase in the number of fresh graduates who add each year to the growing pool of unemployed youth.

According to the Arab Labour Organisation, Arab nations have among the highest unemployment rates in the world, averaging 14 per cent to 25 per cent. The same report stated that Egypt's announced official jobless rate was 8 per cent but actual unemployment was estimated to be from 15 per cent to 25 per cent.

Nabeel Girgis, a 25-year-old who graduated from the faculty of commerce of the prestigious Cairo University in 2007, said: "After graduation, I found out that most good jobs need additional courses, in computer and English language. I understood that I either had to enrol in such courses or settle for low-wage jobs."

Amira Ezzat found the situation more complicated for girls. Although she had graduated seven years ago, she admitted that private-sector jobs are not suitable for girls — sometimes because of the late-night working hours or the nature of the work itself — such as the job of a salesperson, where one is required one to go around cafes and gatherings to try and sell goods, or stand and present "time share" schemes to customers.

However, analysts believe the most important challenge is the difference in the quality of education received by the rich and the poor, which is also known as the "wealth gap".

While the poor now have to rely on the underfunded and deficient public system, the wealthier families can afford to educate their children in an increasing number of private and "language schools", which have become a prerequisite for getting well-paid jobs later in life.

Today, several types of private high-profile schools exist in Egypt, including international institutes that follow another country's curriculum. There is also the process of earning an official certification from the Ministry of Education to be eligible to enrol in Egyptian universities.

Quality, however, comes at a cost — as such schools charge as low as 5,000 Egyptian pounds and up to 60,000 Egyptian pounds a year.

Monira Salama, 42, mother of two young children enrolled at the American International School, told Weekend Review she is happy that her children have the chance to experience American education in Egypt even if it costs her a fortune.

"Education is the best investment to make in your children's future. Other children in public education are tied to the government's curriculum and that doesn't help develop creativity or scientific thinking. You have to memorise large amounts of information to only pass tests and forget it all after you finish," Salama said.

Many private schools offer additional educational programmes along with the national curriculum, such as American High School Diploma, the British IGCSE system, the French baccalauréat, the German Abitur and International Baccalaureate.

However, Hani Hilal, the Egyptian higher-education minister, denied the existence of such a gap, stating that private education's costs are announced but, unfortunately, that of public education is not.

"It sometimes looks to people like public education or public universities are free. They are not: The costs are completely covered by the government. The government bears all the costs of public education. This is the difference."

Hilal said: "People would unfortunately say: ‘I'm only paying a few pounds at the beginning of the year and this is the cost of education.' This is not the cost of education; it's the concept of the culture of the people rather than the cost itself. No service comes for free."

The second major challenge that Egypt faces is the shortage of teachers. This problem is precarious in rural areas. There is a common conception that teaching is of low prestige. Young people choose this career only when there is no other option or when it serves as a stepping stone to the more lucrative career of private tuitions.

Although last year Mubarak implemented the new "Teachers Cadre's Law" to increase salaries, they remain comparatively low. Also, many Egyptian teachers have travelled to other Arab countries, where conditions may be considerably better. Through the 1980s, some 30,000 teachers left Egypt every year.

Low pay has always been a common complaint among the teaching staff. Ali Al Kady, a 36-year-old maths teacher, told Weekend Review that given the low wages they get, private lessons seem to be the only after-school activity suitable for teachers.

"After years of calling for a serious reassessment of our salaries, the ministry agreed to raise it by a few hundred pounds but with the condition of taking an assessment exam to determine whether or not we are eligible for the raise. Most teachers protested, boycotted the exam and considered it an insult," Al Kady said.

People are still optimistic that the political will in Egypt will envisage education as the cornerstone and the key for both the country and its citizens, believing what President Mubarak said: "Education and its progress is our path and gate to the New World map. Education is the cornerstone of our nation and our only way to local and international competition."

- Raghda El Halawany is a journalist based in Cairo.