Is India witnessing a tectonic shift of power in favour of the underclass? Going by expert opinion expressed at a round table discussion at the Indian Embassy in Abu Dhabi on Wednesday, a conclusion to this effect seems inevitable.

As Indian Ambassador to the UAE Talmiz Ahmad pointed out at the outset, there was an increasing rejection of the present political system in India with an assertion of the underclass that was seeking to be represented in its own right.

As author of the title of the discussion “Revolt of the Underclass: India at the Crossroads on the Eve of General Elections'', Ahmad defined the underclass as a disadvantaged, marginalised section that is not part of the power structure but not necessarily a part of the poverty syndrome. At another level, he referred to a new underclass that had spoken out against the political system post 26/11 when terrorists struck in the city of Mumbai.

Saeed Naqvi, political commentator and chairperson of the round table, was unequivocal when he said the days of the national charismatic leader were gone with regional parties being the order of the day. According to him, communalism and caste politics had played themselves out and were not paying off.

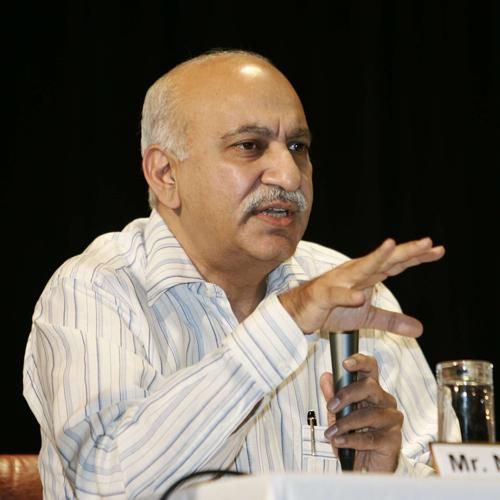

Asking if poverty was the political identity of India, MJ Akbar, senior journalist from India, regretted that the poor were being mobilised along parallel identities, mainly along religious and political lines.

The concept of the majority and minority was a function of empowerment, not numbers, he noted. Citing from a survey conducted in Agra of Uttar Pradesh, he spoke of how 75 per cent of Dalits in the city used to live off selling animal skin in 1991 but this number had now dropped to one per cent.

“This is when empowerment delivers,'' he said, later alluding to the Indian electorate as the “greatest jury in civilisation''.

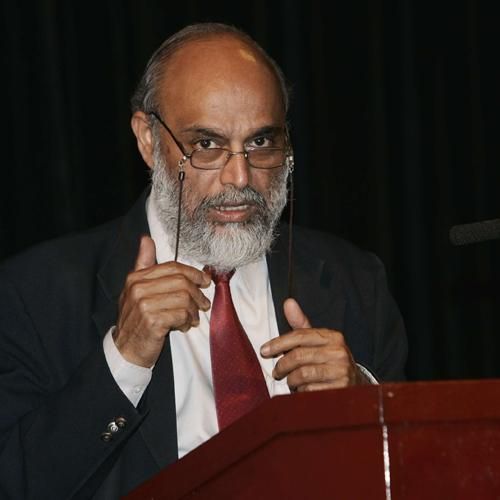

Professor Mushirul Hassan, Vice-Chancellor of Jamia Milia Islamia University in New Delhi, dwelt on the “grim Muslim scenario'' in the country. “I believe that Indian society is moving towards being insensitive to minority rights and interests,''

He said the basic problem lay in the image of Muslims which needs to be changed.

Among the other corrective steps he mooted were a discussion, not dismissal, of the Muslim reservation issue and state intervention in areas like education for girls.

Getting back to the issue of regional parties, Dirender Ojha, an Indian Information Service officer and journalist from India, spoke on the empowerment of the disadvantaged sections of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in Uttar Pradesh and traced the growth of regional political parties like the Bahujan Samaj Party and Samajwadi Party.

The reasons for the social change in the state, as he saw it, lay in “the weakening position of landlords, economic growth, rise in literacy, area-based development programmes and symbolic actions'' by leaders like Mayawati, the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh.

Atul Aneja, the correspondent of Indian daily The Hindu in Dubai, who attempted to locate the underclass in India, said the revolt of the underclass, the peasantry, had to succeed to overcome the distress in agriculture which was being manifested both in terms of physical and food security.

The last but most vocal speaker on the panel was political and security analyst Commodore C. Uday Bhaskar from India who looked at the relevance of the southern states in national politics and how cinema was a factor to contend with in state politics. Noting that the four southern states – Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Kerala – had less than a 25 per cent share in Parliament, he wondered if they could “swing'' equations at the Centre.

The round table was followed by a reception hosted by the Ambassador at the India House lawns.