Dubai: Over dinner in his room, Ayoub Khan and his friends are having a heated discussion on the increasing cost of living and the stagnant salary structure.

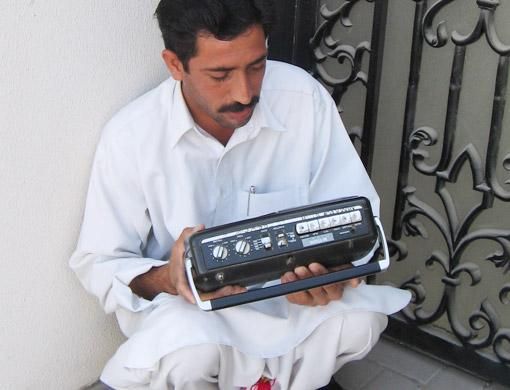

As his friends continue talking after dinner, Ayoub quietly slips out of his room with a small cassette recorder. Huddled up on the roof of his ramshackle house in Satwa, the illiterate construction worker pours out his heart to the rusty equipment that screeches as the cassette soaks up every single word he utters, without missing the accompanying emotions.

The 28-year-old has explained to his ailing father why he could not send money last month, has asked his mother whether she is taking her medicines regularly, has assured them that he will come home soon and get married and so on.

It is a full 45-minute conversation with his loved ones. The cassette is now ready to be shipped to Peshawar, where Ayoub's family lives, through a friend leaving for Pakistan next week. Ayoub is, however, not sure when he will receive a reply, again through a cassette.

Despite the technological revolution that has brought internet and mobile phones within the reach of all, many like Ayoub still prefer to use recorded tapes for communication. The reasons vary from both financial to personal.

"It has become a habit for me and my family. When you are on the phone, how much can you talk?" says Ayoub, toying with his mobile phone.

He also prefers it to telephonic conversation because "I can listen to it over and over again, whenever I want," he says.

Writing letters has never been a communication option for thousands of illiterate workers in the UAE.

"Ever since I came to Dubai seven years ago, I have been using this [cassette player] to talk to my wife and children and hear their voices. I have started making calls in the last few years, but there is nothing more comforting than listening to my wife's voice on a cassette player," says Mohammad Hussain, a Bangladeshi worker.

He said he buys dozens of cassettes cheap from his country and uses them for months.

"The only problem is that you do not get an instant response as you do when you talk on the phone. But these days it is not difficult to send and receive a cassette," said Mohammad, who saves around Dh150 on telephone cards.

But many workers told Gulf News that it is a dying practice as most of them have moved on to mobile phones. "There are only a few people who use the cassette recorder," said Mohammad Ebrahim, a worker from Pakistan, who lives in Jaffliya.

He added that he had a collection of over two dozen cassettes from his parents and wife until a year ago. "I took them all home when I went to Pakistan last year. Now, they also have mobile phones."

His friend Zaman Khan says it is okay to spend Dh150 to Dh200 on phone calls in a month. "Now that mobile calls are cheaper, we do not have the patience to sit and record our voices and courier the tape back home. I have used cassettes for over four years. But now I make calls once a week," said Zaman.

Similar sentiments are echoed by Badshah, from Tamil Nadu, India, who works in a cafeteria in Jaffliya. "When I first came to Dubai, mobile phones were so expensive. I did not know how to use a phone card so I used a cassette."

Now, things are changing as illiterate workers understand technology and its benefits better.

How often do you communicate with your family back home? Do you have a creative way of contacting them? Have you cut down on international calls owing to the economic crisis?